Joyce and Evans

169 High Street, Southampton, Hampshire, England

"CHARLES GORE having relinquished his Business in consequence of ill health, begs very sincerely to offer his thanks for the extensive patronage shown him since his first establishment here, and to hope the same interest will be continued to his successors, Messrs. JOYCE and EVANS, whom he has much pleasure in introducing to their notice."

In July 1829 readers of the Salisbury and Winchester Journal would have seen this announcement introducing them to the firm of Messrs Joyce and Evans. [1] Charles Gore had owned a circulating library in Southampton on England's south coast for approximately six years. He was handing over his business to the partnership of Francis Joyce (b.1808) [2] and Frederick Mullett Evans (1804-1870), later one of the founding partners of the London printing and publishing firm of Bradbury and Evans. It would seem however that the partnership of Joyce and Evans was an extremely short-lived affair. According to the London Gazette their partnership was dissolved on 1 September 1829, a mere two months after they took over the proprietorship of Gore's circulating library. [3]

Both Joyce and Evans were native Londoners. Frederick Mullett Evans had been born on 29 January 1804 [4] in Staining Lane, London, approximately five minutes walk from St Paul's Cathedral. Francis Joyce, born on 23 March 1808 in Essex Street, Strand, London, was a younger brother of Felix Joyce (1800-1865), who later became the Chief Accountant/Manager at the firm of Bradbury and Evans. Francis was from a large family of ten children, being the youngest child of tallow chandler Joshua Joyce (1756-1817) and his wife Mary nee Fagg (1766-1837). Both the Joyce and Evans families were prominent members of the non-conformist church and I feel it is highly likely that the wider families would have known one another.

Drawing of Southampton High Street in 1839. Public Domain, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3990060

Situated at the heart of the city on the High Street and described as "elegant and well stored" [5] Joyce and Evans' Circulating Library was open to subscriptions for membership from both ladies and gentlemen. In addition to the well-furnished library which contained all the "new and proper works" they gave the people of Southampton the chance to read the daily and evening newspapers and popular periodicals in their Reading Room, as well as offering for sale stationery, drawing materials, engravings which were sent down from London, maps and globes. They also provided book-binding, engraving and printing services which they declared would be executed "in the best style". [6]

Despite their enthusiastic initial announcements the fledgling relationship between Joyce and Evans dissolved almost as soon as it commenced. It would appear that Frederick Mullett Evans returned to London, where at the beginning of the following year he formed the partnership of Bradbury and Evans with printer William Bradbury (1799-1869), a partnership that was to last until their joint retirements in 1865. Francis Joyce remained in Southampton and a month after the dissolution of his business partnership he married Ellen Cox (1810-1876). Ellen was the daughter of William Cox (1771-1835), a Silk Mercer and his wife Sophia (nee Bayly) (b.a.1770-1839), and they married in her home city of Bath, Somerset, some sixty-three miles from Southampton. Francis was twenty-one years old and Ellen just nineteen years old.

It would seem that for the first few years of their marriage all was well with Francis and Ellen. They lived in Southampton and continued to run the Circulating Library on the High Street. On 1 January 1831, alongside the general library, Francis opened the Hants Medical and Surgical Library, with the object of enabling "Practitioners and Students to avail themselves, on moderate terms, of the advantages of the Medical Press, and to form a MEDICAL AND SURGICAL LIBRARY, which, after a short period, will rise into consideration and importance." [7] He continued to develop the business; after seven years of trading the library seemed to be a rather grand affair which included a Club Room, Reading Room and a Saloon of Arts offering "a Collection of everything connected with the Studio and the Ornamental Accessories of the Drawing Room and Boudoir." [8] However early in 1837 newspapers were listing Francis Joyce as bankrupt, [9] and by April of 1837 Joyce's Circulating Library was under the new proprietorship of a Mr John Coupland.

