The Early Years

In the early months of 1830, during what were to be the last six months of the reign of King George IV, printers William Bradbury and Frederick Mullett Evans established their first printing office together at 1 Bouverie Street, Whitefriars, London. This is a fairly slender street, situated in a gap between numbers 62 and 63 Fleet Street in the Whitefriars district of London; they were to settle at number one for two years before moving a little further along the same street to number twenty-two. [1] The year before Bradbury and Evans' arrival the literary critic and essayist William Hazlitt (1778-1830) had rented rooms on the first floor of a house at number three. An early description of the street read:"A very substantial improvement has however taken place in this precinct, most of the ruinous places have been levelled, and an avenue, rather narrow, composed of stately houses, into Fleet Street, denominated Bouverie Street, has risen in their room." [2]

William Bradbury, the senior partner, was a printer to his core. At the age of fourteen he had served a seven year apprenticeship in Lincoln, Lincolnshire, under the master printer John Drury, and had run his own printing offices since 1821. Frederick Mullett Evans was a native Londoner. After serving an apprenticeship in Bath, Somerset he worked for the publishing firm of Hurst, Chance and Co at 65 St Paul's Churchyard, London when Edward Moxon (1801-1858) joined that firm as a Literary Adviser. The two were to become lifelong friends. [3] Evans also had a brief partnership in the summer of 1829 with a gentleman named Francis Joyce, one of the brothers of Felix Joyce who became Bradbury and Evans' Chief Accountant/Manager. In July 1829 the two men, operating under the partnership of 'Joyce and Evans', took over the running of a circulating library on the High Street in Southampton following the retirement of the previous owner due to ill health. As well as this substantial library, Joyce and Evans offered the public book-binding facilities, engraving and printing. [4] However this venture between Francis Joyce and Frederick Mullett Evans was to be extremely short-lived with their partnership dissolving on 1 September 1829. [5] Joyce married the following month and remained in Southampton running the circulating library with his wife for a few years, before declaring bankruptcy and disappearing to France with a lover in 1837! [6] Evans meanwhile returned to London, entering in to partnership with William Bradbury a few months later.

At this early stage in their careers, both Bradbury and Evans lived within a short distance of their work. Bradbury, his wife Sarah (nee Price) and their young family moved approximately one mile from their previous residence in the newly built Wingrove Place, Clerkenwell, to 22 Bouverie Street, presumably in order to be at the heart of the business.

View of part of Stamford Street, Lambeth, London looking West, taken in August 2015. Frederick Mullett Evans and his wife Maria lived on this street for a time in the 1830s.

