Proprietors of Punch Magazine

Early Days

'Once upon a time a wind shook an acorn to the ground. The swine were munching their meal; thousands of acorns were swallowed. But this one acorn fell into a nice soft piece of earth; and the dews fell upon it, and in a brief time it seemed to open its mouth, and then it said - "I am now but an acorn; but I will grow into a huge oak; and I will become a part of a ship that shall sail to all corners of the world, bearing about all sorts of good things in my hold; and carrying the white flag of peace at my masthead to all nations." Now this acorn was Punch

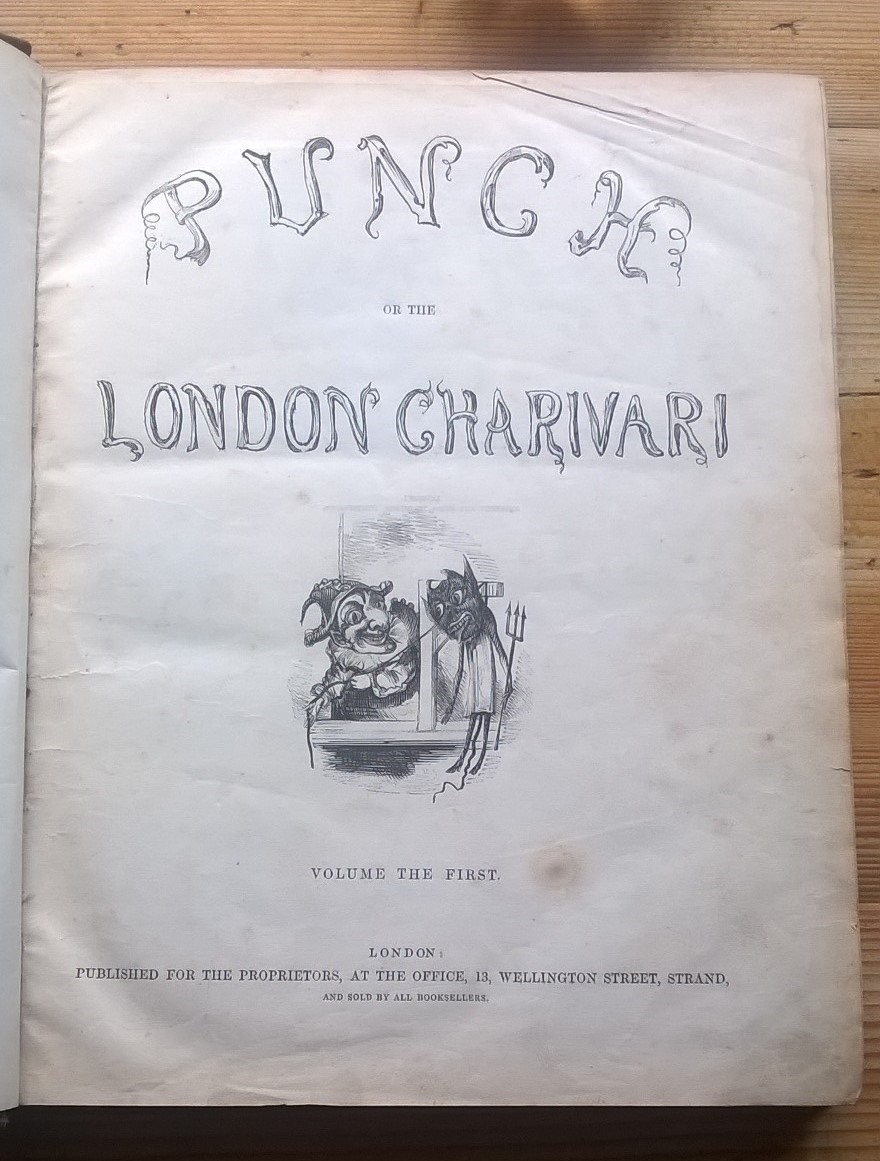

Title page illustrated by William Walker Newman from the first volume of Punch published from 13 Wellington Street, Strand in 1841 and printed by Bradbury and Evans.

Christmas 1842 marked the beginning of a momentous chapter in the lives of William Bradbury and Frederick Mullett Evans as they became the sole proprietors of the weekly satirical magazine Punch, or The London Charivari. Speaking twenty-six years later of Mark Lemon (1809-1870), Punch's first editor from its inception until his death in 1870, Frederick Mullett Evans remarked:

"It was Uncle Mark who was the chief conspirator when they brought Punch to Whitefriars; it was his eloquence alone that induced us to buy Punch." [2].

Punch, first published on Saturday 17 July 1841, ran continuously for one-hundred and fifty-one years until 8 April 1992. It had a relaunch by businessman Mohamed Al-Fayed on 6 September 1996 before finally ceasing publication on 28 May 2002.

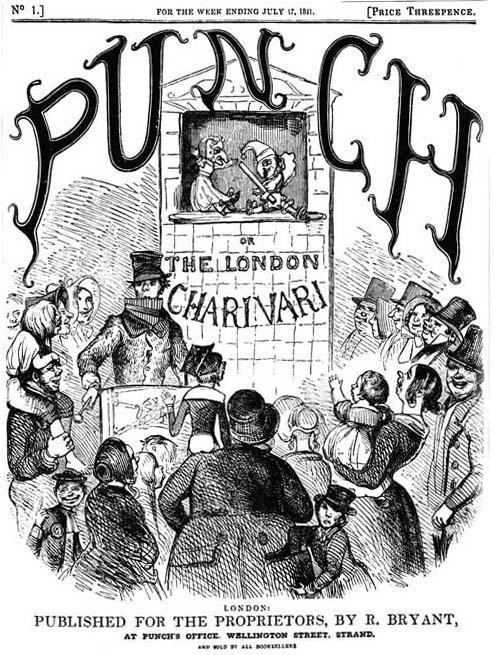

The details of the initial proposals for the comic magazine are somewhat murky and slightly lost in the mists of time. It would appear though that the idea for what would become Punch had first been formulated by the engraver, Ebenezer Landells (1808-1860), a friend of his, Joseph William Last (1809-1880), who was a printer from Woolverstone, Suffolk, [3] living and working at 3 Crane Court, Fleet Street, and the journalist and playwright Henry Mayhew (1812-1887), friend of Last and son of his solicitors. Ebenezer Landells discussed with Joseph Last the idea of producing a comic magazine in London which would have a similar flavour to the satirical Parisian magazine, Le Charivari, published since 1 December 1832 by the French caricaturist Charles Philipon (1800-1861). Last, liking the idea, introduced Landells to his friend Mayhew who immediately saw a future in the proposal. Mayhew, in turn, contacted his friend Mark Lemon (1809-1870). Recently married and with a young son, Lemon had no steady income at the time; he was writing sketches, verses and plays with some successes and had latterly been in charge of the 'Shakespeare's Head', a public house on Wych Street, Drury Lane, frequented by writers, actors and artists. The position at the tavern proved to be fairly disastrous however and Lemon was dismissed; by the spring of 1841 Mark Lemon, his wife Helen (Nelly) and son Mark were living at 12 Newcastle Street, Strand in a house shared with thirteen other people. [4] Henry Mayhew and Joseph Last met with Mark Lemon at Newcastle Street and names of potential writers and artists for the new publication were discussed. Further meetings took place at the 'Edinburgh Castle' tavern on the Strand, the 'Crown Inn', Vinegar Yard on the south side of Drury Lane Theatre and at Ebenezer Landell's home, 32 Bidborough Street, St Pancras. Ultimately a staff was assembled; joint editors were to be Mark Lemon, Henry Mayhew and Joseph Stirling Coyne (1803-1868) an Irish humourist and playwright; the main cartoonist was to be Archibald Henning (1805-1864), son of Scottish sculptor John Henning (1771-1851); writers approached included Douglas Jerrold (1803-1857), William Henry Wills (1810-1880) and Gilbert Abbott a Beckett (1811-1856); with Landells as engraver and Last as the printer. The magazine was initially to be published from Wellington Street (South), Strand by Richard Bryant (born circa 1803).

A name for the periodical was needed and again the exact details of how Punch came to be chosen have been lost over time. One account states that at a meeting someone said that the paper, like a good mixture of punch, was nothing without Lemon. Mayhew reportedly seized upon this idea and cried out "A capital idea! We'll call it Punch!", however other sources dispute this version of events. Whatever the truth, Punch it soon came to be. Finally an agreement was drawn up and signed on 14 July 1841 between Henry Mayhew, Mark Lemon, Joseph Stirling Coyne, Ebenezer Landells and Joseph Last. Mayhew, Lemon and Coyne were to have a one third share in the magazine with Landells and Last holding the remaining two thirds.

Following a tense night of eager anticipation spent by the co-editors at Joseph Last's printing office on Crane Court, the first issue of Punch hit the news stands on Saturday 17 July 1841 and initial sales were encouraging. Reviewing this first issue the following day The Sunday Times said:

"We heartily wish it success. Mirthful without malice, witty without grossness, and pointed without partisanship..."

