Frederick Mullett Evans

Family Overview

- Mother: Mary Anne Mullett (1776-1857)

- Father: Joseph Jeffries Evans (1768-1812)

- Wife: Maria Moule 1807-1850

- Children: Sarah Moule Evans (1831-1832); Frederick Moule Evans (1832-1902); Thomas Mullett Evans (1834-1872); George Moule Evans (1836-1891); Margaret Moule Evans (1837-1909); Joseph Jeffries Evans (1839-1840); Elizabeth Matilda Moule Evans (1840-1907); Horace Moule Evans (1841-1923); Mary Josephine Jedidiah Evans (1843-1845); Frances Joan Moule Evans (1845-1846); Lewis Moule Evans (1846-1878); Gertrude Moule Evans (1847-1919)

Editorial Note:

Much of this page references the family chronicle written by Frederick Mullett Evans' sister Jane Family chronicle of the descendants of T. Evans, of Brecon, from 1678-1857 published in Bristol 1870-71.Family History

Sunday 29 January 1804 was a day so "uncommonly mild weatherwise" in London that Hyde Park was filled with young ladies, who, having cast off their winter vestments, wore "dresses white as the driven snow" decorated with real roses. Approximately five miles away, at her home in Staining Lane, close to St. Paul's Cathedral, London, Mary Anne Evans gave birth to her fourth child, assisted by midwife Sarah Jenkins and sister-in-law Sarah Jeffries Evans (1765-1845). This child, a boy, was Frederick Mullett 'Pater' Evans. In adulthood he co-founded the printing and publishing house of Bradbury and Evans with William Bradbury; a partnership which was to last for thirty-five years.

Frederick Mullett Evans was born into rather an interesting family. His extended paternal family were extremely prominent Baptist Ministers based in Bristol, Gloucestershire. His grandfather, Dr Caleb Evans (1737-1791) and his great grandfather Rev Hugh Evans (1712-1781) were co-pastors at the Broadmead Baptist Chapel in Bristol, working together for some twenty-two years. They jointly ran the Bristol Baptist Academy, which had been set up specifically to train and guide ministerial candidates. His parents, Joseph Jeffries Evans (1768-1812) and Mary Anne Mullet (1776-1857), were cousins; both were born in Bristol and at the time of Frederick's birth, had been married for eight years. They had married at the church of St Botolph without Bishopsgate, London on 23 February 1796 and had needed the permission of Mary Anne's father, Thomas Mullett (1745-1814), as Mary Anne was only nineteen years old at the time and classed as a minor. [1]

Frederick, his sisters Jane (1797-1876) and Mary (1801-1877) and brother Thomas (1799-1834) initially lived with their parents at 16 Staining Lane, London. Remembered by Mary as a large and pleasant house, [2] this spacious property consisted of two dwelling houses which had been knocked into one, forming "a commodious brick dwelling house", above extensive front offices and workshops on the west side of Staining Lane. [3] Having bought his Freedom of the City of London for 46s 8d on 29 September 1797, [4] Joseph worked from these offices trading with his partner Lemuel Thomas (1761-1825) as Messrs Thomas and Evans, Jewellery Merchants and Hardwaremen. [5] In the 1790s they leased an apartment in the house to John Brogden (1774-1832), a manufacturing goldsmith who sold his jewellery to Thomas and Evans for them to resell. [6] Interestingly John Brogden's nephew, also John Brogden (1820-1884), continued in the family jewellery business. He became an extremely notable jeweller, goldsmith and silversmith and examples of his work can be seen in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Joseph Jeffries Evans and Lemuel Thomas were in business together until the autumn of 1808 when their partnership ended by mutual consent. [7]

During his first four years of life Frederick was joined by two more siblings; Robert (1806-1846) and Hugh (1808-1868) and the family moved from Staining Lane to a "spacious roomy residence" at 31 Old Bethlem, Broad Street, London. [8] This rather grand sounding property had two drawing rooms separated from each other by folding doors and also a breakfast room on the first floor. The ground floor, with a "handsome paved entrance hall", had a dining parlour, a large mahogany balustraded staircase, offices and a w.c. Situated approximately half a mile from Staining Lane, the house stood on what is now Liverpool Street, London. From this property Frederick's father Joseph continued in business as a merchant in partnership with his father-in-law Thomas Mullett, to whom he was very close, trading together as Messrs Thomas Mullett and Co.

Early Life

Frederick Mullett Evans and his siblings appear to have spent their formative years happily, living in comfortable surroundings with loving parents and a close extended family who enjoyed the company of literary figures. The Evans' were friends with the poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge and his wife Sara, and also with Henry Crabb Robinson (1775-1867) who was a particularly close friend of Joseph. [9] Robinson described the extended Evans family thus "as affectionate a knot of worthy people as I ever saw." [10] Whilst they were still very young Frederick and his older brother Thomas were sent to be educated at the boarding school of their great uncle Hugh Foskett Evans (1755-1815) in the town of Melksham, Wiltshire. The oldest two daughters, Jane and Mary, were educated at a "seminary for young ladies" about four miles away from home in Denmark Hill, London. The seminary was run by their father's widowed cousin Sarah Evans Biggs (nee Norton) (1768-1834) "a woman of decidedly superior intellectual powers, which it was her delight to cultivate." [11] Due to childhood health issues Jane was unable to attend school until she was ten years old; she was to suffer from quite debilitating health problems for the whole of her life. Each summer the Evans family would leave the hustle and bustle of London behind them and head for their "blessed retreat", a house in Shards Place, Peckham which they rented annually for a small sum. In 1814 Peckham was described as "a hamlet in the parish of Camberwell on the road proceeding to Greenwich." [12] Around this same time Thomas Mullett moved to a house in Clapham, which apparently had a wonderful garden and a field that housed chickens, a cow and a pony. Naturally this house became a huge favourite with the Evans children.

In 1810 when Frederick was just six years old his father became unwell with a suspected liver complaint. Nevertheless family life had to continue despite illness; the Evans' moved approximately half a mile to a house in St Mary Axe, and their last child, a son Charles (1811-1852), was born the following year. However Joseph continued to decline health-wise and Mary Anne found herself devoting more and more of her time to her husband's care. In 1812 it was suggested that he should visit Cheltenham, Gloucestershire to see if a cure or some relief of his condition could be found in the local mineral waters. Joseph, Mary Anne and one of the family servants duly left London to spend several months in Cheltenham, with Thomas and Frederick joining their parents during the school summer holidays. Joseph's unmarried sister Sarah, known to the family as Sally, remained in London taking care of the other children. Jane and Mary returned to school after the holidays and Jane poignantly remembered herself desperately longing for letters from their mother, whilst simultaneously dreading reading their contents. There did appear to be a slight improvement in Joseph's health and he and Mary Anne returned to London in November 1812. Sadly a lasting cure proved impossible and Joseph died on 22 December 1812 aged forty-four. [13] The family were bereft, feeling as though the prop that held them up had gone. He was remembered fondly by others as a man of "fine mental culture". [9] Mary Anne was thirty-six years old and widowed with seven children, the youngest of whom, Charles, was only a year old. Thankfully Mary Anne and the children were left financially well provided for in Joseph's will but his untimely death must have been exceptionally difficult for the young family to come to terms with. Jane had left school a week before her father's death in order to help her mother care for him. She was fifteen years old and did not return to formal education. Following Joseph's death Mary Anne asked her sister-in-law Sally to move in permanently with her and the children, a request that Sally gladly accepted.