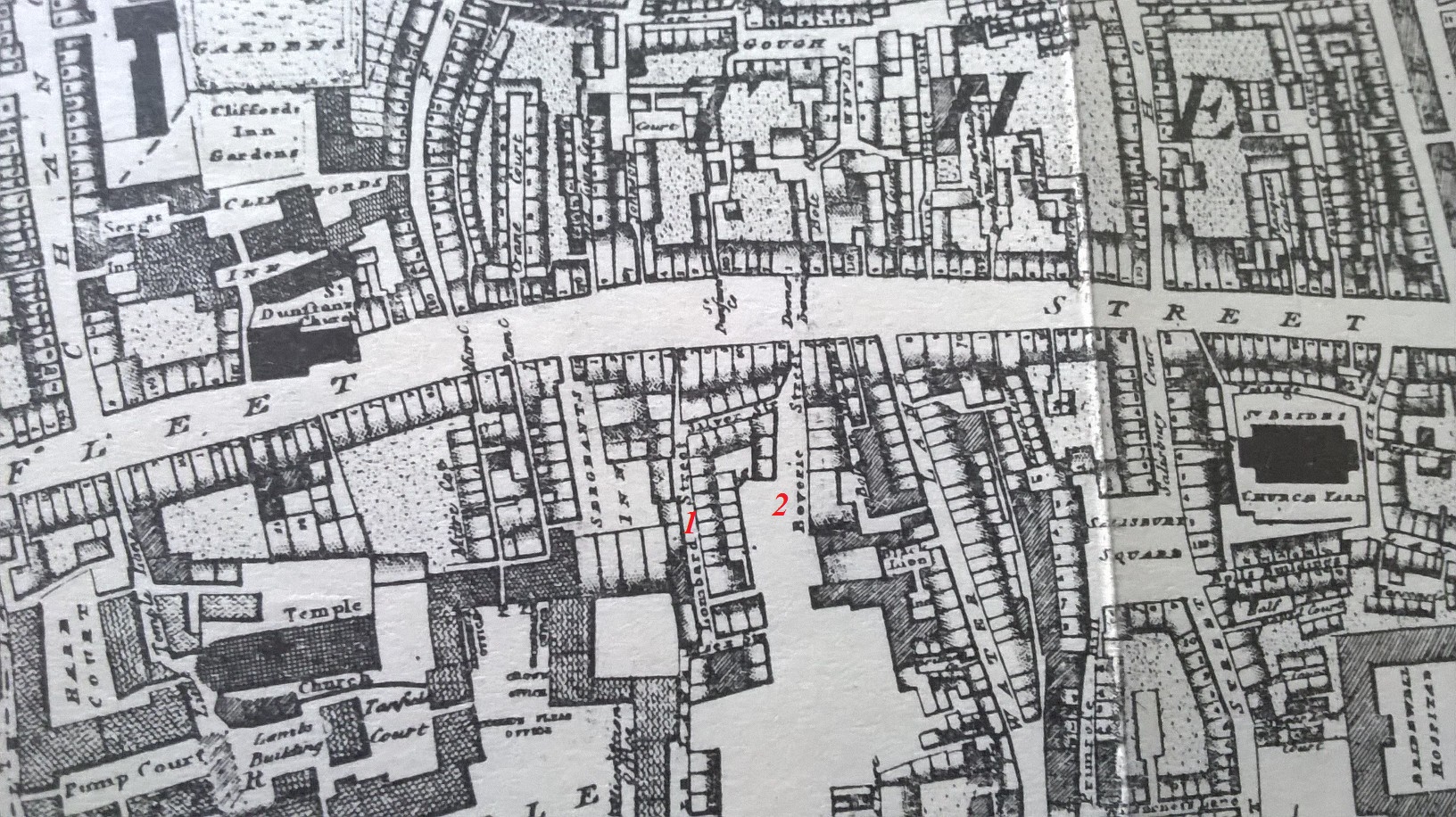

Click to enlarge. Detail from Richard Horwood's 1799 Map of London with Lombard Street and Bouverie Street marked by red numbers.

In 1833, as the business grew, Bradbury and Evans also took over vacant premises in an adjacent street, Lombard Street (now Lombard Lane), which had been occupied for over thirty years by the highly respected printer Thomas Davison. The building was on the site of the George Tavern, on what was previously known as Dogwell Court, a tiny lane joining Bouverie Street and Lombard Street. Davison, being particularly noted for his skill in the manufacture and drying of inks, had printed for most of the leading London publishers of the day. These included Taylor and Hessey and John Murray of 50 Albemale Street, for whom he printed all of the Byron editions and Jane Austen's Persuasion. Following Davison's death on 30 December 1830, the printing office had been run by his son George Kearsley Davison, and Thomas' two friends, John Simmons and William Wilcockson, until April 1833 when they dissolved their business partnership. George Davison continued to work in Lombard Street as a maker of printing ink, taking an office next door to Bradbury and Evans.