However, despite this initial promise, business quickly slumped. Indeed things soon reached such a parlous state that had Mark Lemon not sold a drama of his for thirty pounds and given the money to the publisher then the third copy of Punch would not have been produced. [5]

Front cover of the first edition of Punch magazine published on 17 July 1841. Image taken from M.H. Spielmann The History of Punch courtesy of http://www.gutenberg.org/

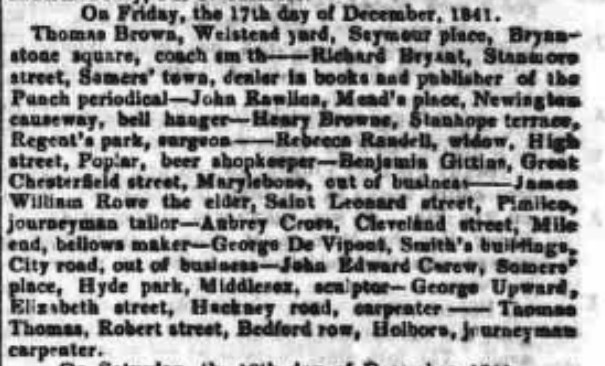

Click to enlarge. Screen shot taken from Bells New Weekly Messenger 12 December 1841, showing Richard Bryant publisher of Punch as an insolvent debtor, to be brought before the Court at Portugal Street, Lincoln's Inn Fields on Friday 17 December 1841.

The choice of Bryant as Punch's first publisher is an interesting one, shrouded, as with so much to do with the start of Punch, in mystery. Examination of the very first Punch cover together with the original prospectus reveals that Punch was to be published for the proprietors by R Bryant at Punch's Office Wellington Street, Strand. Several sources however [6] state that the publisher was W Bryant, with one source [7] naming this Bryant as William Bryant. Investigating this anomaly I found that an 'Insolvent Debtor' named Richard Bryant of Stanmore Street, Somers' town, described as a "dealer in books and publisher of the Punch periodical" was ordered to be brought up before the Court at the Court House, Portugal Street, Lincoln's Inn Fields on Friday 17 December 1841. [8] Exploring this further I found that Richard Bryant had actually been sent to the Whitecross Street debtors prison on Wednesday 4 August 1841, less than three weeks after the publication of the first copy of Punch. [9] Intriguingly, during a lecture given by Punch's editor Shirley Brooks (1816-1874), he said:

" At first, the paper was published by a person who was noted as being connected with some disreputable prints, and there was an ill-odour resulting from the connection hanging about Punch. This was no fault of the projectors; and the moment they were aware of the fact, they took the paper to a respectable firm, who became the proprietors." [10]

Tracing Richard Bryant back in his career I have found no evidence of him being connected to "disreputable prints" but found that he was a law bookseller and publisher, who in 1830 was living at 59 Carey Street, Lincoln's Inn Fields. [11] As the 1830s progressed he lived in the same environs at Tooks Court and later at Breams Buildings before moving to Stanmore Street. [12] It is interesting that a law bookseller and publisher was chosen as publisher and I wonder if Richard Bryant was known to Henry Mayhew's brother and father, Joseph Last's solicitors, who were working from offices at 26 Carey Street, Lincoln's Inn Fields. Following his release from the debtors prison Richard found work as a Clerk to the Smithfield Market Association [13] before his death in 1858 at the age of fifty-five. [14] I think it is likely that the "ill-odour" around the association of Punch with Bryant that Shirley Brooks spoke of would be connected with his insolvency.

The agreement signed on 14 July 1841 said regarding Bryant:

"That the publisher for the time being of the said work shall be the person by whom all Sales of the same Work shall be made and who shall receive all monies in respect of such Sales but all such Sales shall be made on account of the persons parties hereto proprietors of the said Work and all accounts against debtors shall be sent in and delivered to them as being indebted to the said proprietors."

It also stated that a meeting should be held at Mark Lemon's house at eight o'clock every Saturday evening and that:

" ....the publisher of the said Work and all other persons shall attend at such Meeting and bring all monies which may since the last Meeting have been received in respect of the sale of the same Work or otherwise on Account thereof and pay the same over to the parties constituting such Meeting and such parties shall out of such monies in the first place pay all expenses of Advertising, Cost of paper, salary to the publisher Rent of any premises necessary for conducting the said Work and all other incidental outgoings and expenses whatsoever which shall have been incurred in respect of the said Work and which shall have been duly audited and allowed as aforesaid (other than those which shall be payable to the parties hereto as such Editors Engraver or printer as aforesaid) and then in the next place in paying to the several persons parties hereto all their claims and demands in respect of the same Work as such Editors Engraver and printer as aforesaid." [15]

My reading of this is that Bryant was to take a salary from the proprietors for his part in the production of the magazine, and as sales were being made on account of Landells, Last, Lemon, Mayhew and Coyne debtors were indebted to them and not to Bryant, therefore any money from sales of the magazine should not have been affected by Bryant's insolvency. We do not know however how honest Richard Bryant was; he had a wife and three children under four years old at home. Were funds intended for the proprietors used to cover his mounting financial difficulties? Whatever the true impact of Bryant's financial situation the mere fact that their publisher was in the debtors prison just after the third issue had been produced must have caused enormous stress and consternation to the proprietors; as previously noted this third issue was apparently only saved by a cash injection from Mark Lemon. Bryant's role as publisher was marketing, circulation and accountancy, his loss would cause an unnecessary headache for the proprietors. Notwithstanding this turmoil Punch stumbled along through the early months. However by September 1841 the printer Joseph Last had reached breaking point and decided to extricate himself from the project. It was at this point that an approach was first made to Bradbury and Evans to try to persuade them to become Punch's new printers and purchase Last's interest in the magazine for one-hundred and fifty pounds.

The Transfer to Bradbury and Evans

In July 1841 forty-two year old William Bradbury and thirty-six year old Frederick Mullett Evans were printing from substantial premises at numbers 1-6 Lombard Street (now Lombard Lane), a cramped and narrow street leading off Fleet Street in the Whitefriars district of London. At this time they had six presses in the machine room under the supervision of George Gifford Beard, each machine requiring one man and two boys to operate it. [16] These steam presses with their roaring, thunderous engines ran continuously for twelve hours each day, from 8.00am to 8.00pm Monday to Saturday, with all-night working not a rare occurrence. A more detailed look at Bradbury and Evans' working practices can be found here. Over the eleven years of their partnership thus far Bradbury and Evans had acquired a reputation for reliability, efficiency and trustworthiness. At Lombard Street they had established a stereotype foundry enabling them to rapidly reproduce pages of type. They undertook intricate illustrated work for author Jane Webb Loudon (1807-1858) in 1841 when she edited the Ladies Magazine of Gardening, which was published monthly and illustrated with coloured plates and woodcuts; for gardener and architect Joseph Paxton (1803-1865) with The Horticultural Register and the exquisitely illustrated Paxton's Magazine of Botany and Register of Flowering Plants; and they printed all eleven volumes of poet and humourist Thomas Hood's Comic Annual, something of a precursor to Punch, from its inception in 1830. For a greater exploration of their early years see here. Significantly they were the printers of Charles Dickens' illustrated monthly publications for Chapman and Hall, and since the spring of 1840 had been successfully printing his weekly serial Master Humphrey's Clock. This weekly periodical was printed at Lombard Street on one sheet in Royal Octavo, a large sheet measuring 253mm x 158mm on which sixteen pages of letterpress were printed, the sheet then being folded three times to obtain eight leaves. Of the sixteen printed pages, twelve were to be Dickens' text and the remaining four were to be taken up with the title page and advertisements. It was also to be illustrated with woodcuts. Priced at three pence a copy Master Humphrey's Clock had the exact same price and composition that Punch was to have.

Despite initially agreeing to the proposal to buy Joseph Last's share of Punch for one-hundred and fifty pounds, Bradbury and Evans soon changed their minds and withdrew from the negotiations, stating that their involvement: "would involve them in the probable loss of one of their most valuable connections." [15] Ultimately Ebenezer Landells bought out Joseph Last, after which printing was carried out briefly by Charles Mitchell of Red Lion Court, Fleet Street and then from 11 Crane Court, Fleet Street by Samuel Mills, formerly of the printing firm of Mills, Jowett and Mills. A few years after he had first arrived in London with his brother-in-law William Dent, William Bradbury had rented a room from Mills, Jowett and Mills at Bolt Court. Sadly however Mills, Jowett and Mills were declared bankrupt in 1834. The Times newspaper of 18 November 1834 carried a report which stated:

"The failures of the parties in this case excited great surprise, inasmuch as they were in a large and it was thought flourishing way of business. They were the successors of Mr. Bensley in the conduct of the extensive printing establishment in Bolt-court. At the first meeting to-day 16 proofs of debts were tendered and admitted, amounting to 14,322l. 19s. 9d."

Following the bankruptcy it would appear that Samuel Mills and his son established another printing business in 1836 in Gough Square, before Samuel Mills senior moved to 11 Crane Court, Fleet Street becoming a neighbour of Joseph Last.