Three months later Mary Anne, Sally, Jane, Robert, Hugh and Charles left London for Peckham where they lived for two years. Frederick, his brother Thomas and sister Mary all joined the rest of the family in Peckham during the summer holidays. There was a desperately anxious time for all when Mary Anne became seriously unwell. She and daughter Mary travelled to Melksham to drink the waters there, and fortunately she recovered. Gradually the household began to be filled with happiness again, although sadly this period of contentment and stability was to be all too short. In the autumn of 1814 Mary Anne, Sally, Jane and the youngest children retired to Hastings on England's south-east coast for a period of three months rest and relaxation. They were joined for a while by Mary Anne's father Thomas Mullett and her sister Sarah. However Thomas was unwell and unfortunately became so ill that he was forced to return to Clapham where very sadly he died on 14 November. Two months later in January 1815 news reached England of the death of Mary Anne's brother-in-law James Webbe Tobin the previous October in the West Indies. The following month Mary Anne's brother Frederick was declared bankrupt and the family business sadly came to an end. [14]

Charles Henry Hall painted by his sister Ann Hall. Attribution: Frick Art Reference Library Photoarchive CC BY 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0), from Wikimedia Commons

This must have been an extremely testing time for all. However there was some happiness to be found as on 30 March 1815 at Holy Trinity Church, Clapham, London, Mary Anne's sister Sarah married Charles Henry Hall (1781-1852). Mary Anne, brother Frederick and daughter Jane, were witnesses, and Jane and her sister Mary were bridesmaids. [15] Charles was an American citizen from Connecticut and brother of renowned American painter and miniaturist Ann Hall (1792-1863). Charles and Sarah subsequently left London for Cadiz, Spain before ultimately settling in America. It must have been a bitter-sweet parting for the sisters when Sarah and Charles left for Cadiz, as they were never to see each other again. Both Charles and Sarah died in Harlem, New York in 1852. Three years after his bankruptcy Frederick also decided to leave London for a new life in America, arriving in Baltimore on 19th June 1818, bound ultimately for St Louis, Missouri. [16]

Melksham, Wiltshire

In 1815 Mary Anne and Sally came to the decision to move the family more than one hundred miles from their Peckham home to the village of Shaw [17] in Wiltshire just outside the town of Melksham. Situated on the River Avon about thirteen and a half miles to the east of Bath, Melksham, which was served by a daily coach service to London and Bath, was, as previously mentioned, the home of Mary Anne's uncle Hugh Foskett Evans (1755-1815). Hugh had very recently died and it would seem that his son Manning Evans (1791-1840) took over the leadership of the boarding school. In 1821 Manning was running the school from a magnificent country house known as Sandridge Lodge near Melksham. The house, which is now Grade II listed, is set in over eight acres of land on a south-facing hillside with views towards Salisbury Plain. An advert for the academy read: SANDRIDGE LODGE ACADEMY Nr Melksham, Wilts. MR EVANS respectfully informs his friends and the public, that the business of the ACADEMY was resumed on the 25th July. The advantages of this beautiful and healthy situation are not surpassed, if equalled, by those of any other in the county. The system of Education in this Establishment is calculated to prepare the pupils either for professional or commercial pursuits. The domestic arrangements are most liberal, and unremitting attention is paid to the health, personal comfort and happiness of the pupils. [18]

In the early nineteenth century Melksham was becoming quite a fashionable place to live and visit, with people being drawn to the purported healing properties of the local mineral waters. Towards the end of the eighteenth century there had been a resurgence in Britain in the habit of 'taking the waters' as a cure for all manner of assorted illnesses, and around the year 1813 Melksham established itself as a spa. In 1815 the Melksham Spa Company was formed and elegant hot and cold baths and a pump room were opened in the summer of 1816 following the successful boring of a three hundred and forty feet deep well just under a mile from the town centre. [19] The local waters were apparently so effective a cure that a Captain Edgecumbe R.N. was able to leave Melksham without his crutches following his treatment at the spa! The crutches were mounted on the wall in the pump room alongside a card attesting to his remarkable cure. [20]

Mary Anne, Sally, Jane and the youngest children spent one year living at Shaw House on Bath Road, Melksham, before moving half a mile along Bath Road to Shurnhold. One prominent family in Melksham at this time were Solicitor and Banker George Moule (1768-1830) and his wife Sarah (nee Hayward) Moule (1764-1835). George and Sarah had married in London in 1785 and had made the move to Melksham during the mid 1790s. They had a large family of twelve children comprising seven sons and five daughters, and the Moule and Evans families soon developed a close friendship. When he was almost seventeen years old Mary Anne's eldest son Thomas decided to train as a Solicitor. On 1 April 1816 he was articled as a Clerk to London Attorney William Stevens of Messrs Swaine, Stevens, Maples and Pearce in Frederick's Place, Old Jewry, London for the term of five years and George and Sarah Moule's son Charles Thomas swore to the affidavit of due execution of the articles of clerkship. [17] Five years later in November 1821, Thomas was joined at the London business by future British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli (1804-1881), and the two young men were to establish a firm friendship. In 1823, at the age of sixteen Mary Anne's son Robert became employed by George Moule in his office in Melksham when he became articled to him as a Solicitor's Clerk. [21]

The following summer ties between the two families were cemented with the marriage on 1 July 1824 at the parish church of St Michael and All Angels, Melksham between Mary Anne's youngest daughter Mary and George and Sarah Moule's sixth son Henry (1801-1880). [22] In August of that same year Benjamin Disraeli was in Heidelberg, south-west Germany on a tour with his father. Whilst there he called on Mary Anne's sister Jane Tobin who had moved to Heidelberg with her children, and gave her a letter informing her of her niece's marriage to Henry Moule. In a letter home to his wife Sarah dated Monday 23 August 1824, Disraeli described Jane as "a cleverish, pleasant woman". [23]Henry Moule was quite a remarkable individual, who, driven to action by devastating cholera epidemics in 1849 and 1854, invented a dry earth closet system for dealing with human waste. In May 1860 his dry earth system was patented and his dry earth closets were adopted widely, both at home and abroad. He had obtained a BA from St John's college, Cambridge and was ordained Curate at Melksham a few weeks after his marriage to Mary. The couple soon moved to Gillingham in Dorset where Henry was appointed Curate in sole charge of the church of St Mary the Virgin in June 1825, before being appointed Vicar of St George's church, Fordington, Dorset in 1829, a post he was to retain until his death on 3 February 1880. Mary gave birth to eight sons, although only seven survived to adulthood; their seventh son Christopher died at the age of fifteen months from atrophy. [24]. Mary, described as having "perfect handwriting and perfect English" [25] appears to have been a deeply loved wife and mother, who dedicated her life to supporting her husband's ministry. She was superintendent of the girls' Sunday School and made daily visits to each household in the village regardless of weather conditions, checking that all was well, spending time with the sick and helping those in need. Henry and Mary's children grew to lead quite remarkable lives themselves; Henry Joseph became a notable artist, a friend of author and poet Thomas Hardy (1840-1928) and curator of the Dorset County Museum; George became Anglican Bishop of mid-China; Frederick became an Anglican Priest; Horatio (Horace) became a Tutor, an Inspector of Workhouses, and was also a particularly close friend of Thomas Hardy; Charles became President of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge; Arthur became a missionary in China; and Handley was appointed Bishop of Durham from 1901-1920.

By 1826 Thomas Mullett Evans, newly wed to Mary Biggs (b. 1798) the elder daughter of his father's cousin Sarah Evans Biggs, had moved to Bristol, Gloucestershire where he was working as a Solicitor in partnership with Henry Ball from premises on Clare Street. Towards the end of 1824 Thomas and Benjamin Disraeli had become embroiled in a series of disastrous stock market investments whilst in London, which had left them both heavily in debt. In April 1825 the London stock market crashed. By the end of June 1825 Evans and Disraeli had lost almost £7000, half of which it seems had been settled by Thomas in cash. [26] Despite these early financial difficulties however, Thomas appears to have settled comfortably into married life as a Solicitor in Bristol. The following year Mary Anne, Sally and Jane reluctantly decided it was time to leave Melksham and move to Bristol to live with Thomas and Mary. They were extremely sorry to leave Melksham having felt really settled in the local community, but from a financial perspective it made sense to make the move. Family finances had been stretched with the children's education and apprenticeships. By living together they were able to live in a comfortable home in an excellent position in the city, which benefited everyone. Mary Anne's son Robert's articles of clerkship were transferred from George Moule to Thomas in August 1827; [27] son Hugh found work with a Bristol bookseller, William Strong, who had premises on Clare Street; son Charles lived for a while at home in Bristol, before moving north to the city of Birmingham, where he became a lamp manufacturer; and son Frederick Mullett Evans, who had completed an apprenticeship in Bath, lived with the family in Bristol before moving back to London.