Lombard Street, as so many London streets, was a cramped, crowded, bustling mix of business and residential premises, with families renting rooms above business establishments. Two such families were James Mansell, a tailor, his wife Margaret and their three children and John Jones, his wife and seven young children who had rooms opposite Bradbury and Evans' establishment, above the premises of Benjamin Slee, a cabinet maker. Bradbury and Evans were using seven adjacent rooms in the building as a paper store. Benjamin Slee’s stock room, packed full of his hand-crafted items such as dressing cases and work boxes, was located on the second floor above the Jones family. In the early hours of Sunday 24 November 1839, the Mansell and Jones families were sleeping. The Jones’ were struggling through a particularly difficult time; Mrs Jones had just the week before given birth to twins, whilst her husband was so ill that he was unable to work having been bedridden for the previous six weeks. At about 1.30am the two families awoke to a living nightmare; fire had broken out in Benjamin Slee’s stock room. Due to the dry and combustible nature of the stored goods the fire spread rapidly through the building from room to room, gathering momentum as it went. Before long the entire upper floor was ablaze. Windows cracked and exploded due to the intense heat, sending flames rolling out across the narrow street and into Bradbury and Evans’ premises. The families were awoken by the crackling and roar of the flames; horrifically by the time they awoke the entire ceiling in the Jones’ apartment was alight, causing part of it to break off and crash down on to Mrs Jones’ bed. In fear for their lives and with no time at all to gather anything but themselves and their children, the Mansells and Jones’ fled the flames and the suffocating smoke in just their nightclothes. Thankfully they all made it out of the burning building alive; gathered in the street they huddled together to watch in horror as everything they owned in the world was destroyed. Nearby police constables summoned fire engines, and within a short time several engines were at the scene, led by James Braidwood, Chief Officer of the London Fire Engine Establishment, which was later to become the London Fire Brigade. There then, however, followed a twenty minute delay as there was no water immediately available in the street and so all the fire brigade, residents and passers by could do was to watch helplessly as the fire raged. Eventually the water supply was drawn and the fire was brought under control. Bradbury and Evans' premises were saved from destruction, although their paper supplies were extensively damaged. However the homes of the Mansell and Jones families, were completely destroyed. Mr Slee was fortunately insured against fire, but the two families had lost everything. An appeal was organised by Bradbury and Evans to raise money for the destitute families, with donations being received by Foreman Charles Hicks at their premises in Lombard Street.

During these early years of Bradbury and Evans' partnership the country was deeply mired in economic crisis; by the autumn of 1831 over six-hundred London printers found themselves out of work. As noted in the section on Bradbury and Dent the crash of the London Stock Market in April 1825 had led to the closure of some high-profile London banks, and by the end of that year a financial panic had gripped the country. Recession followed leading to bankruptcy and business failures; the printing and publishing industries were hit particularly hard. However, a large part of Bradbury and Evans' success was down to their keen business sense, and the fact that they were enthusiastic adopters of new, modern technology; at an early stage they installed into the Lombard Street premises an enormous, state of the art, steam driven cylinder-press. This was followed in April 1835 by an announcement in The Monthly Literary Advertiser:

"Bradbury and Evans (late T. Davison) beg to inform the Trade that they have added a STEREOTYPE FOUNDERY (sic) to their PRINTING ESTABLISHMENT, and that they shall be happy to execute all works entrusted to them with care and expedition."

They were thus enabled to vastly increase their production speeds of journals and periodicals. Before long the Lombard Street presses would be running day and night.

George Cruikshank's Illustration Salus Populi Suprema Lex showing John Edwards, owner of the Southwark Water Company, and the filthy state of the River Thames near London Bridge. Published by S. Knight 1832. Public Domain via Creative Commons Licence for educational and non-commercial purposes.

Not only was the country suffering an economic crisis at this time, a public health crisis loomed dangerously large in the form of cholera. Caused by ingesting water contaminated with faeces, this deadly bacterial infection arrived in Sunderland in the North East of England in October 1831 and had spread as far as Scotland and London by early 1832. Death could occur with extreme rapidity from cholera; a newspaper report in July 1832 stated that the Hon. Mrs Smith, sister of Lord Forester and daughter-in-law of Lord Carrington, had died from cholera at her home in Belgrave Street, London, in just eleven hours following a visit to the opera. [7] At that time the connection had not been made between the state of the water that the public drank, bathed and washed in and the cause of cholera. The River Thames, which ran only about two-hundred metres away from Bradbury and Evans' premises at Bouverie and Lombard streets, was absolutely filthy; human and animal excrement and all manner of industrial waste and household rubbish washed straight into the river. This water was then used and drunk by the population without the water companies undertaking any treatment to clean and purify it. The extremely unpleasant state of the water supply had been discussed in parliament and amongst the medical profession for years. In July 1828 a commons sitting in Parliament heard that drinking water from the Grand Junction Waterworks Company, which supplied areas of West London, had been examined and found to contain " much deleterious matter dissolved in the fluid, as well as a considerable quantity of indissoluble matter suspended in it." [8] However awful the water supply was though, it was to be another twenty-two years before the link was finally made between contaminated water and cholera. In the 1830s it was chiefly suspected that cholera was caused by a 'miasma', or poisoned air, that disease was contained in bad smells. Thirty-two thousand people in Britain died in the 1832 epidemic, and during Bradbury and Evans' working lives in London there would be further outbreaks of cholera in every decade.