By October 1841 further deliberations had taken place with Bradbury and Evans; an agreement had been drawn up between Landells, Lemon, Mayhew and Coyne and Bradbury and Evans stating that in consideration of a loan of one-hundred and fifty pounds the printing of Punch would be assigned solely to them. By the end of 1841 Bradbury and Evans were indeed the printers of Punch and the magazine limped along. In November 1841 Landells, Mayhew, Lemon and Coyne tried again unsuccessfully to convince Bradbury and Evans to buy Punch for five-hundred pounds. [17] This proposal proving ineffectual, Mayhew, Lemon and Coyne transferred their one-third ownership of Punch to Ebenezer Landells on 6 December 1841, making him the sole proprietor by the dawn of 1842. However as the year progressed into summer Bradbury and Evans were finally persuaded to invest capital into the magazine. In an agreement dated 25 July 1842 Bradbury and Evans acquired two-thirds of Landells' share of Punch. Matters were not cordial however between Bradbury and Evans and Landells; it appears that Bradbury and Evans were not paying Landells either for his work on the magazine or his third of the profits of the business. Over the course of 1842 letters were exchanged in which Landells became increasingly disconsolate at this lack of payment. Eventually on 29 December 1842 Landells signed his remaining interest in Punch over to Bradbury and Evans for three-hundred and fifty pounds, an amount which according to Punch writer George Hodder saved the magazine from bankruptcy. [18]

In the midst of the economic gloom surrounding these early Punch months, the one great commercial success was an idea devised by Henry Mayhew for an Almanack which was to be brought out on 1 January 1842. Advertisements enthusiastically proclaimed that it was to be:

"Illustrated with Fifty Humorous Cuts of the World as it is to be in 1842. It will also be enriched with FIVE HUNDRED ORIGINAL JOKES! at the irresistibly comic Charge of THREE-PENCE" [19]

This Punch Almanack was written by Henry Mayhew and Punch writer Henry Willoughby Grattan Plunkett aka H P Grattan (1808-1889). The authorship, incredibly, took place over seven days and nights at the Fleet Prison where Grattan was being held as a prisoner for debts. Mayhew apparently bribed the guards to allow him to stay with Grattan until the work was completed as later remembered by Grattan:

" It was against the rule for any person , not having a legal right, to sleep in Her Majesty’s establishment; but, and not for the first time, the rights of the Crown were superseded by half-crowns properly and judiciously administered to the turnkey on duty, and for seven days and nights Mayhew was a voluntary prisoner; and during that festive period the first Punch 'Almanac' was begun and finished by both of us" [20]

The Almanack was an unbelievable success and Bradbury and Evans' presses had to cope with demand that saw sales rise from their usual few thousand to somewhere around ninety-thousand copies. [15] The extraordinary triumph of the Almanack induced the proprietors to alter the format of the magazine slightly by discarding two pages of advertisements in order to make room for a greater quantity of material and improved illustrations. [21] The workers in the machine room, under the supervision of George Gifford Beard, were used to intense, high pressure, high volume work. Bradbury and Evans were the sole printers in London of Chambers's Edinburgh Journal for the publisher William Somerville Orr and in 1841 they were printing some forty-thousand sheets of the Journal per week. [22] Work for Charles Dickens also stretched the presses and the workers with sales of the last parts of the serial The Old Curiosity Shop, published in Master Humphrey's Clock, reaching one-hundred thousand. [23]

Building a Brotherhood

Bradbury and Evans' arrival as proprietors brought about a gradual change in personnel at the periodical. They were business minded individuals keen to put the magazine on a sound financial footing. Bradbury in particular, described as "the keenest man of business that ever trod the flags of Fleet Street" was a quiet, careful man who had worked his way up from a printer's apprentice in Lincoln to the partnership with Evans. Under their management a nucleus of writers and illustrators were brought together. Mark Lemon was appointed as sole Editor, with Henry Mayhew moved to the role of Suggestor-in-Chief. Joseph Stirling Coyne left Punch when the transfer to Bradbury and Evans took place, he left under a cloud with Mark Lemon being extremely troubled by him plagiarizing work from a newspaper. [7] Politically liberal-minded Douglas Jerrold continued as a Punch writer under Bradbury and Evans proprietorship, acting as second-in-command to Mark Lemon. Having served in the Navy at the age of ten under the command of Rear Admiral Charles Austen (1779-1852), Jane Austen's youngest brother, Douglas was apprenticed to a printer following his family's move to London in 1816. A slight, stooped figure he had a biting, satirical wit with fiercely radical views; he wrote his first piece for Punch in the second number and then wrote continuously for the magazine until his sudden death in 1857. Writer Gilbert Abbott a Beckett, whose ancestors professed to have descended from St Thomas a Beckett, was an abundant Punch columnist, writing from the very first number until his sudden death from typhoid fever in 1856. Satirist and good friend of the illustrator John Leech and of Gilbert Abbott a Beckett, Percival Leigh, known as 'The Professor', was another prolific contributor from the first issue. Novelist and school friend of John Leech, William Makepeace Thackeray made his Punch debut in 1842. In a letter to his mother in June 1842 he was somewhat sniffy about the new periodical:

"I've been writing for the F. Q. and a very low paper called Punch, but that's a secret - only it's good pay, and a great opportunity for unrestrained laughing sneering kicking and gambadoing." [24]

His first writings for Punch were a series of satirical sketches known as Miss Tickletoby's Lectures on English History, however these were to be short-lived. In a letter to Bradbury and Evans dated 27 September 1842 Thackeray wrote:

"Your letter, containing an enclosure of £25, has been forwarded to me, and I am obliged to you for the remittance. Mr. Lemon has previously written to me to explain the delay, and I had also received a letter from Mr. Landells, who told me, what I was sorry to learn, that you were dissatisfied with my contributions to "Punch." I wish that my writings had the good fortune to please everyone; but all I can do, however, is to do my best, which has been done in this case, just as much as if I had been writing for any more dignified periodical."

This letter is interesting as it shows that Bradbury and Evans were clearly seen as the proprietors some three months before they had full control of Punch. In the early months of 1843 Thackeray's writing and drawings began to hit the right note with Bradbury and Evans and Mark Lemon and he too found a regular place on the Punch staff.

Archibald Henning who had designed and illustrated the first Punch cover left the staff in the summer of 1842. Artist William Newman (1817-1870), responsible for the title page illustration of the first volume, a modest and self-effacing man, continued to work for the magazine from the first issue until April 1850. He worked alongside artist Henry George Hine (1811-1895), a wood engraver who worked for Punch from September 1841 until 1844. The figure at the heart of the illustrators, however, was John Leech (1817-1864). Leech, a Charterhouse schoolfellow of Thackeray and a keen amateur artist, had originally studied medicine at St Bartholomew's Hospital, London where he befriended fellow student and future Punch writer Percival Leigh. Following his father's bankruptcy when John was eighteen years old he left medicine and turned to his love of drawing as a means to make money. Leech's association with Punch did not get off to the most auspicious start. He was commissioned to draw Punch's Pencillings for the fourth number of Punch to be published on 7 August 1841. However due to his poor time management his drawing on a block of wood was sent to the engraver too late for it to meet the publication deadline. This had serious knock-on effects for that issue of Punch, which appeared late and suffered a drop in circulation as a result. [25] Given a second chance though Leech soon became a Punch regular and his illustrations a firm favourite with the Punch readership.

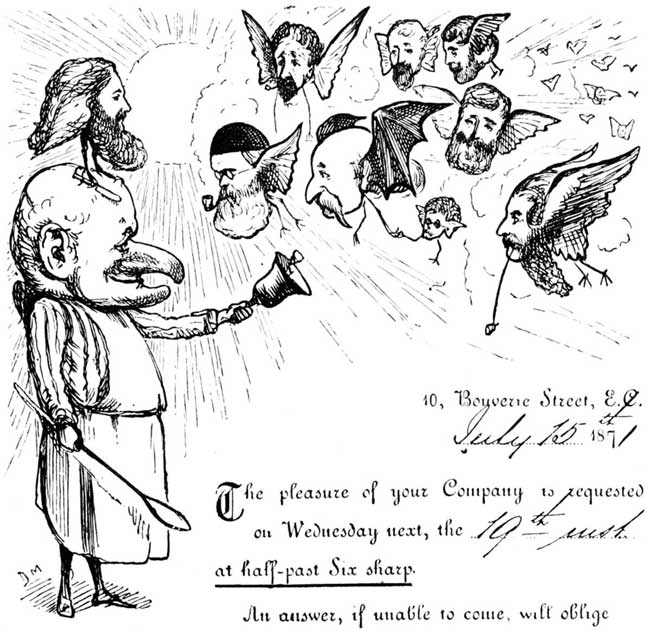

An invitation to attend the Punch weekly dinner. Drawn by George du Marier. Image taken from M H Spielmann A History of Punch 1895.

