Charles Hicks - Foreman Printer

Charles Hicks (c1799-1870) was born in the market town of Ringwood, Hampshire, England around the year 1799. He was one of at least two sons born to Samuel Hicks, a Barrack Master's Sergeant at the Tower of London. His father had died sometime before March 1816 when Charles began an apprenticeship under printer David Samson Maurice (1785-1828) of Fenchurch Street, London. [1] David Maurice was also the principal proprietor of the ill-fated Royal Brunswick Theatre which briefly stood on Well Street (now Ensign Street) in the Tower Hamlets district of London. The newly built theatre opened on Monday 25 February 1828 and tragically collapsed late in the morning of Thursday 28 February 1828 due to the failure of the iron-framed roof. Several people were killed in the disaster, including David Samson Maurice. [2]Hicks is one of the better known of the employees of William Bradbury and Frederick Mullett Evans; he was their Foreman when Bradbury and Evans were printing the works of Charles Dickens for the publishing firm of Chapman and Hall. As such he is mentioned several times in the correspondence of Charles Dickens. I have been able to find very little about the early life of Charles Hicks. He had an older brother Samuel Hicks [3] born around 1787 in London, who worked variously as a soldier and as a hairdresser. We know that Charles married a woman with the first names of Mary Ann who was approximately nine years his junior and who was born in Monken Hadley in the present day London borough of Barnet. Whilst working for Bradbury and Evans Charles and Mary lived at the heart of the business, at number 4 Bouverie Street, Fleet Street, London; [4] Bradbury and Evans ran their business from Bouverie Street and also from the adjacent Lombard Street (now known as Lombard Lane).

Between 31 March 1836 and November 1837 twenty-four year old Charles Dickens had his first novel published under the title, The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club. This was published in nineteen monthly parts (the last being a double length issue) by the publishing house of Chapman and Hall. Dickens' novels were sold in these monthly parts with distinctive green printed covers, at the price of one shilling each; the double length issue was priced at two shillings. As the Foreman at the printing offices of Bradbury and Evans, Hicks was in immediate direct contact with Dickens. Dickens would send his handwritten manuscripts round to Bradbury and Evans to be typeset, or sometimes Hicks would arrange for one of the printers' boys to be sent the short seven minute walk to Dickens' rented rooms at Furnivals Inn to collect a finished proof. Most of these manuscript pages were disposed of, being not needed once the type had been set, however the canny Hicks retrieved and kept in his possession about fifty pages of The Pickwick Papers, perhaps as the issues started to become something of a sensation with the public. In October 2011 the auction house of Bonhams in New York sold one of these handwritten pages from the thirteenth issue, printed in March 1837, for $60,000 or £38,939.

Cover of Charles Dickens' The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club published by Chapman and Hall, printed by Bradbury and Evans. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Dickens, Bradbury and Evans all appear to have held Hicks in high regard and in July 1837 Dickens composed a witty little rhyming poem addressed to Hicks, which started: ...I'm heartily sick of this sixteenth Pickwick. [5] Hicks was a Freeman of the Worshipful Company of Stationers (the Stationers' Company), the author Samuel Richardson had been a former Master, and in 1838 put himself forward for election to the office of Beadle, an important administrative role. Dickens wholeheartedly and enthusiastically supported his application, and wrote to the publisher Richard Bentley (1794-1871), founder of the literary magazine Bentley's Miscellany, urging him also to support Hicks' application saying that he knew him to be "a man of very high character and deserts". [6] Unfortunately, despite this high praise, Hicks was unsuccessful in his petition, coming in third place in the election out of the four applicants.

Hicks also oversaw the printing of Dickens' next Chapman and Hall novel, The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby, which was again published in nineteen monthly issues, with the last part being a double issue. Nicholas Nickleby was published with Dickens' now familiar green wrappers, between March 1838 and September 1839. As he did after completing all the parts of The Pickwick Papers, Dickens threw a celebratory 'end of novel' dinner party on Saturday 5 October 1839 at the Albion Tavern, 153 Aldersgate Street, to which amongst other friends, he invited his publishers Chapman and Hall, Bradbury, Evans and Hicks.