Young Adulthood

Sometime around the year 1828, Frederick found work with the publishing house of Thomas Hurst, Edward Chance and Co. They operated from premises at 65 St Paul's Churchyard, just over half a mile away from Frederick's birthplace. This area of London had been at the heart of the country's book trade since at least the early sixteenth century. Whilst he was there good-natured and sociable Frederick formed a close friendship with the poet and soon-to-be publisher Edward Moxon (1801-1858) who was working for Hurst, Chance and Co as a Literary Adviser. [28] Moxon went on to establish his own publishing house on New Bond Street, London in 1830. Evans' and Moxon's deep friendship was to last for thirty years until Moxon's untimely death in 1858.

In July 1829 twenty-five year old Frederick Mullett Evans then made what appears to have been his first foray into the world of business. Showing his entrepreneurial spirit he entered into a partnership with a young man by the name of Francis Joyce (b.1808) [29] in Southampton, eighty miles from London on the south coast of England, running a circulating library under the name of Joyce and Evans. The two young men had taken over the existing business of Charles Gore on Southampton's High Street. Mr Gore was retiring from business due to ill health. However their relationship appears to have been extremely short-lived with their partnership being dissolved just two months after they took over Gore's business. [30] Francis Joyce was one of ten children born to tallow chandler Joshua Joyce (1756-1816) and his wife Mary nee Fagg (1766-1837) of Essex Street, Strand, London. Francis had a brother named Felix (1800-1865) who later became the Chief Accountant/Manager at the firm of Bradbury and Evans. We do not know why the partnership between Francis Joyce and Frederick Mullett Evans ended after just a few months. We do know however that Francis Joyce entered into a disastrous marriage with a woman named Ellen Cox (1810-1876) a month after the dissolution of his partnership with Frederick. This relationship ultimately culminated in Francis committing adultery with one of Ellen's closest friends before absconding with this lover to France where they lived together as husband and wife. [31]

View of part of Stamford Street, Lambeth, London looking West, taken in August 2015. Frederick Mullett Evans and his wife Maria lived on this street for a time in the 1830s. Author's own photograph.

Frederick seems to have returned to London after his brief venture in Southampton and made the acquaintance of William Bradbury. William, a printer and business man to his core, had been in partnership with his brother-in-law William Dent since 1822. The two men had moved from the city of Lincoln, Lincolnshire to London in 1824, where amongst the many publishers they worked for, they carried out printing work for Hurst, Chance and Co at the same time as Frederick was employed by them. I think that this is most probably how William Bradbury and Frederick Mullett Evans met. On 31 December 1829 the partnership between William Bradbury and William Dent was dissolved by mutual consent, and a few months later Bradbury and Evans set up their first printing office together at 1 Bouverie Street, Whitefriars, London. 1830 became an extremely significant year for Frederick with the commencement of his partnership with William Bradbury, and on 21 October his marriage at St Michael and All Angels Church, Melksham to George and Sarah Moule's youngest daughter Maria (1807-1850) [32]. Sadly George Moule had died in February following a very brief illness. The marriage ceremony was very much a family affair; the young couple were married by Maria's brother Horatio Moule (1806-1886), and the marriage was witnessed by Maria's sisters Marianne and Matilda, brother Frederick, and Frederick Mullett Evans' mother Mary Anne.

Maria and Frederick settled into married life in London, making their first home on Stamford Street, Lambeth approximately one mile from Frederick's office in Bouverie Street. No doubt to their great joy Maria quickly became pregnant and their first child, a daughter whom they named Sarah Moule Evans, was born on Wednesday 27 July 1831. [33] Two months later on 29 September 1831 the family gathered at the church of St John the Evangelist, Lambeth as Sarah was baptised by her uncle Horatio Moule, who acted as the officiating minister. [34] Despite the country experiencing a deep financial depression which saw over six-hundred printers out of business by the autumn of 1831, Bradbury and Evans' fledgling business thankfully survived the crisis and thrived due primarily to their keen business sense.

In Bristol Mary Anne, Sally and Jane had moved to a house in Upper Berkeley Place in the Clifton area of the city. Unfortunately Frederick's aunt Sally began to suffer epileptic seizures and his sister Jane's generally weak health took a turn for the worse, leaving her temporarily unable to walk. That autumn, over the course of three days in the October of 1831, rioting broke out in Bristol. Jane recorded that the family were "much afraid" but thankfully suffered no injuries. The previous month the House of Commons had passed Prime Minister Charles Grey's Parliamentary Reform Bill, however this decision was subsequently overturned in the House of Lords. Angered by the House of Lords' rejection of the Reform Bill and the arrival in Bristol on Saturday 29 October of Recorder Sir Charles Wetherell (1770-1846) who was vehemently opposed to the Bill, a hostile crowd took to the streets. The local magistrates had tried to keep Charles Wetherell's arrival time a secret, but somehow word got out and his carriage was spotted attended by officers on horseback armed with swords, and special constables armed with bludgeons. The crowds swelled and his route to the Guildhall in Broad Street was accompanied by shouts from protestors and the throwing of stones and other objects. After conducting his business at the Guildhall Sir Charles made his way to the Mansion House in Queens Square. It was there that the violence escalated between the special constables and the protestors. One man had his skull fractured by a constable and subsequently died. The protestors armed themselves with sticks but were almost immediately disarmed by the constables. The violence however soon resumed. Sir Charles managed to disguise himself and escape over the roof of the building just as the Mansion House came under severe attack. Iron palisades were ripped out and used as improvised weapons; walls were torn down and bricks thrown through windows, and straw was used to set fires. Two cavalry troops were sent for and brought in under the command of Colonel Thomas Brereton (1782-1832). He wished to avoid a massacre and initially refused to attack, imploring the crowds to disperse and to go home. Around midnight however the cavalry charged, slashing at the panic-stricken people with their sabres, severely wounding several. Later on the Sunday morning the crowd regrouped and attacked the Mansion House for a second time, throwing furniture from the windows, smashing china and raiding the wine cellars. The calvary attacked again, but were met by enraged drunken gangs who angrily set about them with their makeshift weapons. Shots were fired and many lives were lost. An incensed crowd surged towards the Bridewell where prisoners were released and the building set alight. A newly erected gaol was attacked, prisoners released and the gaol and the governor's house set ablaze, as were the Bishop's Palace and forty-seven houses in Queens Square. By the Monday morning the city was in the most dreadful state, with buildings reduced to rubble. Shops and businesses remained closed and the cavalry were once again sent in to clear the streets of rioters. Men, women and children ran screaming as they were caught by the military with their sabres; apparently one man was decapitated. Eventually some sort of order was restored to the city, but not before hundreds of people had been killed or severely injured. [35] There is little wonder that Frederick's mother, aunt and sister had been extremely afraid, it must have been absolutely terrifying. Ultimately five of the rioters were brought to trial and hanged despite a petition containing many thousands of signatures being presented to King William IV. A further tragic postscript to the events lies with the fate of Colonel Brereton. He was court-martialled on eleven charges of "conduct wholly incompatible with the duties which devolved on him as an officer having chief command of the troops then in Bristol." [36] The first charge was that although the magistrates had directed him to use force to disperse the rioters, he was accused of "not acting with any vigour or effect, but of having declined, or conducted himself in a feeble manner, calculated only to encourage the rioters." [37] Subsequent charges accused him of repeating the same negligence on further occasions. Colonel Brereton retained Frederick's brother Thomas Mullett Evans as his solicitor for the court-martial. Tragically however, fearing that he would be found guilty as charged, Colonel Brereton shot himself in the heart, dying instantly, on 13 January 1832 after the fourth day of the trial. Jane Mullett Evans recorded that her brother Thomas had "much painful occupation in consequence" of the suicide.