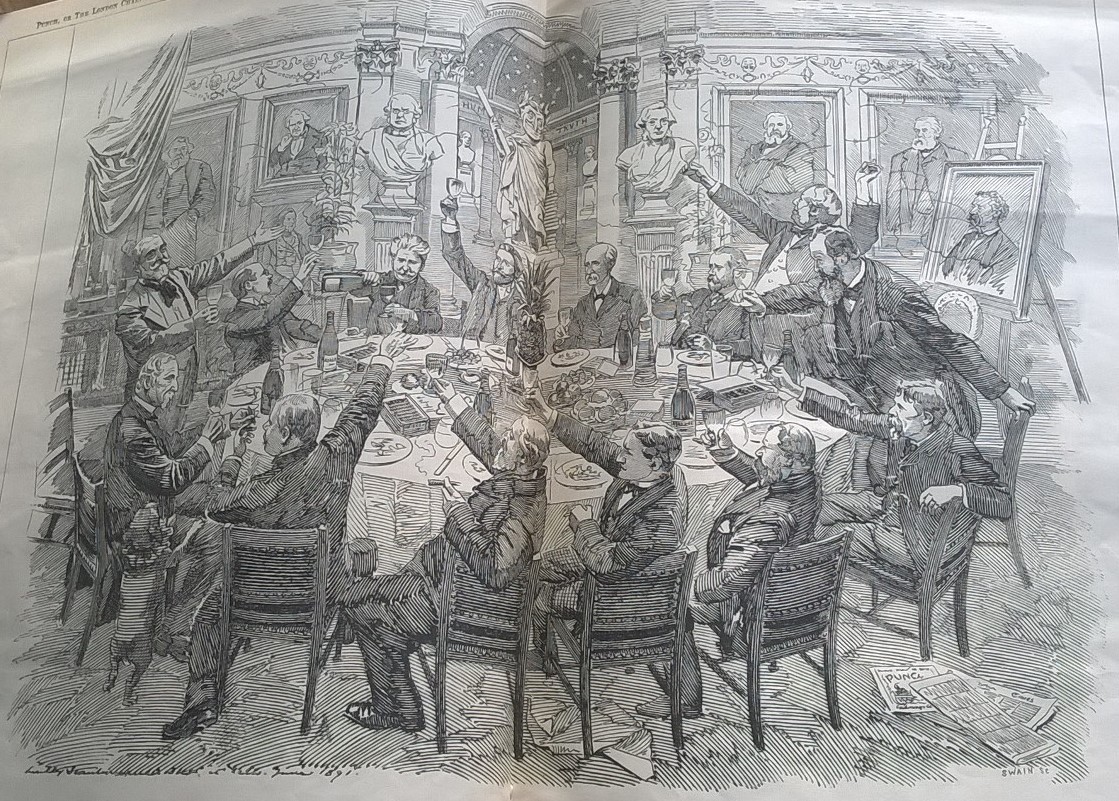

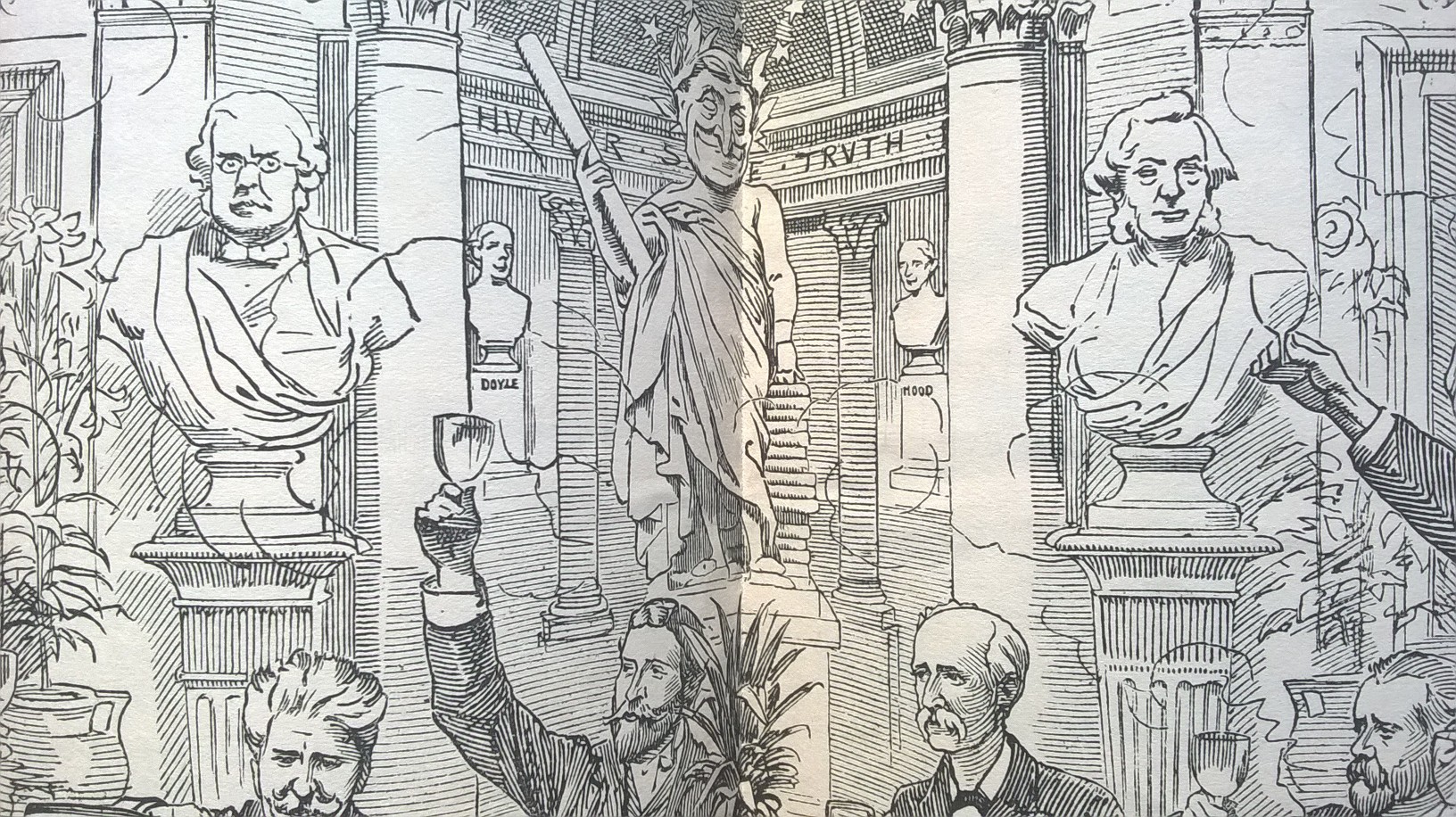

Click to enlarge. 'The Mahogany Tree'. Illustration of the Punch dinner table with staff toasting Mr Punch and celebrating 50 years of the magazine in July 1891. Drawn by Edward Linley Sambourne. The portrait hanging on the wall on the far left is of first editor Mark Lemon, and the busts displayed either side of Mr Punch are of Frederick Mullett Evans to the left as we look and William Bradbury to the right.

Click to enlarge. Detail from Edward Linley Sambourne's illustration 'The Mahogany Tree', showing the statue of Mr Punch, with the bust of Frederick Mullett Evans on the left and William Bradbury on the right. Busts of two other Punch contributors can be seen in the alcove, illustrator Richard Doyle and writer Thomas Hood.

In these early Punch days a tradition evolved that was to last for more than one-hundred years. The somewhat ebullient and lively men of Punch would meet weekly, at first on a Saturday evening and after the transfer on a Wednesday evening, and in a congenial atmosphere over food and drink would debate, argue and joke over subjects such as politics, social issues of the day and business. Under Bradbury and Evans' steadying proprietorship these weekly meetings took on a more focused character where, following a 6.30pm dinner ideas for the 'Large Cut', the weekly full-page illustration with blank verso, were mulled over, sometimes argued over and eventually decided upon.

The first of these Punch dinners was held at the coaching inn the Belle Sauvage, on Ludgate Hill, London, just to the east of Fleet Street. [26] The proprietor at the time was John Price (1808-1858) who was the brother of William Bradbury's wife Sarah. At St Bride's Church, Fleet Street on 6 February 1836 John had married a young woman named Ann Nelson (1816-1888), whose family were well-known London coach operators with an office at 52 Piccadilly. Indeed the coaching business was headed by her paternal grandmother and namesake Ann Nelson (1770-1852), an awe-inspiring businesswoman who ran the Bull Inn, Aldgate; her son Robert Nelson, John Price's father-in-law, was the previous proprietor of the Belle Sauvage. The Times newspaper of Saturday 4 January 1834 carried a report of the bankruptcy of coffee house proprietor John Leech, the father of future Punch illustrator John Leech. It was reported in The Times that several other coffee house keepers in the area, angered by his decision to establish a supper room in what was a very competitive field, had gathered together at the Belle Sauvage and formed an idea to drive Leech senior out of business by refusing to deal with any tradespeople who supplied him. The Times newspaper of Monday 6 January 1834 carried a letter from Robert Nelson fiercely protecting the reputation of his inn, strongly denying that any such meeting ever took place at the Belle Sauvage:

"I state most distinctly, that no such meeting ever took place in my house, nor elsewhere that I know of."

His father's bankruptcy and all that entailed for the circumstances of his family was something that vexed Punch illustrator John Leech until his dying day. [27]

Following the transfer of Punch to Bradbury and Evans the weekly dinners were held at their offices at 11 Bouverie Street, Fleet Street, and later at their office at 10 Bouverie Street. Attended by invitation only the weekly Punch dinner soon took on the personality of a gentleman's club. The Times newspaper wrote on 27 December 1842:

"There is one thing, in addition to the cleverness of Punch, which has not a little contributed to its success, and that is the unvarying good humour and propriety which prevail in it, and the total exclusion from its pages of all that is gross, low or coarsely personal."

In stark contrast to this sentiment, talk around the Punch dinner table was frequently at the level of the 'naughty schoolboy' with horseplay and the regaling of smutty and coarse jokes. Their world was very much a masculine enclave. The dinners could become quite boisterous affairs; on one occasion after Bradbury had asked Evans to pass him a slice of pineapple, Evans decided instead to bowl a whole pineapple down the length of the table. Incredibly it managed to reach Bradbury without breaking a glass or plate! [28] The sheer quantity of food and drink at these dinners was quite astounding; one such menu consisted of turtle soup, salmon cutlet, cold beef, pineapple fritters, cheese, strawberries and cream, cherries, pineapple punch, champagne, sherry and claret. Douglas Jerrold apparently had his name and address written on a label which he would tie around his neck so that if the evening's events became too drink infused he would stand some chance of arriving safely to the correct home. [15] The banquet started early in the evening at 6.30pm and was usually conducted in a spirit of agreeableness and accompanied by storytelling and sometimes even singing; it was finished by 8.30pm. Once the meal was concluded, over the smoking of cigars the serious discussions of the subject matter for the 'Large Cut' would begin. These discussions could, and quite frequently did, continue late into the night.