Desertion and Adultery

Newspaper reports from almost thirty years later paint an interesting if rather depressing picture of the subsequent lives of Francis and Ellen. It transpires that during their time in Southampton Francis had been unfaithful to Ellen, committing adultery with one of her closest friends. In February 1837, following his declaration of bankruptcy, he had abandoned Ellen and had gone on the run to start a covert life with his mistress. [10] Together Francis and his lover, a Miss Yearsley, had travelled and stayed in various places around England, before heading across the English Channel to start a new life in the north west region of France. Before he left England Ellen had managed to send word to Francis several times, imploring him to return to her and trying to appeal to his sense of duty, but in vain. Friends of Miss Yearsley had intervened and twice had found her and taken her home, but both times Francis determinedly managed to persuade her to return to him. Once in France they changed locations frequently to avoid detection, living in places such as Granville, Avranches, Caen, Lorient and Nantes, before settling in Quimper, Brittany. There they set up home together as husband and wife, established themselves in the local community and had three children, all without any one being aware of their secret. Francis somehow managed to set up in practice as a medical man which was rather a change from a librarian and bookseller! One of their children, a son known as Monsieur Gregoire, became a dentist as an adult living and working in Lorient. [11]

Meanwhile, in England, abandoned by her husband and betrayed by her friend, Ellen had very little choice but to move away from Southampton back to her family. As a married woman in England at the start of the Victorian era, Ellen had no independent legal rights and would not have been viewed legally as a self-determining individual. It would have been absolutely impossible for her to file for a divorce in 1837 and Francis as her husband would have legally owned all of her money and property.

Ellen would have known that she was returning from Southampton to an equally disrupted and dysfunctional set of family circumstances. Her parents had moved from her birth city of Bath to Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, where her father had died in December 1835 aged sixty-three after a long illness, leaving her widowed mother alone. Ellen had two older sisters, Sophia Ann (1802-1860) and Louisa (1806-1836), and an older brother William Hawkins Cox (1800-1862). Sophia had married William Bissex Moore (1808-1860) in 1824 and they lived in Bath with their young family. Louisa had married family friend Charles John Morris (1807-1874) in 1829. After living in Cheltenham they had moved to Swansea, Wales, where tragically Louisa had died in June 1836 just after giving birth to their third daughter. Her husband, an auctioneer, was left with the children aged just five and two and the newly born baby. Ellen's brother William Hawkins Cox had married Anna Cowley in Cheltenham where they had had eight children. William had become editor of the Cheltenham Chronicle newspaper, but following some sort of financial irregularities towards the end of 1835, he had abandoned his wife and young children and had fled to America. There he had obtained a position as Special Correspondent of the Pennsylvania Inquirer newspaper and had changed his surname to Crump. [12]

Ellen's sister-in-law Anna had had her entire life turned upside down. She had been left with infant children in a state of absolute destitution and with no idea of the whereabouts of her husband. Their beautiful home at 18 Park Place, Cheltenham, built only a few years previously, had to be sold at auction in order to try to settle Cox's debts. Anna and her children had to go to live temporarily with an aunt who ran Yearsley's Hotel on the High Street in Cheltenham. Francis Joyce's lover Miss Yearsley was undoubtedly connected with the family who ran this hotel. [12] In a lovely gesture the local community rallied to Anna's aid, with the Cheltenham Chronicle organising an appeal in January 1836 to raise money for her and the children. The aim of the appeal was to generate enough funds to establish Anna in some sort of a business venture, giving her the ability to provide for herself and the children. [13]

Francis Joyce would obviously have known of the losses and heartaches that Ellen and her immediate family had suffered in the year before he left her, with the deaths of her father and sister. He would have seen the devastation caused to Anna by her husband's desertion, and yet he still left and despite impassioned pleas refused to return.