Early Printing Relationships

Frederick Mullett Evans was a particularly genial and warm individual, forming close and easy friendships. This sociability brought Bradbury and Evans valuable printing work in the spring of 1830 just as they were starting their new business partnership. Frederick Mullett Evans' close friend, the poet and Literary Adviser, Edward Moxon was establishing himself as a publisher in his own right, taking on premises at 64 New Bond Street, London. The first publication that he published from his Bond Street premises was a book titled Album Verses written by his good friend the poet Charles Lamb. Moxon chose as the printers for this book his friends Bradbury and Evans. [9] Moxon also developed a close friendship and publishing relationship with Alfred 'Lord' Tennyson, first publishing the then twenty-three year old Lincolnshire poet's work, a work which included 'The Lady of Shalott', in a book simply titled Poems in December 1832 (the title page is dated 1833). Again Bradbury and Evans were approached to undertake the printing. They printed a short-lived monthly magazine of Moxon's titled The Englishman's Magazine which ran for several months during 1831 to which both Lamb and Tennyson were contributors. Amongst many other works for Moxon they printed English Songs and Other Small Poems written by Barry Cornwall, the pseudonym of Bryan Waller Proctor, a poet friend of Charles Lamb and Douglas Jerrold in 1832, and also works for the poets Wordsworth and Shelley. In fact according to Edward Moxon's biographer Harold G Merriam Bradbury and Evans carried out the printing for all of Moxon's publications bar one. Over the period 1840-1842 Bradbury and Evans' work for Moxon brought them in receipts of £6,810 [10] Their early work for Moxon helped to establish them as a reliable and trusted firm. In a letter dated 23 March 1843 William Wordsworth wrote to Moxon praising the "care and attention of Messrs Bradbury and Evans". The friendship and business relationship that they developed with Edward Moxon lasted until his untimely death on 3 June 1858. Following his death, and in accordance with his wishes, Frederick Mullett Evans became Manager of Moxon's business, and the publishing house imprint became Edward Moxon & Co.