The table at which these dinners took place is now housed in the British Library. Made from deal and oblong in shape, carved into its surface with a penknife are the initials of nearly every editor and member of staff who worked for Punch. Bradbury and Evans would sit either end at the head of the table and a special wooden armchair was provided for Mark Lemon as editor, which was then used by subsequent editors. In January 1847 The Mahogany Tree, a Christmas song written by Thackeray was published in Punch; the staff came to connect the sentiment of these lines with their weekly dinners. One verse reads:

Here let us sport, Boys as we sit; Laughter and wit Flashing so free. Life is but short- When we are gone, Let them sing on, Round the old tree.

At this time, as previously mentioned, Bradbury and Evans were printing, amongst other publications, Chambers's Edinburgh Journal for publisher William Somerville Orr. Orr was the London agent for the Scotland based Chambers brothers, and his agreement with them stated that he could distribute the Journal throughout the whole of England with the exception of some northern counties and also Berwick-upon-Tweed and Belfast, which were to be supplied from Scotland. [29] This extensive distribution network proved to be extremely valuable to Bradbury and Evans in these early Punch months. Orr arranged for copies of Punch to be supplied to booksellers and traders on a 'sale or return' basis, a somewhat risky strategy that paid off, and with this invaluable help from Orr sales began to increase. The partnership between Bradbury and Evans and Orr sadly ended acrimoniously. The London Gazette of 2 October 1846 gave notice of the dissolution of the partnership between the three parties; Orr had major financial difficulties and owed Bradbury and Evans about two-thousand eight-hundred pounds, he had also probably misled them into believing that he had a partnership with the Chambers brothers, rather than simply being their London agent. In a letter dated 25 September 1846 William Chambers wrote from London to his brother Robert and said:

"Having seen Evans by chance on the street, he told me that they did not claim upon us, but looked only to Orr who they consider has used them, very ill." [30]

A rather interesting anomaly at this time in Punch's early history is the presence of a Joseph Smith listed as Punch publisher from volume four through to the start of volume eight, covering the years 1843 to 1845. I can find very little information on him; on the 1841 census for England and Wales he was living on Caroline Street, Eaton Square in a house shared with five others. He appeared to be single, was thirty-five years old and working as a Clerk. He is first mentioned as publisher in Punch volume four where the fine print reads:

Printed by Messrs. Bradbury and Evans, Lombard Street, in the Precinct of Whitefriars, in the city of London, and published by Joseph Smith, of 16 Caroline Street, Eaton Square, Pimlico, at the office, No. 13, Wellington Street, Strand, in the precinct of the Savoy, in the county of Middlesex.

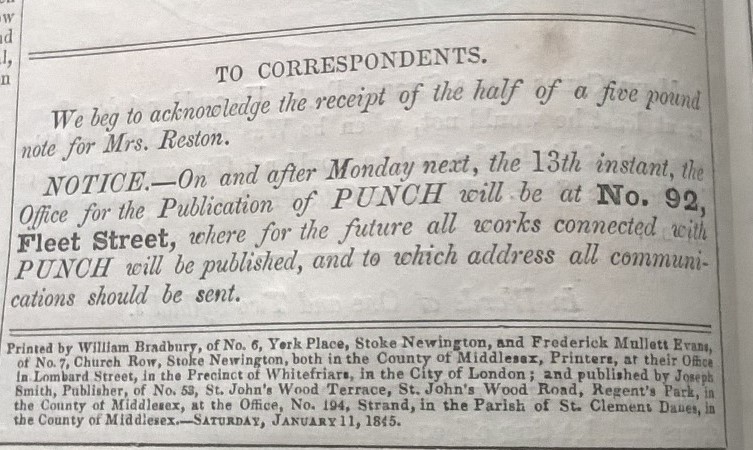

Click to enlarge. Notice placed in Punch Saturday 11 January 1845 announcing the move of the Punch office from 194 Strand to 92 Fleet Street, London. The small print contains the last mention of Joseph Smith as publisher.

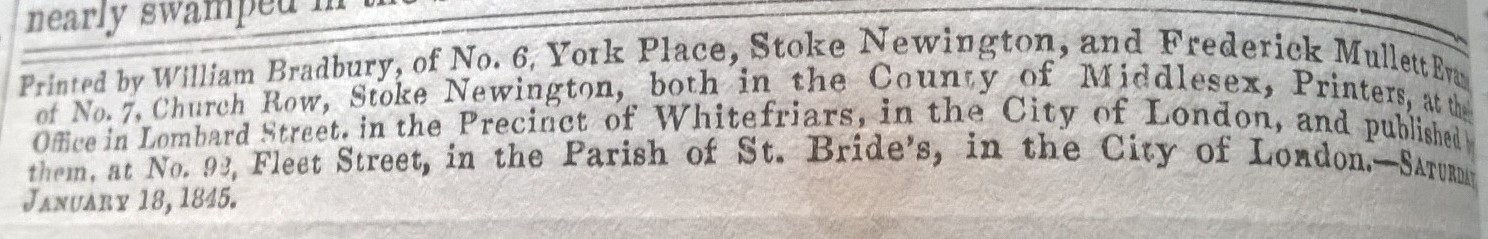

Click to enlarge. The first acknowledgement in print of Bradbury and Evans as both printers and publishers of Punch. Dated Saturday 18 January 1845.

The last acknowledgement of him as publisher is in the small print underneath a notice to correspondents dated Saturday 11 January 1845 announcing the move of the Punch office from 194 Strand to 92 Fleet Street, London on the following Monday. His address changed from Caroline Street, Eaton Square to 53 St John's Wood Terrace, St John's Wood Road, Regent's Park, London. The following week, Saturday 18 January 1845 was the first time in Punch that Bradbury and Evans were acknowledged as the publishers, despite having owned the publication since December 1842 and being recognised as the printers since 1841. I wonder if Joseph Smith worked for, or was known to, William Somerville Orr and was helping with the publication of Punch during this period that saw Orr heavily involved in the publication and distribution. However for lack of any further information Joseph Smith will have to remain something of an enigma at the moment.

During these early years Bradbury and Evans moved the location of the Punch office three times. As we have seen it began life at 13 Wellington Street (now Lancaster Place), just off the Strand, and remained there until May 1843. The site of this building is adjacent to the 'new wing' of Sir William Chambers' Somerset House on Lancaster Place which was added to the western edge of Somerset House between 1851 and 1856. In May 1843 the office moved around the corner and onto the Strand itself. The Punch issue for 13 May 1843 was published from this new location of 194 Strand situated opposite St Clement Danes Church. This was to be home until the beginning of 1845, when on 13 January the move was made eastwards along the Strand to 92 Fleet Street. This building was used for a year until the issue dated 24 January 1846, which stated that it was published from Punch's office at 85 Fleet Street. This was the address that was to be associated with Punch for the next fifty-four years. On Monday 19 March 1900 Punch was forced to move to 10 Bouverie Street, Fleet Street due to a road widening scheme that saw 85 Fleet Street purchased by the Corporation of London and the building subsequently demolished. [31]