Mr Morris and Sir John Campbell

Ellen probably returned directly to Bath after leaving Southampton; I think it is most likely that she went and stayed initially with her sister Sophia Ann and her family at their home on Daniel Street, Bath. At some stage Ellen made the understandable decision to present herself to society as a widow and adopted the surname Bayly, which was her mother's maiden name. [14] Around twelve years after leaving Southampton and despite the hardships she undoubtedly suffered by the desertion of her husband, Ellen had made an extremely comfortable home and life for herself at South Bank Villa, Weston, Bath. She had the house, one male and two female servants and could even afford to run a one-horse chaise. Intriguingly, she also lived for part of each year in a house with servants and a pony-chaise in affluent Conduit Street, off Bond Street in Mayfair, London. [14] She had a yearly income of one-hundred and eighty pounds, which was most probably an inheritance from her parents, and whilst this was a respectable amount of money it was clearly not enough to enable Ellen to lead this sort of lifestyle unaided; her lodgings in London alone were one-hundred and fifty pounds per year.

As the reign of Queen Victoria progressed a new Act of Parliament was introduced in the United Kingdom known as the Matrimonial Causes Act 1857. This act enabled a couple to apply for a divorce in the civil courts, rather than through a costly Private Act of Parliament. It very much favoured a male applicant as a husband needed only to cite adultery by his wife as a cause for divorce, whereas a woman had to prove that her husband had not only committed adultery but also additional transgressions such as cruelty, desertion or incest. Throughout the years since his disappearance to France Ellen had heard absolutely nothing from Francis Joyce, and so on 30 July 1863, some twenty-six years since he had left her, she submitted a petition for a divorce by reason of his adultery coupled with his desertion of her. She stated during the proceedings that she had not applied sooner as she had not been aware of the change in the law until friends brought it to her attention. [11]

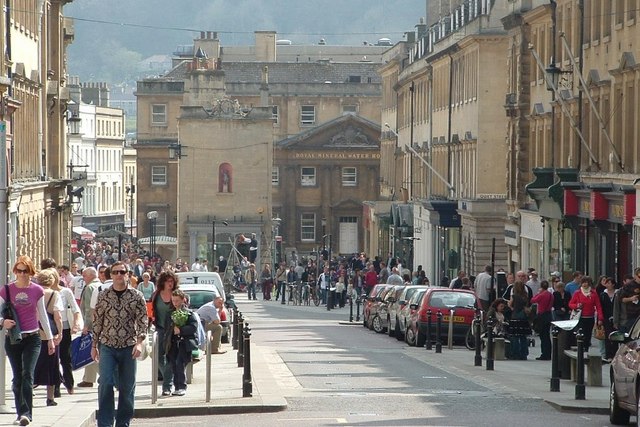

Photograph showing Milsom Street, Bath, where Ellen's friend Frederick Morris lived and worked as an upholsterer and auctioneer. Donnylad Creative Commons Attribution Share-alike license 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Once Francis Joyce's whereabouts were established, Ellen's solicitor, Edward Bromley, needed somebody to travel to France with him in order to provide a formal identification of Joyce. This clearly needed to be somebody who had known him back in 1837. Ellen's widowed brother-in-law Charles Morris had a brother named Frederick (b.a.1808-1875), who worked as an Auctioneer and Upholsterer on Milsom Street, a street filled with elegant Georgian town houses in Bath. The Morris family had been friendly with Ellen's extended family for many years, Frederick had known Ellen since they were both about twelve years old and he managed her family's financial affairs from the mid 1840s. Frederick and Ellen developed a close friendship, especially in the years following her sister Louisa's untimely death. Her children were Frederick's and Ellen's nieces and they met frequently to discuss their welfare. Frederick Morris married twice. His first marriage was in 1831 to Julia Stafford (1808-1850). Very sadly Julia died following childbirth in 1850, leaving Frederick with five young children including a new-born. His second marriage six years later was to Cecilia Byron Harper (1827-1887). Cecilia and Frederick went on to have a further five children together. It was Frederick Morris who rather reluctantly agreed to go to France with Mr Bromley as there was apparently no-one else who could fulfil the role.