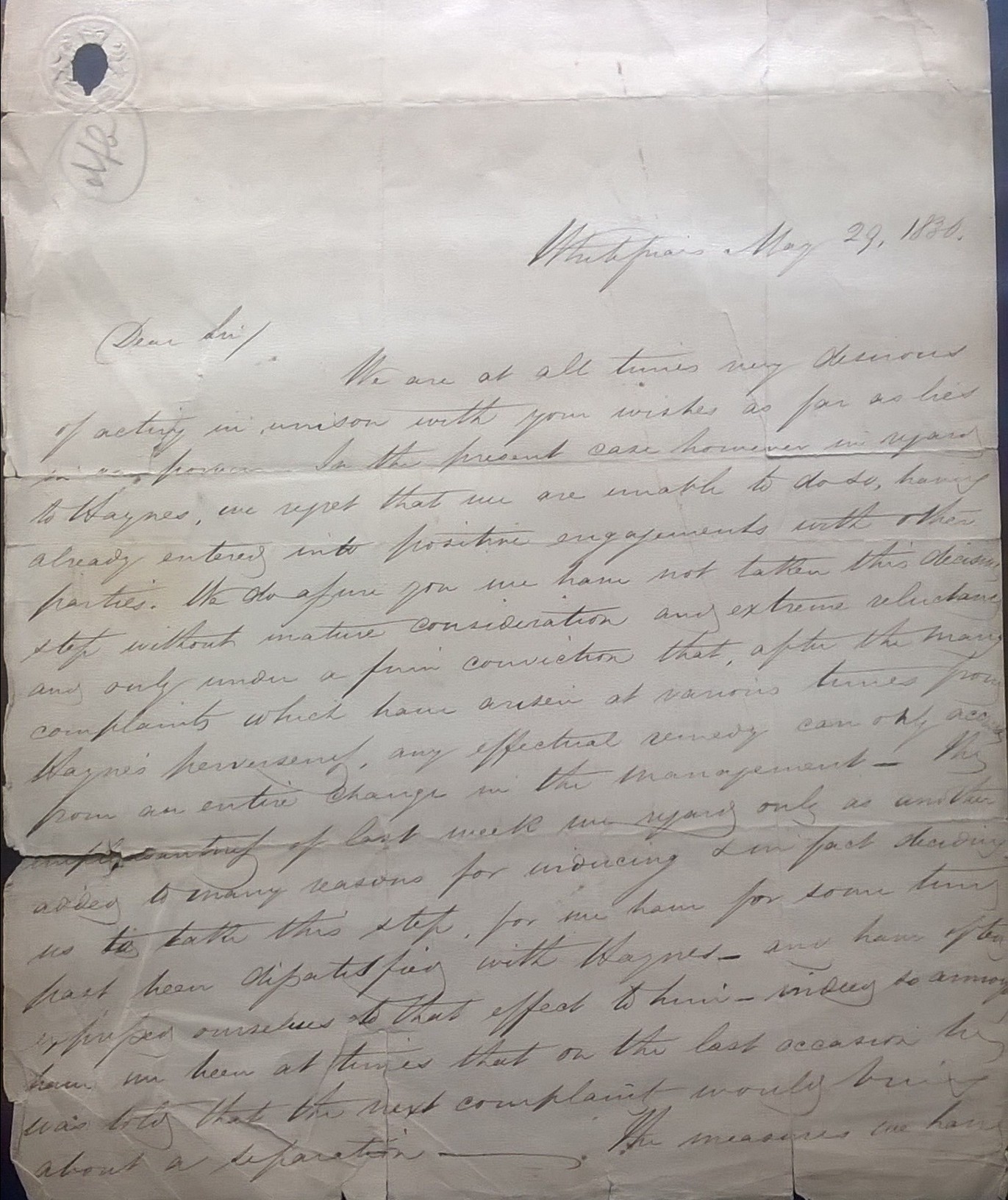

Letter from Bradbury and Evans, Whitefriars, dated May 29 1830 to Sir John Philippart. Authors own collection

Reverse of letter from Bradbury and Evans, Whitefriars, dated May 29 1830 to Sir John Philippart. Authors own collection

At the end of May 1830 Bradbury and Evans were undertaking work for the military writer Sir John Philippart (c1784-1874). As the following transcript of a letter dated May 29 1830 from Bradbury and Evans to Sir John indicates, the young partners did not shy away from taking firm and decisive business decisions; their reputation was clearly of the utmost importance to them. I feel we can deduce from the letter that Sir John Philippart had previously contacted Bradbury and Evans to ask for leniency in the dismissal of a Mr Haynes from the management of the work for Sir John. They were known to be liberal and supportive employers, and the sentiments of the postscript are an interesting juxtaposition to the main body of the letter:

"Dear Sir, We are at all times very desirous of acting in unison with your wishes as far as lies in our power - In the present case however in regard to Haynes, we regret that we are unable to do so, having already entered into positive engagements with other parties. We do assure you we have not taken this decisive step without mature consideration and extreme reluctance and only under a conviction that, after the many complaints which have arisen at various times from Haynes' perversity, any effectual remedy can only ?accord? from an entire change in the management - The unpleasantness of last week we regard only as another added to so many reasons for inducing & in fact deciding us to take this step, for we have for some time past been dissatisfied with Haynes - and have often expressed ourselves to that effect to him - indeed so annoyed have we been at times that on the last occasion he was told that the next complaint would bring about a separation - The measures we have now made we have no doubt will be equally beneficial to yourself as to us, inasmuch as vexatious complaints will the more likely be prevented and a better confidence thereby engendered - a matter of essential importance to the interests & well doing of the Paper, and also to our comfort & satisfaction so long as we have the responsibility of printing it-(signature etc)(postscript) PS Haynes knows full well that we have not a shade of ill feeling towards him - & though for the reasons stated he will cease to have the management of the Paper, yet we have not the slightest objection to give him other employment - if he thinks proper."