The Song of the Shirt December 1843 - Esther's Story

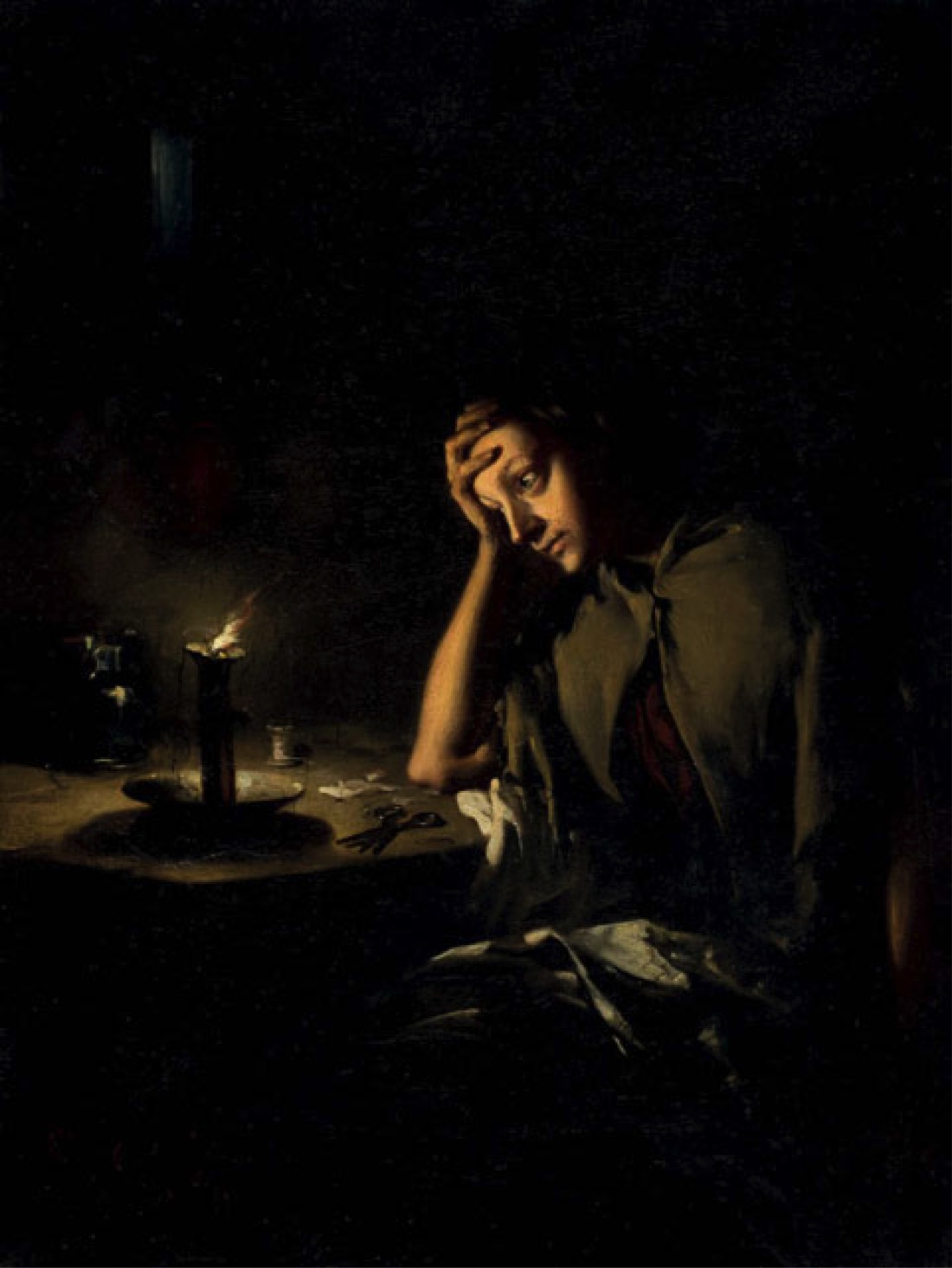

The Song of the Shirt by William Daniels (1813-1881), inspired by Thomas Hood's poem of the same name. 1875 Oil on canvas 43.5 x 34.5 cm (17 1/8 x 13 9/16 inches) Picture courtesy of The Crowther-Oblak Collection of Victorian Art and and the National Gallery of Slovenia and the Moore Institute, National University of Ireland, Galway via http://www.victorianweb.org/painting/daniels/1.html

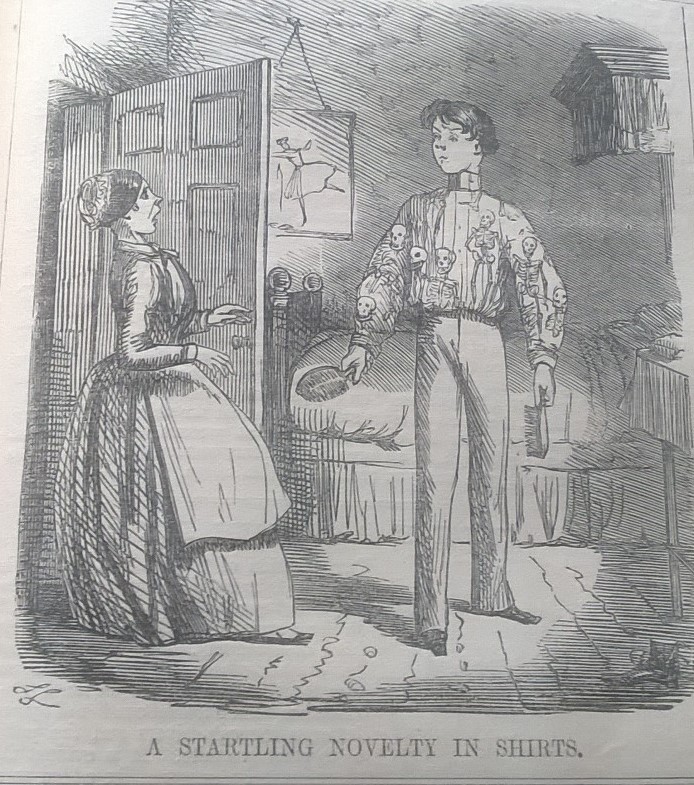

Click to enlarge. Illustration A Startling Novelty in Shirts by John Leech published in Punch in July 1853. The shirt, covered with skeletons, highlights the starvation wages paid to the seamstresses who made it.

Building upon information supplied in The Times newspaper of 27 October 1843, [32] it would seem that the young widow was a thirty-five year old woman named Esther Bedell (spellings of the surname vary) nee Rookwood, living on Well Street, Whitechapel in London's East End. [33] Esther's husband William, a thirty-nine year old mariner working on board the ship Mary at the East London Docks, had died on Friday 6 January 1843 from a fractured skull following a fall. Whilst lowering a bag of food supplies down the ship's hatchway he had slipped and fallen into the hold, banging his head hard against some timbers and knocking himself out. He actually survived the fall and did not appear to be too badly injured, so much so that he walked about three quarters of a mile to the London Hospital for treatment where his condition worsened and he tragically died two hours after arrival. [34] Distressingly, Esther was pregnant when her husband died; she gave birth to a son whom she named William Jeremiah after his father, on 5 February 1843, almost a month to the day after her husband's untimely death. [35] Living in a sparsely furnished room in a shared house in Whitechapel and desperate for money Esther began working for Henry Moses as a seamstress sewing shirts and trousers. However the income she received was a pittance, too inadequate to feed herself and her two children and in great distress she had pawned some of the garments which were the property of Mr Moses, whilst she continued to work on others. She was paid a meagre seven pence for each item of clothing that she made, out of which incredibly she had to buy the needles and thread to make them.

Following the Times article, Henry Moses wrote what he called a "justification" which was published in The Times on Tuesday 31 October 1843. In it he explained that his

"allowance for labour is considerably higher than many of the most respectable outfitting warehouses in this metropolis. The boys' trousers, for making which I paid the woman Bedell 7d per pair, I sell at 2s 9d, which the price of the material being deducted, leaves me a profit varying from 5 to 7 ½ percent."

In response The Times wrote:

"He may be, perhaps he is, the most liberal of all the slopsellers ..... but it is not less true that his profit, whatever may be its amount, is the result of his availing himself of the necessities of extreme poverty; that by how much his drudges receive less than an adequate return for their labour, by so much his profit is, morally speaking, unjustly acquired."

On 4 November 1843 under the heading "FAMINE AND FASHION", Punch reprinted The Times article concerning Esther's arrest, followed by an emotional outburst towards the slop-seller who would pay a worker the equivalent of one penny an hour. Typically women such as Esther would go to collect the materials to be sewn from their employers at around 4.00am or 5.00am and would then sew the garments together for anything up to eighteen hours each day. Before sending his poem to Mark Lemon, Thomas Hood had tried three other publishers who had all rejected it. As a last resort he contacted Lemon, with apologies that the subject matter would be ill-suited for use in a comic journal. He said that the poem could be thrown away if Lemon did not want it. Mark Lemon decided to publish it; the result was an absolute sensation. The circulation of Punch trebled and letters poured in to the editor. The poem was spoken of country-wide in newspapers, was translated into different languages, it was turned into songs, captured in paintings and turned into a play The Sempstress: A Drama by Mark Lemon. The dreadful plight of the working poor in England was highlighted. The opening stanza read:

"With fingers weary and worn, With eyelids heavy and red, A woman sat in unwomanly rags, Plying her needle and thread – Stitch! Stitch! Stitch! In poverty, hunger, and dirt, And still with a voice of dolorous pitch She sang ‘The Song of the Shirt!"

Later lines read:

"Work—work—work! My labour never flags; And what are its wages? A bed of straw, A crust of bread—and rags. That shattered roof—and this naked floor— A table—a broken chair— And a wall so blank, my shadow I thank For sometimes falling there!"

Conditions sadly continued to be utterly dismal for these poor families; writing 6 years later in November 1849 Henry Mayhew said:

"Still I was unprepared for the amount of suffering that I have lately witnessed. I could not have believed that there were human beings toiling so long and gaining so little, and starving so silently and heroically, round about our very homes." [36]

One seamstress said to Mayhew:

" "I live mostly upon coffee, and don't taste a cup of tea not once in a month, though I am up early and late; and the coffee I drink without sugar. Look here, this is what I have. You see this is the bloom of the coffee that falls off while it's being sifted after roasting; and I pays 6d. for a bagfull holding about half a bushel."

Ten years after The Song of the Shirt had been published Punch was still drawing attention to the plight of underpaid seamstresses with illustrations such as John Leech's A Startling Novelty in Shirts (shown above).

Tracing Esther through the records, it would appear that despite their appalling circumstances she and her little son William managed to survive. Esther continued working as a seamstress; almost twenty years after her arrest the 1861 census for England and Wales shows her working as a tailoress and boarding in a house at 69 Cartwright Square, Aldgate, Whitechapel with eight other people. It would appear that her living conditions sadly were as desperate as ever. In a letter written by John Liddle, Medical Officer of Health of the District of Whitechapel dated July 1875, Cartwright Square was listed among streets described as being of the most "wretched description" and

"that by reason of the closeness, narrowness, and bad arrangement, as well as by reason of the bad condition of the courts and houses within such area, diseases indicating a generally low condition of health amongst the population have been from time to time prevalent ; and the death-rate of such population has been excessive, such excess being more than 50 per cent, above the ordinary rate of the District of Whitechapel, of which it forms a part."