Illingworth and Hicks

According to an announcement placed in the Leeds Mercury newspaper on Saturday 7 August 1841, Charles Hicks appears to have commenced working for William Bradbury sometime around the year 1826, when the printing firm would still have been under the ownership of William Bradbury and his brother-in-law William Dent. This newspaper announcement marked a new and exciting venture for Hicks. It would appear that Hicks had ambitions to run his own printing establishment. To that end, together with a friend and neighbour Henry Illingworth, he had become the proprietor of a printing and bookselling business in the city of Wakefield, West Yorkshire. The two friends had taken over the business of Richard Nichols (d. 21 April 1849), who had been a bookseller, bookbinder, and printer in the market place in Wakefield for thirty-one years. After thanking his many friends and the public for their support over the years, Nichols' retirement notice in the Leeds Mercury went on to say:

"Richard Nichols begs to announce that his Business is now transferred into the very able and respectable hands of HENRY ILLINGWORTH, formerly an Apprentice with the late Messrs Todd of York, and who has since had a lengthened Experience in the well-known Establishment of Messrs Longman, Brown, Green and Co, Paternoster Row; and CHARLES HICKS, from the Firm of Messrs Bradbury and Evans, Printers, Whitefriars, London, whose business he has superintended for upwards of fifteen years."

The Monthly Literary Advertiser later carried an announcement which read:

".....HENRY ILLINGWORTH AND CHARLES HICKS From the houses of Messrs. Longman and Co., and Bradbury and Evans, the London and Country Trade are respectfully solicited for the favour of Agencies; also for Catalogues, Prospectuses, &c., which may be sent either direct or through their Correspondents, Messrs. LONGMAN and Co. Wakefield, Aug. 24th 1841."

There is an undated letter from Charles Dickens to Bradbury and Evans, which the Editors of the Pilgrim Edition of The Letters of Charles Dickens have dated to April 1838, which I believe may reference the fact that Hicks had left Bradbury and Evans. Towards the end of the short letter Dickens wrote:

"Mr Hicks, I presume, is no more. Poor fellow! He fell a victim to a rash spirit of enterprise, and I regret him deeply." [7]

I believe that the phrase "Hicks, I presume, is no more", may indicate that Hicks was no longer employed by Bradbury and Evans. The rash spirit of enterprise that Dickens jokes that Hicks had fallen a victim to, is I speculate, Hicks setting up his own business. The Pilgrim Editors speculate that in this sentence Dickens is possibly joking about Hicks' unsuccessful attempt to be elected as Beadle to the Stationers' Company, however I think it is more likely that he is referring to a new business endeavour.

Hicks' new business partner, Henry Illingworth, was born in the city of York on 8 May 1810, the son of a Maltster named Joshua and his wife Margaret. A month after forming the new partnership of Illingworth and Hicks, Henry Illingworth married Catherine Elizabeth Estill in the church of St Paul in Liverpool, [8] and the young family set up home together in Wakefield alongside Charles Hicks and his wife Mary Ann. For almost ten years Illingworth and Hicks carried on a successful, thriving, bookselling and printing business in the Market Place in Wakefield. They valued individuals' private libraries, undertook bookbinding, printing and publishing and in October 1848 opened a circulating library. Business was going well. However on Wednesday 9 April 1851 Henry Illingworth suddenly became very sick. He was attended by his doctor Mr John Horsfall, who described him as being "very nervous and wild in his manner". The following day he was no better, was unable to sleep and Mr Horsfall advised Catherine not to leave her husband alone. However when Mr Horsfall visited on the Friday morning, Henry Illingworth appeared much calmer and said that he had had such a good night that he felt able to return to work that day. Catherine also felt that he seemed to be much more collected, and was pleased to see that he had washed and shaved himself. After Mr Horsfall left, Illingworth went to the outside privy at the bottom of the garden. A friend, Mr Balmforth, from a nearby firm came to visit to see how he was feeling. Catherine went outside and passed on Mr Balmforth's message to her husband, who told her not to pass on any return message as he would be back inside the house shortly. However several minutes passed and Henry had not returned, so Catherine went back outside to look for him. To her absolute horror she found her husband lying dead on the floor in a pool of blood with a razor at his side; tragically Henry Illingworth had committed suicide. The shock felt by his family, friends and the wider community in Wakefield was considerable. An inquest was held and after the evidence was heard the inquest jury returned as their verdict "that the deceased committed suicide during a fit of temporary insanity". He was buried in Wakefield on 15 April 1851. [9]