In London when Frederick and Maria's baby daughter Sarah was a just a few months old Maria became pregnant with their second child. However the couple's joy at Maria's new pregnancy was soon overshadowed by the heartbreaking death of baby Sarah on 5 May 1832 at the age of just nine months. Her funeral took place four days later at the church where she had been baptised a mere seven months earlier. Maria and Frederick must have been distraught. In the autumn Maria and Frederick welcomed the safe arrival of their first son, Frederick (Fred) Moule Evans. Although born in London baby Fred was baptised in Maria's home town of Melksham on 13 November 1832.

The business was going from strength to strength, so much so that in 1833 Bradbury and Evans decided to extend, taking over some vacant premises on Lombard Street (now Lombard Lane) around the corner from Bouverie Street. These new premises had been occupied for over thirty years by the highly regarded printer Thomas Davison who had died at the end of 1830. Bradbury and Evans were enthusiastic adopters of new technology and they installed into the Lombard Street premises an enormous, state of the art, steam driven cylinder-press, followed shortly thereafter by the addition of a stereotype foundry. These measures allowed their production speeds to rise rapidly, enabling them to successfully take on much greater workloads.

In Bristol Jane was still struggling health-wise and she and her mother decided to spend some time in Bath, hoping that the spa waters would effect some sort of a cure. They had to return to Bristol after just a few weeks though as aunt Sally became extremely unwell with epilepsy. In the spring of 1834 they returned to Bath, hoping this time to stay for around three months. After less than three weeks however they were summoned home by the most dreadful news; Jane and Frederick's brother Thomas Mullett Evans had died suddenly and unexpectedly at his home in the Kingsdown area of Bristol after just a few hours of illness. He was only thirty-four years old. [38] His death must have come as such a tremendous shock to the family. His poor wife Mary also had to contend with her mother's death just over two months later. Maria and Frederick were expecting another child and when their second son was born later that year he was given the name Thomas Mullett Evans in memory of his late uncle. [39] Apparently Thomas senior's affairs were in a dreadful state at the time of his death and he died insolvent; much-needed financial help for the family came from Mary Anne's sister Sarah in America. At the same time awful news reached the family of the horrific murder of Mary Anne's nephew Henry Mullett onboard the merchant ship Ann sailing from Macau, China. Henry had been the Chief Officer at the time of an attempted mutiny and had been stabbed in the heart, dying almost immediately. Six people were murdered during the attempt and eight crew were severely wounded. [40] Mary Anne, rocked by the death of her son Thomas, retreated with Jane and Sally to Bath. Thomas' widow Mary joined them in Bath for six months, before moving to Stoke Newington, London to live with Frederick and Maria and the children. Frederick employed her as a Reader at Bradbury and Evans for five years, before she sailed for Lima, Peru in the summer of 1840 to live permanently with her brother Matthew Biggs and his family.

The Middle Years

On 20 February 1836 Maria gave birth to their third son, George Moule Evans. Bradbury and Evans had established a reputation for speed, reliability and excellence over the six years they had been in partnership, and by 1836 they were undertaking work for the publishers Chapman and Hall. Ten days before the birth of Frederick and Maria's third son, the publisher William Hall had visited a young writer to ask if he would be willing to compose some text to accompany some comic illustrations created by caricaturist Robert Seymour (1798-1836). This young writer, who agreed to William Hall's proposal, was Charles Dickens (1812-1870). Bradbury and Evans were chosen by Chapman and Hall as the printers for this new work, and on 31 March 1836 the first part of The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club was published in its distinctive green wrappers. Thus began a working relationship between William Bradbury, Frederick Mullett Evans and Charles Dickens that would see Bradbury and Evans as Dickens' publishers from 1844, an association that would last until an acrimonious split with Dickens in 1858.

Maria and Frederick were now living approximately four miles from Bradbury and Evans' premises, at 7 Church Row, Stoke Newington, a house previously occupied by Benjamin Disraeli's grandfather Benjamin Disraeli (1730-1816). This smart terrace of nine two-storey houses was built between 1695 and 1700 on the site of a tudor manor house. As the business thrived so too did family life, with Maria giving birth to a daughter Margaret Moule Evans on 12 June 1837. That winter Mary Anne, Sally and Jane moved back to Bristol from Bath. In Fordington Frederick's sister Mary was struggling to cope as illness raged through her household. Mary Anne immediately travelled the sixty-one miles from Bristol to Fordington, where she moved in to the vicarage to help the family through their crisis. Jane stayed in lodgings in Bristol with aunt Sally, who was again very ill with epilepsy. In the spring of 1838 Mary Anne, Sally and Jane moved once again to Upper Berkeley Place, Bristol. Jane, who had recovered her health, began to teach from their home. She had a daily pupil, held an evening class once a week and also held a singing class.

In May 1839 Frederick and Maria had another son, whom they named Joseph Jeffries Evans after Frederick's father. By the autumn of that same year thirty-two year old Maria was pregnant for the seventh time. However the family's happiness was sadly brought to an abrupt halt in the new year with the death in January 1840 of their youngest son Joseph Jeffries Evans at the tender age of just eight months. Maria was four months pregnant with what would turn out to be their third daughter. On Thursday 23rd January 1840 baby Joseph was buried at the ancient Elizabethan church of St Mary, Stoke Newington. His siblings must have missed their baby brother dreadfully. On Monday 15 June 1840 the family welcomed in a new little life as Maria gave birth to a daughter whom they named Elizabeth Matilda Moule Evans. She became known in the family as Bessie. Another son Horace Moule Evans followed on 8th December the following year.

At this same time Bradbury and Evans' business was prospering. Their premises occupied a large proportion of cramped Lombard Street, where the machine room had six presses thundering along continuously for twelve hours each day. By the end of 1841 Bradbury and Evans had become the sole printers of the weekly satirical magazine Punch, and by the end of the following year had been persuaded by the first editor Mark Lemon (1809-1870) to become the proprietors. At home Maria had help with the house and children in the form of three female servants, one of whom, Frances Ann Whitchurch (1817-1883), was the governess. I should imagine that any and all help was gratefully received by Maria, as she gave birth to her ninth child, a daughter named Mary Josephine Jedidiah Evans, on 20 March 1843, followed by another daughter almost two years later on 12 February 1845. They named this little girl Frances Joan Moule Evans. Tragically just four months after Frances' birth, little Mary Josephine died from inflammation of the bowels aged just two years old. She was the third of their children to die young, and she was buried alongside baby Joseph Jeffries at the church of St Mary, Stoke Newington on 28 June 1845. The previous month in Bristol aunt Sally's health had taken a huge turn for worse and sadly she had become paralysed. She was nursed by Mary Anne and Jane until her death four months later on 30 September at the age of eighty. [41] After a few smaller bequests she left the bulk of her estate to her "sister-in-law and dear friend Mary Anne". She willed that following Mary Anne's death her estate was to pass to her "much loved niece Jane". [42]