Morris and Bromley travelled to the city of Quimper where they located and identified the somewhat shocked and startled Francis Joyce. He confessed to leaving Ellen, living with another woman and having three children with her. The following day, in a state of great agitation, Joyce went to Frederick Morris' hotel room to implore him to use his influence with Ellen to beg her not to proceed with the divorce petition as it would cause great distress to their families and would be the ruin of him. He said that in his old age he was being visited for the sins of his youth. Francis was distraught and panicked at the realisation that his secret life would soon be all too public, however he eventually agreed to make an official declaration of the true facts and wrote letters accordingly; I wonder if the children had known the truth of their parents' relationship.

It would be reasonable at this point to assume that, as her husband had written to the court admitting both his adultery and desertion, Ellen was granted her divorce. Regrettably, this was not to be the case. Witnesses came forward to accuse Ellen herself of adultery, both with Frederick Morris and with a gentleman named Sir John Campbell. The court heard testimony from some of her former servants who had worked for her whilst she lived at South Bank Villa, regarding her supposed adultery with Frederick Morris. Servant Elizabeth Ponter stated that she had entered the dining room on one occasion and found Ellen rising from the sofa with her dress disordered and Frederick standing, straightening his clothing. A former housemaid, Lucy Webb, told the court how she and another servant had been listening at the parlour door once and overhead conversation and the creaking of furniture that led them to believe adultery had been committed. Several other servants apparently gave similar testimony. [15] Frederick Morris strongly denied any impropriety with Ellen and Ellen denied having a relationship with Frederick. Whatever the truth of their situation the events described by the servants reputedly took place between 1851 and 1853, a period during which Frederick was a widower and Ellen, as we know, had been abandoned by her husband.

Intriguingly, Ellen did admit to having an adulterous relationship with Sir John Campbell. [10] It would seem that the London house on Conduit Street was paid for by Sir John, who would apparently call there to visit with Ellen on an almost daily basis. I suspect that he was most probably Sir John Campbell K.C.T.S. (1780-1863) who had been an army officer in the Portuguese Service. [16] He had married his second wife Harriet Maria Meadows in 1842, and lived at 51 Charles Street, Berkeley Square, London, approximately seven minutes walk from Ellen's London residence in Conduit Street. Most disastrously for Ellen, this admission of her adultery with Sir John Campbell resulted in her divorce petition being dismissed. It is almost inconceivable to our modern minds that two people such as Ellen and Francis Joyce, who clearly had lived completely separate lives in different countries for thirty years, were forced to remain technically married to each other.

Postscript

The former Royal Hotel on Hayling Island photographed in 2014. Ellen's house Lennox Lodge is no longer in existence but was located near to the Royal Hotel. © Robin Webster, licensed for reuse under Creative Commons Licence ShareAlike 2.0 Generic

In the years following the court case Ellen left England and lived for some time in the popular bathing resort of Boulogne-sur-Mer in the north of France, where she continued to live under the surname Bayly. [17] She returned to England towards the end of her life and purchased Lennox Lodge on Hayling Island in Hampshire. Described in 1875 Hayling Island was then "a quiet watering place on the South Coast, two-and-a-half hours from London by railway ...... bathing on four miles of splendid beach, and there is a good hotel - The Royal.", [18] Lennox Lodge was situated in South Hayling, right at the bottom of the island on the sea front, and would have afforded Ellen magnificent views across the Solent towards the Isle of Wight. Set in over three acres of land, the house had a dining room, drawing room and library, four bedrooms, a dressing room and four servants rooms, a kitchen, housekeepers room and offices. Outside was a double coach house, a stable with three stalls and a harness room. [19] Ellen clearly lived in some comfort in the house, which was situated near to the Royal Hotel, a Grade II listed building built around 1826. Ellen died at the age of sixty-six on 27 March 1876 at St George's Hospital, Hyde Park Corner, London. A year later on Thursday 19 April 1877, her household possessions were sold at auction. Amongst her effects were valuable oil paintings and engravings, and specimen orange trees and 'choice plants'. [20]