A month later Charles Hicks placed a notice in the Leeds Intelligencer newspaper to say that he was carrying on the business that he had run with his deceased partner and that he hoped that "by careful attention to the execution of all orders confided to him, that he will retain the confidence reposed in the late Firm" [10] Hicks did indeed successfully carry on the business. At the time of Illingworth's death they were employing ten men, one of whom was an Assistant/Manager by the name of Benjamin Willoughby Allen. He was to be a great help to Hicks with the day to day running of the business following Illingworth's death. A few years later there was sadly another great tragedy for Charles Hicks with the death of his wife Mary Ann on Saturday 17 November 1855. She was forty-seven years old. Mary Ann was buried at the parish church of St John the Baptist in Wakefield three days after her death. [11] Hicks and William Bradbury had remained close friends, and Charles Dickens also retained a fondness for Hicks. Writing to Bradbury and Evans just after Mary Ann's death in November 1855, Dickens said:

"I am sorry to hear of poor Hicks's misfortune. When you write to him, pray tell him that I sent my regard and sympathy." [12]

Jenny Goldschmidt Lind photographed by John Carl Frederick Polycarpus Von Schneidau in September 1850. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Hicks embraced both his business and social life in Wakefield. A natural organiser, five months after the death of his wife he arranged for the Swedish born opera singer Madame Jenny Goldschmidt Lind (1820-1887) to perform a concert in the Corn Exchange Buildings in Wakefield. A soprano singer, Jenny Lind was hugely admired throughout Europe and America, undertaking sell-out tours and performances particularly during the 1840s. She was a great favourite of Queen Victoria. Lind and her husband the composer and pianist Otto Moritz David Goldschmidt (1829-1907) moved permanently to England in 1858 where she undertook charitable work, giving concerts without charging a fee. On the day of the concert, Saturday 5 April 1856, a palpable excitement filled the town of Wakefield. The parish church bells rang out as carriages brought spectators from all around the district, and local people gathered animatedly awaiting the arrival of the great star. Her performance lasted for around two and half hours and was described as being 'unrivalled'. [13] A month later Charles Hicks received a letter from Otto Goldschmidt thanking him for his attention in the arrangements of the visit, and enclosing a gift for him of some pearl dress shirt studs, which were mounted in gold and blue enamel. [14]

Hicks and Allen

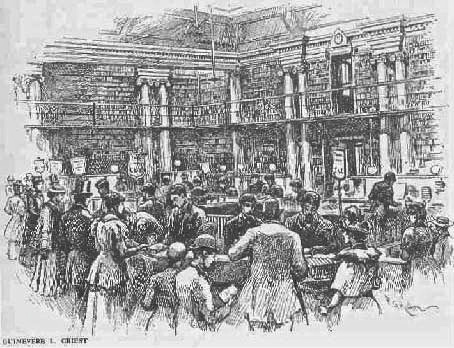

At the start of 1858 Hicks made his friend and manager Benjamin Willoughby Allen a joint partner in the business, which was then to be known as Hicks and Allen. [15] A publisher and stationer by the name of Charles Edward Mudie (1818-1890) had set up a lending library at his shop in London in 1840.