By the autumn of 1845 Maria had become pregnant for the eleventh time. The mounting success that Bradbury and Evans were experiencing in their business life contrasts sharply with this period in Frederick's personal life. In February 1846 Frederick's sister-in-law Matilda Katherine Evans, wife of his brother Robert, died from tuberculosis at the age of forty, leaving her husband with five young children, the eldest of whom was only fourteen. Robert was struggling financially, and the wider family immediately rallied round to help. In Bristol Jane and Mary Anne moved to a larger house and as soon as they were settled in they sent for the three oldest children Matilda (Mattie), Godfrey and Katherine (Katie). Three months later Frederick and Maria, no doubt still mourning the loss of their daughter Mary Josephine, were again dealt the cruellest of blows. On 15 May 1846 their youngest daughter Frances Joan died at her home from bronchitis. She was fifteen months old and Maria was eight months pregnant. To add to their trauma, just three days after her death another unexpected blow struck the young family. The Evans' governess Frances Ann Whitchurch, daughter of William Whitchurch, a Bacon Dryer from Goswell Street, Clerkenwell, had a sister named Sarah (1809-1890). Sarah married a Surgeon by the name of David Dodd (1802-1846) and they set up home together at 9 Wildnerness Row, Goswell Street, Clerkenwell. On Monday 18 May 1846 Sarah and David were visiting with Frances at the Evans' home when David became quite unwell. He had been suffering from tuberculosis and very sadly became so unwell during the visit that he died at the Evans' house. [43] Little Frances Joan was buried alongside her brother and sister at the church of St Mary, Stoke Newington, on 22 May 1846. Nineteen days later on 10 June 1846 Maria gave birth to a son, Lewis Moule Evans. This bleakest of times culminated the following month with the tragic death of Frederick's recently widowed brother Robert at the age of forty on 22 July 1846. He sadly died by suicide, having ingested essential oil of bitter almonds. His death left the five children orphans. The Evans family must have been reeling. Mattie and Katie stayed with Mary Anne and Jane in Bristol; Godfrey went to Melksham; the youngest Matthew Flyn Evans, who was just four years old, went to live with his aunt Mary and her husband Henry Moule at the vicarage at Fordington and seven year old Henry Frederick was sent to school in Stoke Newington. Robert's death and the consequences for the children affected sixty-nine year old Mary Anne severely. In the summer of 1847 Maria and Frederick's twelfth and final child, a daughter named Gertrude Moule Evans was born on 16 August 1847. Four of their children went to Bristol to visit with Mary Anne, Jane and their cousins whilst Maria rested. When Horace and Lewis returned home Margaret and Bessie remained in Bristol, joining their cousins Mattie and Katie in their school lessons. Unfortunately all was not well with Frederick's wife Maria.

In the summer of 1848 Jane accompanied Margaret and Bessie to London to visit with Frederick and Maria. It was Jane's first visit to London in twenty years and she was astonished at the changes in the city; the increased noise and bustle, the introduction of omnibuses, and Trafalgar Square which had opened four years previously, all left a particularly vivid impression on her. It was also sadly to be the last time that she saw Maria, who was confined to her couch through illness. Maria had spent the majority of her married life pregnant. Between the years 1830 and 1847 inclusive she had been pregnant and/or giving birth in every year bar one, and this does not take into account any miscarriages that she may have suffered. This must have taken an enormous toll on her body. After Jane's visit Margaret and Bessie returned with her to Bristol, where they stayed until April 1849. At Easter 1849 Mary Anne took the two girls back to London to be with Maria whose health was deteriorating. Maria knew that she was dying and she wanted the children at home with her.

Later Years

On the evening of Thursday 14 February 1850 Frederick wrote a note to Charles Dickens ostensibly about their joint new publication Household Words. However the note contained some distressing news regarding Maria, whose health was by this time declining rapidly. Dickens replied from his Devonshire Terrace home the following day expressing his and his wife Catherine's concern over the news of Maria. [44] She was suffering from a hydrothorax, a congestion of the lungs possibly caused by congestive heart failure. Eight days later, on 23 February, Maria died at the age of forty-two. [45] She left eight surviving children ranging in age from eighteen down to two years old. Maria was buried alongside her children Joseph, Mary and Frances at the ancient church of St Mary, Stoke Newington on 1 March 1850. Writing to William Bradbury a fortnight later, Dickens sent his love to Evans. [46] Widowed at the age of forty-six after a close and loving nineteen year marriage, Frederick never married again. As soon as she received the news of Maria's death Mary Anne left Bristol and went to London to be with Frederick and the children. Whilst Mary Anne helped out with the children in the short-term the longer-term care of the children needed to be addressed. For a while Margaret and Bessie went to a young ladies boarding school on the outskirts of Ramsgate, on England's south-east coast, run by Mary Wilks. The 1851 census for England taken a year after Maria's death shows governess Frances Whitchurch and the two youngest children, Lewis and Gertrude, staying at a lodging house in Brighton, Sussex, [47] whilst Frederick and his son Thomas were staying in a hotel on Harbour Street in Ramsgate, presumably so that they could spend some time visiting with Margaret and Bessie. [48] The oldest son Fred and son George were visiting with Mark Lemon, editor of Punch magazine and his wife Nelly at their home. [49] Son Horace was visiting with his paternal aunt Mary and uncle Henry Moule at the vicarage at Fordington. [50]

On 7 May 1852 Frederick's brother Charles died. [51] He had been admitted to a psychiatric hospital in Bristol the previous July, having spent most of his working life as a Metal Agent and Dealer in Birmingham in the West Midlands. According to their sister Jane, Charles had led a very troubled life, but was deeply loved by all the family, and was greatly missed. Mary Anne had lost three of her adult children, and she felt their deaths profoundly. That same year Frances Whitchurch became seriously unwell and was unable to continue looking after the youngest children Lewis and Gertrude. They initially went to stay with Mary Anne and Jane in Bristol, whilst plans were made for their future. Frederick was keen for his mother, sister Jane and nieces Mattie and Katie to come to live permanently with him in London. In June Mary Anne and Mattie went to London taking Lewis and Gertrude with them, to organise the move and to prepare the London house. However Mary Anne was suddenly taken ill. She had a fit followed by a seizure, and temporarily lost the use of one side of her body. All plans for a permanent move to London were abandoned; Mary Anne returned to Bristol whilst Mattie stayed on in London and took on the role of housekeeper for Frederick.

The following February Frederick arranged for Mary Norton Evans (1805-1863), Sarah Evans Biggs' unmarried niece, to take on the post of governess to Margaret, Bessie, Gertrude and Lewis. Mattie remained with the family as housekeeper, joining in with the children's lessons when she was able. In the autumn of 1853 a celebration was planned for the twenty-first birthday of eldest son Frederick junior. Charles Dickens was amongst the family friends to receive an invitation, but unfortunately he was unable to attend as he would be abroad. In the letter that he wrote to Frederick senior regretting that he would have to decline the invitation, he wrote "And none of your attached friends can hope more ardently than I do, that in the honorable conduct of your children in life, and in their love and affection at home, you may find at once your highest compensation for the loss of their excellent mother, and your gentlest and dearest remembrance of her. [52] Frederick's warm and easy-going nature had enabled the Evans and Dickens families to form quite a close relationship.

In the spring of 1854 Mary Norton Smith took Margaret, Bessie, Gertrude and Lewis to live for a while in Tours in the west of France. Mattie returned to Mary Anne and Jane in Bristol, whilst her sister Kate was sent to school in Epsom, Surrey. Frederick was still very keen for his mother and sister to leave Bristol and to live with him in London, especially in light of Mary Anne's increasing frailty. Mary Anne and Jane agreed, and so Frederick moved to a house on Queen's Road West, Regents Park, London and set up home there, providing a separate sitting room with "every comfort" for Mary Anne. Mattie left Bristol and moved in as housekeeper. On 28 August 1855 Mary Anne and Jane left Bristol for the last time and travelled across the country to take up residence in their new home in London. Jane found leaving their many friends and the wider community in Bristol particularly hard, but eventually became settled in London. Fortunately Mary Anne was extremely happy and comfortable in her new surroundings. However further family difficulties were on the horizon. Frederick's brother Hugh was in business at 29 Clare Street, Bristol as a printer and bookseller, trading with a gentleman named Isaac Arrowsmith (1802-1871) as Messrs Evans and Arrowsmith. It would seem, however, that all was not well with the business. Unbeknownst to Isaac Hugh had got himself into serious financial difficulties and in order to pay back his personal debts he had resorted to taking money from the business. Understandably, when Isaac became aware of Hugh's actions a dispute arose between them, even though Hugh admitted his guilt, and their partnership came to a heated end in November 1855. [53] Hugh was financially ruined, and Mary Anne and Jane also lost money in the debacle. Mattie's brother Godfrey had been employed by Hugh in the business and so unfortunately lost his position. He left Bristol and moved to London, where he spent a great deal of time with his extended family whilst he looked for work. He was eventually successful in finding a position in Guildford. Just before Christmas Frederick visited with Mary Norton Smith in Tours, France and brought Margaret and Bessie back to live in London; Lewis and Gertrude remained in France with Mary. Seventeen year old Margaret then took on her mother's role as mistress of the household.