This letter offers a tantalising glimpse into a particular incident, I would love to know what "The unpleasantness of last week..." was!

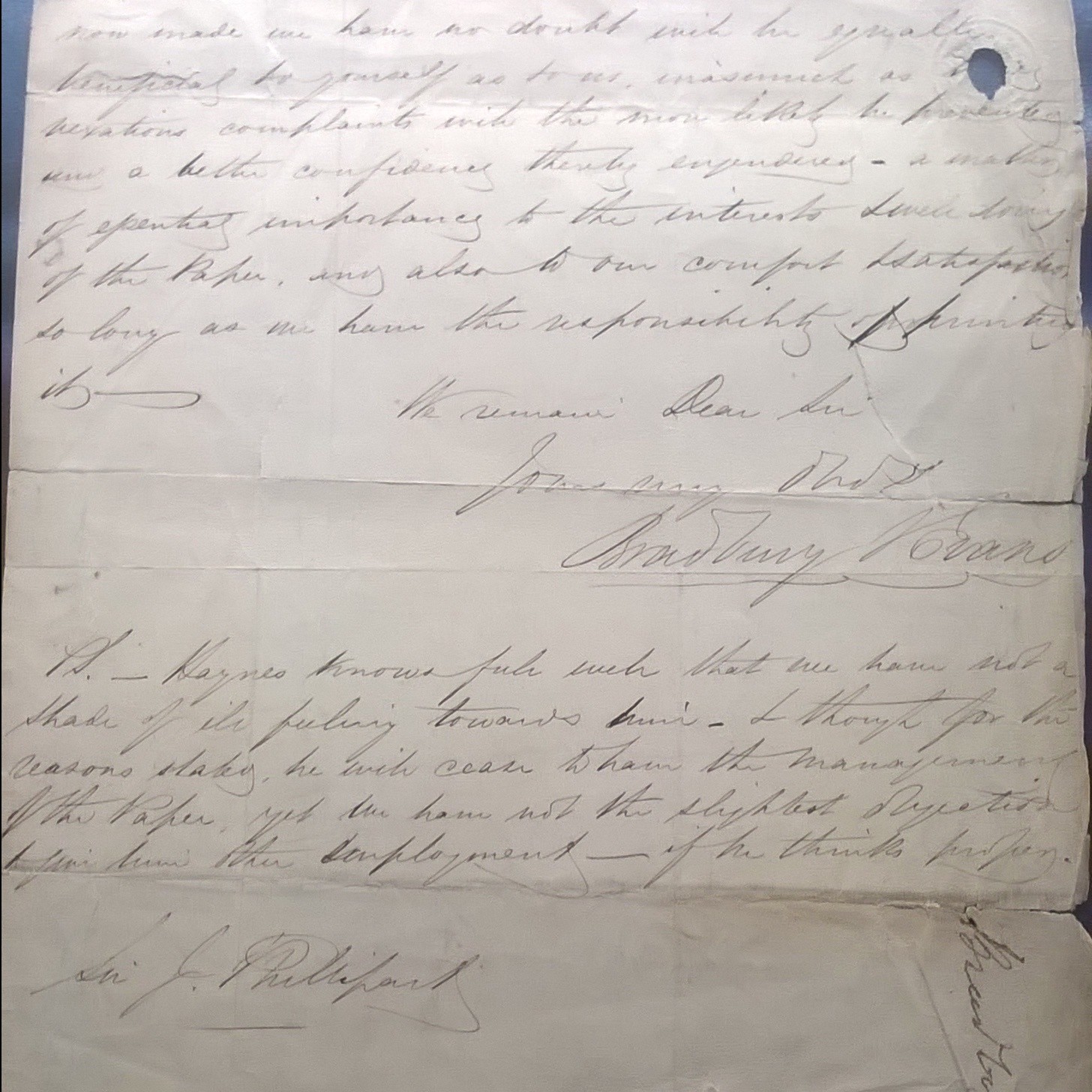

William Somerville Orr was a Scottish publisher and bookseller who in his early thirties had premises alongside St Paul's Cathedral at 14 Paternoster Row, London. From 1833 until 1836 Orr was in partnership with William Smith, under the publishers imprint of Orr and Smith. In 1834 he added premises a short distance away from Paternoster Row at 2-3 Amen Corner, St. Paul's, London.