There is a rather interesting postscript to Ellen's life. As previously mentioned her brother William Hawkins Cox fled to America in 1835, leaving behind his wife Anna and eight children. At the time of his father's disappearance their eldest son William Henry had been away at sea serving as a Midshipman on board the ship the John Cootes in Bombay and China. He arrived back home to Cheltenham to the awful discovery that his father had left the country abandoning his mother and siblings. William Henry, aged about seventeen years old, had immediately set out to try to find his father in America. He eventually succeeded in finding him working for the Morning Chronicle in Pennsylvania and sent word home to Anna in England. Despite, or maybe because of, the fact that her husband had run away and left her in the most dire financial circumstances, Anna and the children went out to join him in Philadelphia in 1838. They all assumed the surname Crump, and Anna even went on to have two more children with him. William Hawkins and William Henry became Joint Editors of the Pennsylvania Inquirer newspaper and worked together until about 1848. After his father's death in 1862 William Henry worked as a builder in various cities in America; his younger brother, John Crump (1827-1892), was a renowned builder and architect responsible for buildings such as the Third Chestnut Street Theatre in Philadelphia constructed in 1862.

Following Ellen's death her solicitor, Edward Bromley, placed an advertisement in the Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette on 22 February 1877. It asked for her brother William Hawkins Cox and any of his children to contact him, as they would hear something to their advantage. William Hawkins had actually predeceased Ellen, however word that he was being looked for somehow reached William Henry in America. He made contact with Mr Bromley, returned to England and in February 1879 successfully established his identity in court as Ellen's nephew. [12] He inherited her home Lennox Lodge on Hayling Island. Five months later William Henry Cox married his cousin, Louisa Frances Morris, daughter of Ellen's sister Louisa. William Henry and Louisa moved in to Lennox Lodge following their marriage and remained there until their deaths in the 1890s.

References

- ^ Salisbury and Winchester Journal 6 July 1829

- ^ The National Archives of the UK; Kew, Surrey, England; General Register Office: Birth Certificates from the Presbyterian, Independent and Baptist Registry and from the Wesleyan Methodist Metropolitan Registry; Class Number: RG 5; Piece Number: 39

- ^ London Evening Standard 26 September 1829

- ^ The National Archives of the UK; Kew, Surrey, England; General Register Office: Birth Certificates from the Presbyterian, Independent and Baptist Registry and from the Wesleyan Methodist Metropolitan Registry; Class Number: RG 5; Piece Number: 29

- ^ Kidd's Picturesque Pocket Companion to Southampton etc published by W Kidd, Chandos Street, West Strand and Francis Joyce and Co, 169 High Street, Southampton 1830

- ^ Hampshire Telegraph and Sussex Chronicle etc (Portsmouth, England), Monday, July 6, 1829

- ^ Hampshire Advertiser: Royal Yacht Club Gazette, Southampton Town & County Herald, Isle of Wight Journal, Winchester Chronicle, & General Reporter (Southampton, England) Saturday, December 18, 1830

- ^ Hampshire Advertiser 29 April 1837

- ^ Berkshire Chronicle 25 February 1837

- ^^ Western Daily Press 09 June 1865

- ^^ Morning Post 6 February 1864

- ^^^ Cheltenham Mercury 8 February 1879

- ^ Cheltenham Chronicle 28 January 1836

- ^^ Western Daily Press 9 June 1865

- ^ Morning Advertiser 08 June 1865

- ^ Oxford DNB H. M. Chichester, ‘Campbell, Sir John (1780–1863)’, rev. Gordon L. Teffeteller, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004

- ^ England & Wales, National Probate Calendar (Index of Wills and Administrations), 1858-1966

- ^ Hampshire Advertiser 24 March 1875

- ^ Hampshire Telegraph 16 May 1877

- ^ Hampshire Telegraph 07 April 1877