The new year ushered in a period of quiet contentment and stability for the family. With young Margaret managing the household, Jane devoted herself to Mary Anne's needs; Mattie managed to obtain a position as governess with a family in Hampshire; and Kate obtained a position as a governess in Ireland. In the autumn of 1856 there was great excitement as Lewis and Gertrude returned from France for an extended visit with their father and the rest of the family. Lewis aged ten and Gertrude aged nine had lived in France for two-and-a-half years; Jane delightfully describes them both as being much grown, very shy and very French! They remained at home in London until just before the Christmas period, when their older brother Fred accompanied them back to Tours before returning home himself to spend Christmas in London. Sadly that Christmas Mary Anne was extremely unwell and very weak, but seemed contented and happy and was able to read to Jane in their sitting room as Jane sewed. The following month, January 1857, brought a happy diversion as Frederick's sons Fred, Tom and George took part in performances of The Frozen Deep, a play written in an unofficial collaboration between Wilkie Collins (1824-1889) and Charles Dickens. Jane attended one of these performances at Dickens' home Tavistock House, which she described as affording her an "evening of great pleasure never to be forgotten". Dickens had gone to enormous trouble with the staging of the play; he had previously converted the schoolroom into a miniature theatre, which he extended out the back of the house for this production. Apparently the scenery was "wonderfully good on its tiny scale". [54]

As the year progressed Frederick arranged outings for his mother, accompanied by his sister Jane, to places such as the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, where Mary Anne took a particular interest in seeing the "American plants". In April Frederick's brother Hugh had a last farewell with the family as he left England to begin a new life in Australia. He sailed from London on 20 April on board an American ship the Kingfisher, arriving in Melbourne, Australia almost three months later on 10 July 1857. [55] His family never saw him again. Distressingly Frederick then became seriously unwell with a problem affecting his liver. His doctors recommended that he took some time away from business to rest and recuperate. He went with Margaret, Bessie and George to the small town of Lynton on Devon's coast, where he gradually began to regain his health. However affairs at home were sadly taking a turn for the worse. On Monday 17 August Frederick was urgently summoned back to London as Mary Anne was dying. He fortunately returned in time to see her and for her to recognise that he was there. She spoke his name and was reassured that everyone was with her. Her daughters Jane and Mary together with Frederick sat with her, making her comfortable until she died on Wednesday 19 August at the age of eighty. [56] Widowed with seven children at the age of thirty-six, Mary Anne had been the indispensable glue that held her immediate and extended family together despite devastating personal losses.

Over many years the Evans and the Dickens families had developed a close friendship, socialising and holidaying together. In 1856 Frederick's sons Fred, George and Tom had toured Scotland with Dickens' eldest son Charley (1837-1896). In contrast to William Bradbury's more reserved tone Frederick's naturally extroverted affable nature meant that he was the main intermediary between Dickens and the firm and and the two men enjoyed each others company. In the late spring of 1858 Dickens separated from his wife Catherine. Gossip was rife in London concerning Dickens having an extra-marital relationship with either his sister-in-law Georgina Hogarth or an actress, Ellen Ternan. In an attempt to quell the gossip Dickens issued a public statement regarding the separation, which was published in the Times newspaper on 7 June and in Household Words on 12 June. However, unbeknownst to either Bradbury or Evans, Dickens had expected that his statement would also be published in the following week's Punch. When he realised that the statement had not been printed in Punch he was furious, taking the non-appearance as a personal insult. He resolved to sever all business and personal ties with them as a result. When Bradbury and Evans were informed of this they were in disbelief; as they later wrote "it did not occur to Bradbury and Evans to exceed their legitimate functions as proprietors and publishers, and to require the insertion of statements on a domestic and painful subject in the inappropriate columns of a comic miscellany." [57] Frederick was particularly distressed by Dickens' actions. Dickens forbade his children from ever again visiting Frederick's house. In a letter to Frederick dated 22 July 1858 Dickens wrote "I have had stern occasion to impress upon my children that their father's name is their best possession and that it would indeed be trifled with and wasted by him, if, either through himself or through them, he held any terms with those who have been false to it, in the only great need and under the only great wrong it has ever known. You know very well, why (with hard distress of mind and bitter disappointment), I have been forced to include you in this class. I have no more to say." [58] Dickens returned to his former publishers Chapman and Hall and production ceased of their joint publication Household Words. Dickens ultimately established a new publication All the Year Round and Bradbury and Evans established a new weekly magazine of their own called Once a Week.

In the midst of the collapse of relations with Dickens, Frederick's very good friend Edward Moxon died on 3 June 1858. [59] Bradbury and Evans, trustees of his will, became managers of Edward Moxon's publishing house. We have a wonderfully vivid description of Frederick from this period; he is fondly recalled as "a stoutish, jovial-looking, rubicund-visaged, white-haired gentleman, who, if he had only been attired in gaiters might there and then have been easily taken for the original of Phiz's delineation of the immortal Mr Pickwick." [60]

On 22 September 1859 at the church of St Nicholas, Remenham, Henley on Thames, the Evans family gathered in celebration to witness the marriage of Frederick's eldest son Fred to Amy Lloyd (1838-1926), [61] the youngest daughter of Richard Lloyd (1810-1898), senior partner in the publishing firm of Messrs Lloyd Bros of 96 Gracechurch Street London. Another celebration occurred in August of the following year when Frederick's oldest surviving daughter Margaret married Robert Orridge (1824-1865), a barrister and second son of Charles Orridge (1786-1858) a chemist from Cambridge. The marriage took place on 21 August 1860 at the parish church of St Mark's Regents Park, London. [62] The marriage ceremony was performed by Margaret's uncle Henry Moule, and one of the official witnesses to the marriage was Frederick's business partner William Bradbury. Margaret and Robert's marriage was however all too brief as Robert very regrettably died a little over five years later on 28 December 1865 at the age of forty-one.

Despite the sadly irreconcilable tensions between Dickens and Bradbury and Evans, Dickens' estranged wife Catherine maintained a close friendship with Frederick and his children, frequently dining with him and the family. [63] Dickens' son Charley, who was very close to his mother, also had a deep affection for the Evans family and in particular for Frederick's daughter Bessie; the two had been very close friends since childhood. In 1861 Charley Dickens and Fred Evans established a papermaking business together, and three months later, on 19 November at St Mark's Regents Park, London, Charley Dickens and Bessie Evans were married [64], much to Charles Dickens senior's displeasure. In March of that year Dickens had written a letter in which he expressed the view that Charley "will probably marry the daughter of Mr. Evans the printer — the very last person on earth whom I could desire so to honor me." [65] Unsurprisingly Dickens did not attend the wedding, which was attended by Catherine, and wrote to his very good friend Thomas Beard on 3 November to express his hope that Beard would not enter Evans' house on the occasion of the wedding.