James Rennie's Alphabet of Botany, published by Orr and Smith, Paternoster Row, printed by Bradbury and Evans, Whitefriars 1834. Authors own collection.

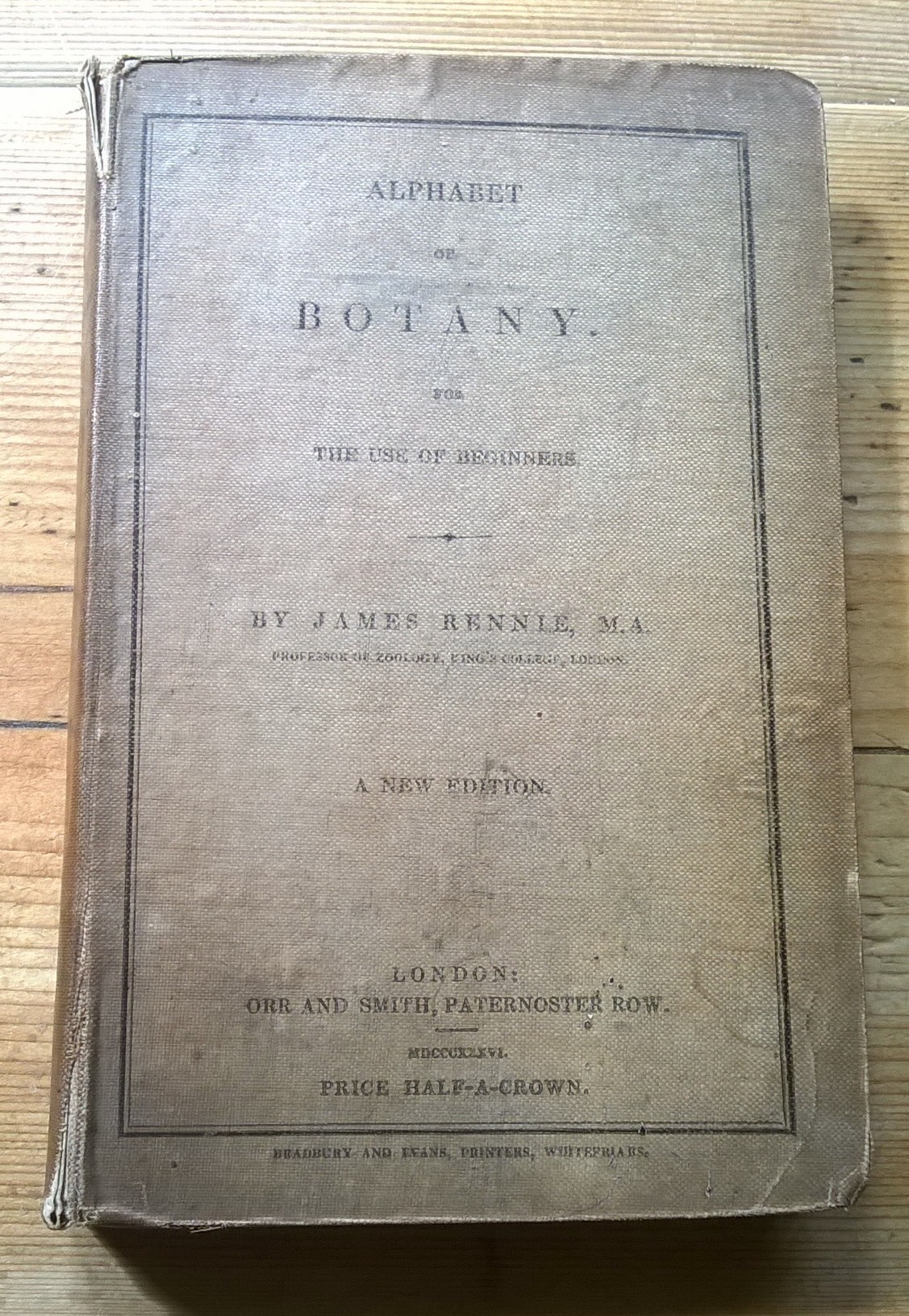

Chambers' Edinburgh Journal published by William Somerville Orr and printed by Bradbury and Evans. Authors own collection.