The 1871 census for England and Wales shows Esther living with her son William and his family. [37] William worked as a cooper, and he, his wife Ellen and young son William lived in Smith's Arms Place, St George in the East. There were eleven people sharing the same house. No occupation is given for Esther and I wonder if she was ill and unable to work and so had moved in with her son and his family. Tragically Esther committed suicide eight years later at the age of seventy-two. At the inquest it was revealed that she had been fearful of going blind and becoming a burden to her family. [38]

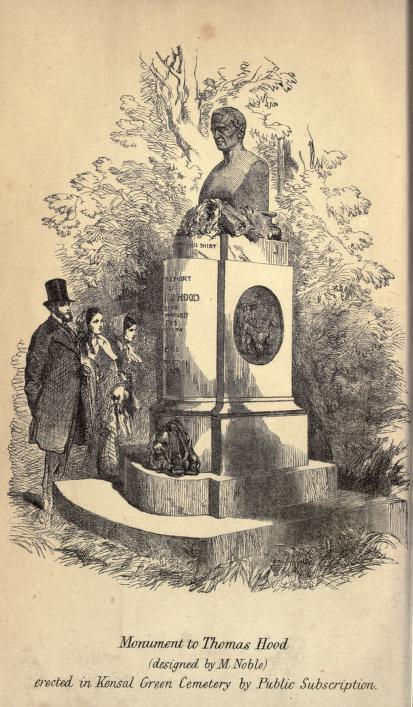

Illustration of the memorial erected to Thomas Hood in Kensal Green Cemetery in 1854. Illustration from Frontispiece to volume II of Memorials of Thomas Hood edited by F F Broderip and T Hood 1860. See https://archive.org/stream/memorialsofthoma02hooduoft#page/n9/mode/2up

The Song of the Shirt's author, the humourist and poet Thomas Hood, sadly died on 3 May 1845 a few days shy of his forty-sixth birthday following years of illness. Bradbury and Evans had printed his Comic Annual since its beginning in 1830, and he continued to write and submit several pieces of work for Punch until his death. Hood's personal finances had been in quite a parlous state near to his death, and he was buried on 10 May 1845 at Kensal Green Cemetery, London with no headstone to mark the site. More than seven years later in the autumn of 1852 writer Eliza Cook (1812-1889) raised the fact that Hood had no grave monument. In November 1852, under the title A Tomb for Hood, Punch published a poem about this lack of a tombstone; the opening verses read:

"GIVE HOOD a tombstone; -'tis not much to give To one who stirr'd so oft our smiles and tears; But why a tomb to him whose lines will live, His noblest monument, to after years? To which I answer, that in times to come- Times of more equal lots and gentler laws- The workers may not seek, in vain his tomb Who pleaded, once, so movingly their cause."

The Sunday Times of 7 November 1852 carried an article calling for the same, stating that a number of young men of the Whittington Club were hoping to raise a monument or statue to Hood by public subscription. This club, with premises on Arundel Street, Strand, had been founded by Punch writer Douglas Jerrold in 1847. It was begun with a library, reading, meeting and dining rooms for the lower middle classes such as clerks working at the Inns of Court, shop assistants and journalists, and most unusually for the times women were permitted to be full members.

Donations in Thomas Hood's memory poured in and on 18 July 1854 the memorial was unveiled at Kensal Green Cemetery. The monument, topped with a bust of Hood, was sculpted by Matthew Noble (1817-1876) and contained two bronze reliefs illustrating his poems The Bridge of Sighs and The Dream of Eugene Aram. The inscription beneath the bust read "HE SANG THE SONG OF THE SHIRT".

Rising Success

The increase in Punch sales and popularity following the publication of the Song of the Shirt was quite remarkable and a huge step forward as far as Bradbury and Evans were concerned. Another success with the readership that year had been The Story of a Feather written by Douglas Jerrold and serialised in Punch over the course of 1843. In part of a note written in August 1843 by Charles Dickens to Bradbury and Evans concerning the printing of Martin Chuzzlewit Dickens remarked that "Punch is better than ever".

However the proprietors were still feeling some unease over the future prospects of the periodical. A sense of this strain can be felt in a line from a letter Bradbury wrote to his friend Joseph Paxton some eight months after the publication of the Song of the Shirt in August 1844.

"Mr Punch goes on increasing in sale and reputation - but it is a great task and anxiety." [39]

The real triumph as far as long-term Punch sales were concerned came with the publication in 1845 of Mrs Caudle's Curtain Lectures written by Douglas Jerrold and illustrated by John Leech. On 4 January 1845 readers were introduced to Job and Margaret Caudle:

"POOR MR. JOB CAUDLE was one of the few men whom Nature, in her casual bounty to women, sends into the world as patient listeners. He was, perhaps, in more respects than one, all ears. And these ears, MRS. CAUDLE - his lawful, wedded wife, as she would ever and anon press upon him, for she was not a woman to wear chains without shaking them - took whole and sole possession of."

Every night in bed as her husband tried to sleep Mrs Caudle would lecture her captive audience on his minor transgressions for that day, each one she believed would ultimately result in their ostracisation from society. The extraordinary popularity of the series was felt to be due to the fact that every reader could recognise a Mrs Caudle amongst their acquaintances. Written and published in thirty-six parts in 1845 the lectures were a phenomenal success; they were translated in to many different languages, performed on the stage, and before placing their weekly order news sellers would ask whether the forthcoming Punch issue contained any of the lectures in order to decide how large their order was to be. Jerrold himself was somewhat less than impressed at the public appetite for the Caudles. Speaking to Ebenezer Landells one day in the Strand he said:

"I have before said, the public will always pay to be amused, but they will never pay to be instructed."

Although he felt that he had written much better pieces and would much rather have received the public acclaim for his more serious works than for Mrs Caudle Douglas Jerrold was nonetheless as delighted as Bradbury and Evans were with the performance of the lectures. He apparently went

"radiant, to the weekly Punch dinners; and was merry there in the midst of the men he had met, for years, over that kindly, social board." [40]

It would seem that this fondness, esteem and camaraderie which the Punch staff and Bradbury and Evans had, on the whole, for each other, played a key role in the long-term success of the magazine. There were naturally differences of character, upbringing and opinion that would cause friction; Thackeray and Jerrold in particular disagreed politically with each other, with Jerrold and Mark Lemon being of a much more radical persuasion than Thackeray. Writing to author Charles Mackay (1814-1889), Jerrold said of his relationship with Thackeray:

"Thackeray and I are very good friends, but our friend T. is a man so full of crotchets, that, as a favour, I would hardly ask him to pass me the salt." [41]

And "He is the most uncertain person I know. To-day he is all sunshine - to-morrow he is all frost and snow."