On 4 March 1862 at the beautiful parish church of St Peter and St Paul, Charing, Kent, Frederick's son Thomas married local girl Ellen Mary Wilks (1836-1915), the daughter of Charles Wilks, Surgeon of Charing. That autumn there was great rejoicing in the family as Bessie gave birth to a daughter Mary Angela Dickens on 31 October 1862, making Frederick a grandfather for the first time. As the 1860s progressed however prolonged periods of illness and melancholy struck both Frederick and business partner William Bradbury. Bradbury had suffered a devastating loss from which he never fully recovered with the death by suicide of his eldest son Henry on 1 September 1860. Bradbury and Evans' friend William Makepeace Thackeray died suddenly and unexpectedly from a stroke on 24 December 1863 aged fifty-two and the following October Punch caricaturist John Leech died aged just forty-seven. Evans and deputy Punch Editor Shirley Brooks (1816-1874) had called on Leech on the day of his death after hearing worrying news regarding his health, but had decided not to disturb him as he was resting in bed. [66] His and Thackeray's deaths came as a huge and profound shock to the Punch proprietors and staff. Thackeray and Leech were both buried at Kensal Green Cemetery, north-west London one grave apart from each other; Evans was one of Leech's pallbearers. By the autumn of 1865, both suffering from ill health, William Bradbury and Frederick Mullett Evans felt that the time had finally come to retire from business. Their partnership was dissolved in November 1865, and the firm was handed over to their sons William Hardwick Bradbury and Frederick Moule Evans, who carried on the business as Bradbury, Evans and Co. That same autumn another family wedding took place with the marriage on 14 September at Melksham, Wiltshire of Frederick's son George with Emily Sarah Moule (1837-1884), daughter of Maria's late brother Charles Thomas Moule (1800-1865). The following April in Jhansi, Bengal India where he was serving with the 104th Regiment Bengal Fusiliers, Frederick's son Horace married Elizabeth Annie Tressider (1847-1929), eldest daughter of John Nicholas Tressider (1819-1889), Surgeon-Major of the Indian Medical Service. [67]

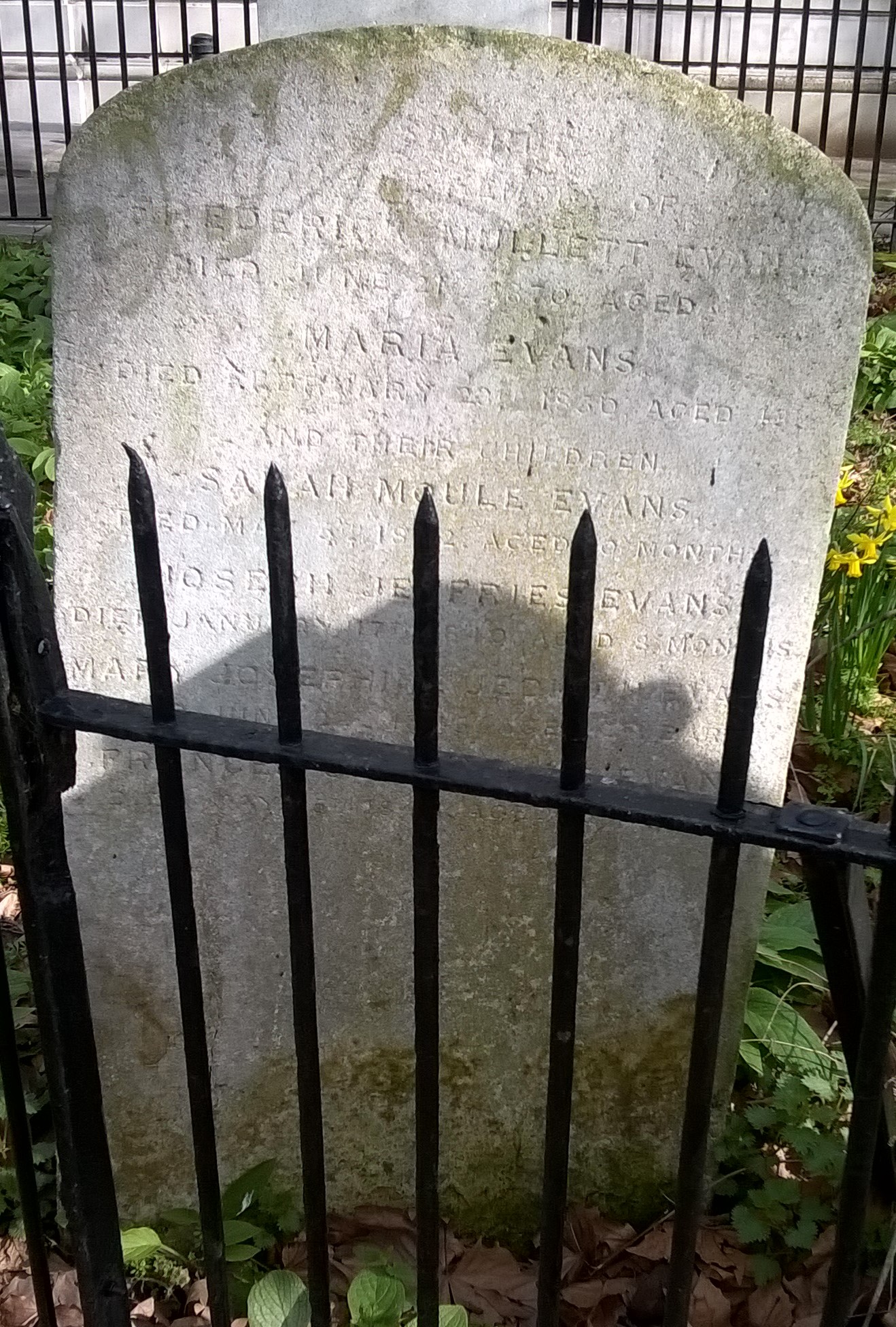

Headstone of Frederick Mullett Evans, his wife Maria and their children at St Mary's Old Church, Stoke Newington, London. Author's own photograph.

Towards the end of his life Frederick invested his savings in the Kennet Papermaking Co, a papermaking business managed by his son Fred, daughter-in-law Amy's father Richard Lloyd and Charley Dickens. This proved to be a financially ruinous decision when the company collapsed in the summer of 1868. A notice placed in the Reading Mercury on 22 August 1868 stated that Public Accountant George Augustus Cape of 8 Old Jewry in the City of London had been appointed to be the Provisional Official Liquidator of the company on 20 August 1868. On Monday 28 September 1868 at one o'clock in the afternoon the 'stores and effects' of the company were auctioned off on the premises at Sheffield Mill, Theale, Reading. [68] That autumn Frederick Mullett Evans was declared bankrupt. The London City Press reported on 14 November 1868 that "The bankrupt, described as a gentleman, came before the court on his own petition, and thus he explained his inabilities to meet his engagements - "The failure of Kennett Paper-Making Company (Limited), of which I was one of the directors, and of which company I and the other directors guaranteed debts. I was led to believe - and did believe - that the company was in a flourishing position, and that my guarantee would only be nominal, and that I should never be called upon to pay it; but to my surprise the company stopped payment in July in the present year, with liabilities to a very large amount and very small assets. But for this I should have been able to meet my engagements." The unsecured debts were about £25,000; and a further sum of £3,500 was secured by the deposit of bonds and policies of assurance." Managing Director Richard Lloyd was also declared bankrupt. The Daily Telegraph and Courier of 15 January 1869 recorded "The bankrupt was described as of Cannon-street, City, managing director of the Paper-making Company (Limited). He had formerly been in partnership under the style of Lloyd Brothers, picture dealers. The liabilities were stated at £23,622 of which £15,834 was a contingent liability, in connection with the above company, which is now in course of liquidation. The assets consist of £6,700, returned as doubtful debts."