Chambers' Edinburgh Journal published by William Somerville Orr and printed by Bradbury and Evans. Authors own collection.

Orr was friendly with William and Robert Chambers, the Edinburgh based publishers who were particularly noted for their weekly magazine the Edinburgh Journal. In April 1832 Orr entered into an agreement with them to produce their Journal in London. The Chambers brothers stipulated that this London version of the Edinburgh Journal had to look as similar as possible to the Edinburgh issue and must be identical in its content. [11] To this end they had stereotype plates, which had been made by A Kirkwood, sent weekly from Edinburgh for the printing process. In order to produce this London version of Chambers' Edinburgh Journal, Orr at first used the printing firm of John Haddon and Co on Ivy Lane, London but soon turned to Bradbury and Evans. The Journal was a great commercial success, and Bradbury and Evans continued printing many of the works that Orr published. Another of Orr's clients was the Garden Designer and Architect Joseph Paxton (1803-1865). Paxton, Head Gardener for the Sixth Duke of Devonshire at Chatsworth House, and future architect of the Crystal Palace, would become one of Bradbury's dearest friends. In the 1840s, when Bradbury and Evans were the proprietors of Punch magazine, Paxton would be one of the select few non-staff attendees at the Wednesday night Punch dinners. Bradbury and Evans printed Paxton's various works, works which included the Horticultural Register, his Magazine of Botany and Register of Flowering Plants, and his Pocket Botanical Dictionary.

During these early years they also undertook work for the author, poet and humourist Thomas Hood (1799-1845). In 1829 Hood produced his first Comic Annual, published towards the end of 1829 by Hurst, Chance and Co. The title page carried the date of 1830 and the printers imprint showed Bradbury and Dent, Oxford Arms Passage. As Bradbury and Dent ended their partnership on 31 December 1829 the printing of the Comic Annual was probably one of the last projects they undertook together. The Comic Annual was somewhat of a forerunner to Punch magazine in that events of public interest were satirised, punned about and caricatured vigorously but without vulgarity. Hood changed publishers twice over the eleven volumes of the Comic Annual that were produced, but Bradbury and Evans retained the printing contract. In December 1843 Thomas Hood sent Mark Lemon, the editor of Punch magazine, his poem The Song of the Shirt. Bradbury and Evans had been the printers and proprietors of Punch since December 1842. Despite the fact that the poem had been rejected by three publishers previously, Lemon decided to accept it and the poem was published in Punch on 16 December 1843 anonymously. Focusing on the life of a seamstress living and working in abject poverty, the poem became something of a sensation drawing attention to the dire circumstances of the working poor in Victorian England, and as a consequence of the publicity also succeeded in raising the profile of Punch magazine tremendously, with of course the associated increase in the profile and profitability of Bradbury and Evans.

Arguably the most important early connection for Bradbury and Evans' fledgling business came with their work for the publishing house of Chapman and Hall, publishers for the author Charles Dickens. This early relationship led to them becoming publishers themselves when Dickens chose them to be his new publishers following a major falling out with Chapman and Hall in 1844.

References

- ^ A Directory of Printers and Others in Allied Trades London and Vicinity 1800-1840 (1972) William B Todd

- ^ London; Being an Accurate History and Description of the British ..., Volume 4 (1807) David Hughson

- ^ Edward Moxon Publisher of Poets (1939) Harold G Merriam page 11

- ^ Hampshire Telegraph and Sussex Chronicle Monday 6 July 1829

- ^ The London Gazette 1829 page 336

- ^ Morning Advertiser 8 June 1865

- ^ Staffordshire Advertiser 28 July 1832

- ^ Supply of Water to the Metropolis HC Deb 01 July 1828 vol 19 cc1588-97

- ^ Edward Moxon Publisher of Poets (1939) Harold G Merriam page 25

- ^ Edward Moxon Publisher of Poets (1939) Harold G Merriam footnote page 137

- ^ see essay William Somerville Orr, London Publisher and Printer: The Skeleton in W and R Chambers's Closet Sondra Miley Cooney in the book Worlds of Print Diversity in the Book Trade Edited by John Hinks and Catherine Armstrong