Sketch showing the interior of Mudie's Lending Library, New Oxford Street, London. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Even though he had left their business Hicks retained a very close friendship with William Bradbury and the wider Bradbury family. They holidayed together and shared important family events. In July 1858 William Bradbury and Charles Hicks stayed at the Britannia Hotel on Bridlington Quay in the coastal resort of Bridlington, East Yorkshire. [17] The Britannia Hotel had just undergone an extensive refurbishment, and the up-and-coming seaside resort was at that time planning improvements at the Quay in order to make it more attractive to the increasing numbers of visitors that were starting to flock to the east coast. In 1865 William and Sarah Bradbury, now retired from business, and Charles Hicks holidayed together in the seaside town of Whitby, North Yorkshire, staying on the Royal Crescent. [18] On Thursday 6 December 1860 William Bradbury's second son William Hardwick Bradbury, married Laura Agnew at the church of St Mary in the town of Eccles, Lancashire in what must have been a somewhat bittersweet ceremony. Bradbury's eldest son Henry Riley Bradbury had tragically committed suicide just three months previously by drinking prussic acid. The witnesses to the marriage, who all signed their names on the marriage certificate, were William and Sarah Bradbury, their son Walter, daughter Edith, Frederick Mullett Evans and Charles Hicks. [19]

Hicks and Allen continued together in business until Charles' death in Southsea, Hampshire on Christmas Day 1870. At the time of his death they were employing eight men, two women, ten boys and one girl in the business in Wakefield. Hicks had appointed Bradbury's eldest surviving son William Hardwick Bradbury as one of the executors of his estate. In his will Charles left bequests to each of the surviving children of William and Sarah Bradbury. Touchingly he also made a gift of one-hundred pounds to Miss Amelia Turner, a nurse employed by the Bradbury family for over thirty years. One of the pieces of jewellery that Charles bequeathed William Hardwick Bradbury were the pearl dress studs that had been given to him in 1856 by the singer Jenny Lind. [20]

References

- ^ see London, England, Freedom of the City Admission Papers, 1681-1925 for Charles Hicks 5 March 1816

- ^ Globe 29 February 1828

- ^ London, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1754-1932; London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; Reference Number: p85/mry1/421

- ^ 1841 England Census Class: HO107; Piece: 728; Book: 9; Civil Parish: White Friars Precinct; County: Middlesex; Enumeration District: 13; Folio: 25; Page: 12; Line: 12; GSU roll: 438832

- ^ The Letters of Charles Dickens: 1820-1870. (2nd Release) Electronic Edition. Volume 1: 1820-1839 To CHARLES HICKS, 26 JULY 1837

- ^ The Letters of Charles Dickens: 1820-1870. (2nd Release) Electronic Edition. Volume 1: 1820-1839 To RICHARD BENTLEY, ?19 MARCH 1838

- ^ The Letters of Charles Dickens: 1820-1870. (2nd Release) Electronic Edition. Volume 1: 1820-1839 To MESSRS BRADBURY & EVANS, ?APRIL 1838

- ^ Liverpool Record Office; Reference Number: 283 PAU/3/6

- ^ Manchester Courier and Lancashire General Advertiser 19 April 1851

- ^ Leeds Intelligencer 24 May 1851

- ^ West Yorkshire Archive Service; Wakefield, Yorkshire, England; Yorkshire Parish Records; Old Reference Number: D45/1/29; New Reference Number: WDP45/1/4/4

- ^ The Letters of Charles Dickens: 1820-1870. (2nd Release) Electronic Edition. VII,745.18. To MESSRS BRADBURY & EVANS, ? MID-NOVEMBER 1855

- ^ Leeds Mercury 08 April 1856

- ^ Leeds Times 10 May 1856

- ^ Leeds Intelligencer 9 January 1858

- ^ Leeds Intelligencer 19 November 1859

- ^ Hull Packet 30 July 1858

- ^ Whitby Gazette'' 16 September 1865

- ^ Manchester, England, Marriages and Banns, 1754-1930

- ^ England & Wales, National Probate Calendar (Index of Wills and Administrations), 1858-1966