On 11 April 1869 Frederick's friend and business partner William Bradbury died at home in Upper Woburn Place, London aged sixty-nine; that autumn Frederick himself fell seriously ill with a kidney complaint from which he was not to recover. On Tuesday 21 June 1870, one month after the death of Punch editor Mark Lemon, Frederick died at his son Fred's home aged sixty-six. The cause of death was given as albuminuria and dropsy. He was buried four days later on 25 June alongside Maria and the children at the parish church of St Mary, Stoke Newington. A wonderfully touching tribute to Frederick appeared in Punch on Saturday 2 July 1870. It stated: "Again, and after sadly brief lapse, we speak of mourning. We deplore the loss of our old, warm-hearted, faithful friend, FREDERICK MULLETT EVANS, who, after severe illness, borne with manly constancy, now rests from the labours of an energetic and honourable life. He was endowed with high abilities, which he exercised with unflagging vigour almost to the end; and his generous nature chiefly prized worldly success because it enabled him to promote the happiness of those who shared his love. His course is finished, his work is done, and they who inscribe these lines to his memory will never lament a more kind, more genial, or more loyal friend."

References

- ^ Guildhall, St Botolph Bishopsgate, Register of marriages, 1793 - 1802, P69/BOT4/A/01/Ms 4520/6

- ^ Moule H.C.G. (1913) Memories of a Vicarage

- ^ London Courier and Evening Gazette 30 Jan 1809

- ^ London Metropolitan Archive; Reference Number: COL/CHD/FR/02/1203-1212

- ^ Kent's Directory 1803

- ^ See London, England, Proceedings of the Old Bailey and Ordinary's Accounts Index, 1674-1913 26 Oct 1796

- ^ Morning Chronicle 4 October 1808

- ^ Morning Chronicle 13 December 1810

- ^^ Moule H.C.G. (1913) Memories of a Vicarage p. 65

- ^ Robinson H.C. Ed. Sadler Thomas 1869 Diary, Reminiscences, and Correspondence of Henry Crabb Robinson, Volume 2 p. 44

- ^ see Dissenting Studies 1660-1850, Timothy Whelan, Georgia Southern University, British Baptist Letters, 1700-1860, Steele Mary Footnote 41

- ^ Wakefield Priscilla, Perambulations in London, and Its Environs p. 440

- ^ London Courier and Evening Gazette 25 December 1812

- ^ Morning Chronicle 15 February 1815

- ^ London Metropolitan Archives, Holy Trinity, Clapham, Register of marriages, P95/TRI1, Item 110

- ^ National Archives; Washington, D.C.; ARC Title: Naturalization Petitions for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania, 1795-1930; NAI Number: 369; Record Group Title: M1522

- ^^ The National Archives of the UK (TNA); Kew, Surrey, England; Court of King's Bench: Plea Side: Affidavits of Due Execution of Articles of Clerkship, Series I; Class: KB 105; Piece: 26

- ^ Salisbury and Winchester Journal 30 July 1821

- ^ Oxford University and City Herald 16 March 1816

- ^ Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette 27 May 1819

- ^ The National Archives of the UK (TNA); Kew, Surrey, England; Court of King's Bench: Plea Side: Affidavits of Due Execution of Articles of Clerkship, Series II; Class: KB 106; Piece: 8

- ^ Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre; Chippenham, Wiltshire, England; Wiltshire Parish Registers; Reference Number: 1368/17 Wiltshire, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1754-1916

- ^ Monypenny, William Favelle (1910) Life of B Disraeli Vol 1 1804-1837 p. 51

- ^ England & Wales, Free BMD Death Index, 1837-1915 Name Christopher Cooper Moule, Registration Year 1839, Registration Quarter Apr-May-Jun, Registration district Dorchester, Inferred County Dorset, Volume 8, Page 37

- ^ Moule H.C.G. (1913) Memories of a Vicarage p.66

- ^ Monypenny, William Favelle (1910) Life of B Disraeli Vol 1 1804-1837 p. 55

- ^ The National Archives of the UK (TNA); Kew, Surrey, England; Court of King's Bench: Plea Side: Affidavits of Due Execution of Articles of Clerkship, Series II; Class: KB 106; Piece: 13

- ^ Merriam Harold G (1939) Edward Moxon Publisher of Poets Columbia University Press p. 11

- ^ The National Archives of the UK; Kew, Surrey, England; General Register Office: Birth Certificates from the Presbyterian, Independent and Baptist Registry and from the Wesleyan Methodist Metropolitan Registry; Class Number: RG 5; Piece Number: 39

- ^ London Evening Standard 26 September 1829

- ^ Western Daily Press 09 June 1865

- ^ Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre; Chippenham, Wiltshire, England; Reference Number: 1368/18 Wiltshire, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1754-1916

- ^ Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette 11 August 1831

- ^ London Metropolitan Archives, Lambeth St John the Evangelist, Register of Baptism, p85/jna3, Item 002

- ^ The Examiner 06 November 1831

- ^ Morning Post 30 December 1831

- ^ The Times (London, England), Saturday 7 January 1832

- ^ Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette 15 May 1834

- ^ Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre; Chippenham, Wiltshire, England; Wiltshire Parish Registers; Reference Number: 1368/9

- ^ Morning Advertiser 29 April 1834

- ^ England & Wales, Free BMD Death Index, 1837-1915 Registration Year 1845; Registration Quarter Oct-Nov-Dec; Registration district Bristol; Inferred County Gloucestershire; Volume 11; Page 85

- ^ The National Archives; Kew, England; Prerogative Court of Canterbury and Related Probate Jurisdictions: Will Registers; Class: PROB 11; Piece: 2026

- ^ London Daily News 20 May 1846

- ^ The Letters of Charles Dickens: 1820-1870. (2nd Release) Electronic Edition. Volume 6: 1850-1852 To F. M. Evans, 15 February 1850

- ^ Devizes and Wiltshire Gazette 28 February 1850

- ^ The Letters of Charles Dickens: 1820-1870. (2nd Release) Electronic Edition. Volume 6: 1850-1852 To William Bradbury 14 March 1850

- ^ 1851 England Census Class: HO107; Piece: 1646; Folio: 237; Page: 64; GSU roll: 193551

- ^ 1851 England Census Class: HO107; Piece: 1630; Folio: 343; Page: 15; GSU roll: 193531

- ^ 1851 England Census Class: HO107; Piece: 1697; Folio: 65; Page: 32; GSU roll: 193605

- ^ 1851 England Census Class: HO107; Piece: 1858; Folio: 160; Page: 7; GSU roll: 221005-221006

- ^ Registration Year 1852; Registration Quarter Jul-Aug-Sep; Registration district Clifton; Parishes for this Registration District Clifton; Inferred County Gloucestershire; Volume 6a; Page 96

- ^ The Letters of Charles Dickens: 1820-1870. (2nd Release) Electronic Edition. Volume 6: 1850-1852 To F.M. Evans 10 September 1853

- ^ Perry's Bankrupt Gazette 01 December 1855

- ^ The Examiner 17 January 1857

- ^ Victoria, Australia, Assisted and Unassisted Passenger Lists, 1839–1923 Series: VPRS 7666; Series Title: Inward Overseas Passenger Lists (British Ports)

- ^ Morning Post 24 August 1857

- ^ Once a Week Mr Charles Dickens and His Late Publishers Volume 1, Number 1 July 2 1859

- ^ Pilgrim Edition Letters of Charles Dickens Volume 8: 1856-1858

- ^ Morning Chronicle 07 June 1858

- ^ Ellis, Stewart Marsh (1920) George Meredith; his life and friends in relation to his work p. 106

- ^ Oxford Journal 01 October 1859

- ^ London Metropolitan Archives, Saint Mark, Regent'S Park, Register of marriages, P90/MRK, Item 005

- ^ Nayder, Lillian (2012) The Other Dickens: A Life of Catherine Hogarth p. 278

- ^ London Metropolitan Archives, Saint Mark, Regent's Park, Register of marriages, P90/MRK, Item 005

- ^ The Letters of Charles Dickens: 1820-1870. (2nd Release) Electronic Edition. Volume 9: 1859-1861 To MRS NASH, 5 March 1861

- ^ Houfe Simon (1984) John Leech and the Victorian Scene p. 206

- ^ Evening Mail 30 May 1866

- ^ Berkshire Chronicle 26 September 1868