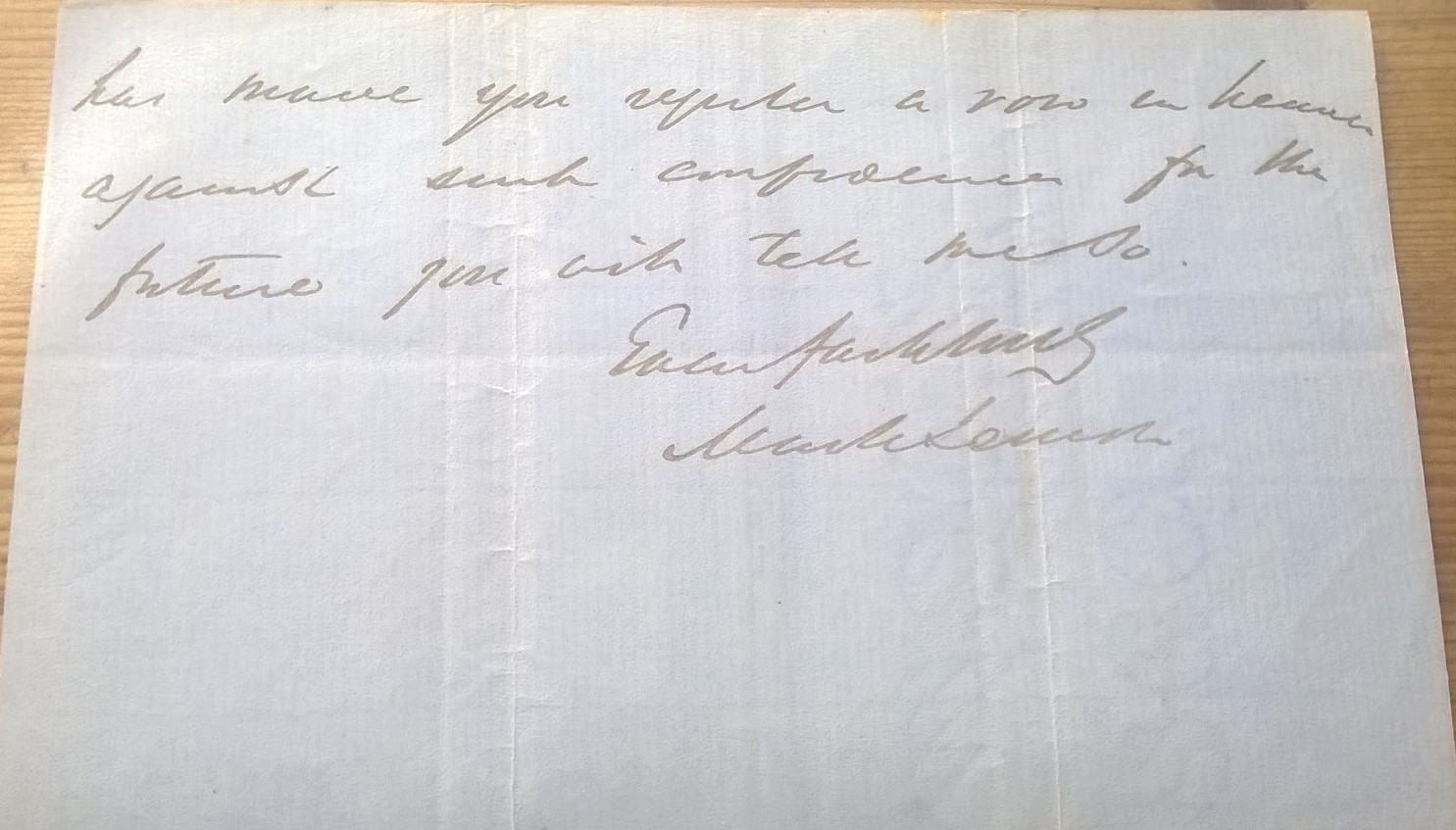

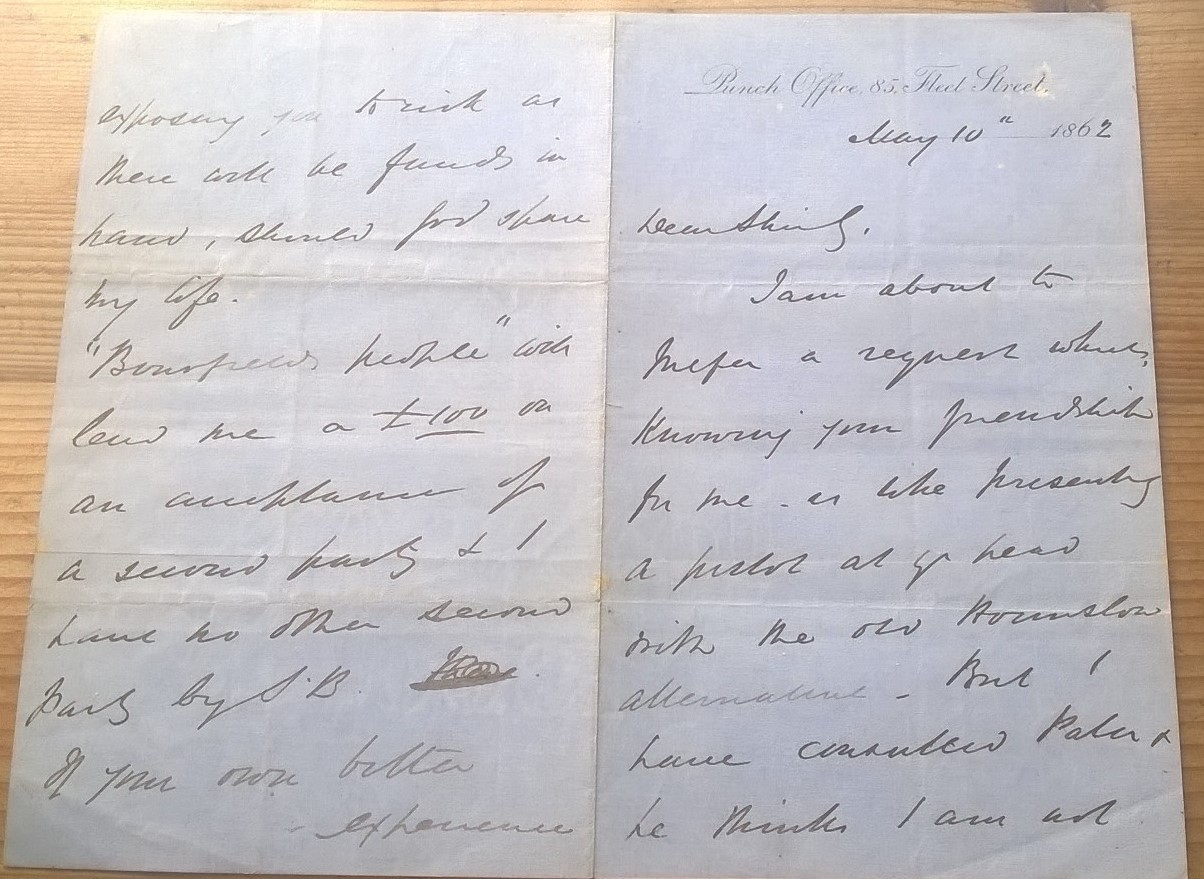

Click to enlarge. Letter on Punch Office headed paper from Mark Lemon to Shirley Brooks speaking about a loan for £100, with mention made of Frederick (Pater) Mullett Evans.

However there was an undoubted closeness and sense of brotherhood amongst the Punch staff and with Bradbury and Evans that extended beyond usual working practices. Mark Lemon in particular was treated as a dear friend and an equal rather than an employee; apparently Lemon would link arms with Bradbury and Evans in the street and stride merrily along to lunch with them at a nearby tavern. [42] The staff would often meet for excursions and dinners out. Thackeray recorded in a diary entry for Friday 10 March 1848 that a party had met at the office at Bouverie Street and had gone into the City to dine on beef steaks and sample port wine, followed by a visit to Tom's Coffee House, Cowper's Court, Cornhill, which he was less than impressed with, for drink and cigars. They then went on to Drury Lane Theatre where the Cirque National de Paris were performing, and the evening was rounded off by supper at 11.00pm at Charles Henry Offley's Tavern at 23 Henrietta Street, Covent Garden as they had dined early and were hungry! [43]

As part of their more business-like approach to the proprietorship of the magazine Bradbury and Evans paid the Punch staff a regular weekly salary; Thackeray wrote to his family in December 1843 that his pay from Punch was "more than double of that I get anywhere else". [44] Writing to his mother in June 1861 George du Maurier said

"I am doing initial letters for Punch which just suffices to keep me. I am trying to make a dead set at that paper, so as to be one of the regular staff someday. Leech is beastly idle, so Mark Lemon tells me, and gets his 1000£ a year salary. Tenniel gets 500£ a year for doing the large political block." [45]

Their business capital was also used on a more unusual basis to loan the staff money. Lemon in particular, with his large family, appears to have been in quite a precarious financial position over many years, and repeatedly applied to Bradbury and Evans and other friends for loans. The letter pictured on this page was written by Mark Lemon on 10 May 1862 to his friend and deputy Punch editor Shirley Brooks, and speaks about a loan for one-hundred pounds that Lemon was trying to secure. He had discussed this loan with 'Pater' (Frederick Mullett Evans) and was wondering if Brooks would be willing to act as a "second party" on the loan. Evans had apparently reassured Lemon that Brooks would not be exposed to any risk if he was willing to act in that capacity as "there will be funds in hand" should they be needed. Lemon concluded the letter by saying to Brooks:

"If your own bitter experience has made you register a vow in heaven against such confidences for the future you will tell me so."

Shirley Brooks himself sought financial help from Bradbury and Evans several times; one such request in November 1856 was met, as usual, with help, and he replied:

"MY DEAR B. & E., One word more of sincerest thanks for your kindness, which has much relieved my mind." [46]

John Leech, also a good friend of Bradbury and Evans, took many financial loans from them; in 1866, two years after his death Leech's estate owed Bradbury and Evans some two-thousand pounds. [47]

By 1845 Punch was reaching a weekly audience of approximately two-hundred thousand people. [48] This steady rise in the popularity of Punch with the reading public from the mid 1840s had a huge impact on the growth and success of Bradbury and Evans. In 1842, the year that they purchased Punch, the firm had six printing presses operating from their Lombard Street premises; by 1851 they were employing between three-hundred to four-hundred people and were the publishers for Charles Dickens and William Makepeace Thackeray, and a decade later were employing between four-hundred and five-hundred people. [49]

This section is to be continued.

References

- ^ Douglas Jerrold and Punch Walter Jerrold

- ^ The History of "Punch" M. H. Spielmann page 33

- ^ 1851 England Census Class: HO107; Piece: 1512; Folio: 18; Page: 28; GSU roll: 87846

- ^ 1841 England Census Class: HO107; Piece: 731; Book: 5; Civil Parish: St Clement Danes; County: Middlesex; Enumeration District: 8a; Folio: 30; Page: 3; Line: 1; GSU roll: 438833

- ^ Mark Lemon First Editor of Punch (1966) Arthur A Adrian page 33

- ^ Arthur A Adrian, Patrick Leary, M H Spielmann

- ^^ Oxford DNB R. M. Healey, ‘Lemon, Mark (1809–1870)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004

- ^ Bells New Weekly Messenger 12 December 1841

- ^ Perry's Bankrupt Gazette 7 August 1841

- ^ Cartoon Portraits and Biographical Sketches of Men of the Day/Shirley Brooks 1873 Tinsley Brothers

- ^ Worcester Herald 6 March 1830

- ^ 1841 England Census Class: HO107; Piece: 685; Book: 20; Civil Parish: St Pancras; County: Middlesex; Enumeration District: 20a; Folio: 9; Page: 13; Line: 18; GSU roll: 438801

- ^ 1851 England Census Class: HO107; Piece: 1517; Folio: 408; Page: 39; GSU roll: 87851 Registration district Clerkenwell. I am extremely grateful to a reader of this website for information on Richard Bryant post debtors prison.

- ^ GRO Reference: 1858 SAINT PANCRAS Volume 01B Page 74

- ^^^^ The History of Punch M H Spielmann

- ^ see Old Bailey Online: WILLIAM ANDREWS, CHARLES CARTER, Theft stealing from master, Theft receiving, 4th April 1842

- ^ The Punch Brotherhood. Table Talk and Print Culture in Mid-Victorian London (2010) Patrick Leary page 143

- ^ Memories of my Time, including personal reminiscences of eminent men (1870) George Hodder page 49

- ^ Bell's New Weekly Messenger 26 December 1841

- ^ A jorum of Punch with those who helped to brew it : being the early history of "The London Charivari (1895) Athol Mayhew

- ^ Punch volume 2 page 13

- ^ see essay by Sondra Miley Cooney William Somerville Orr, London Publisher and Printer: The Skeleton in W and R Chambers's Closet in Worlds of Print Edited by John Hinks and Catherine Armstrong page 139

- ^ Charles Dickens and his Publishers (1978) Robert L Patten page 110

- ^ The Letters and Private Papers of W.M.Thackeray Ed. Gordon N Ray vol ii page 54

- ^ John Leech and the Victorian Scene (1984) Simon Houfe page 49

- ^ The History of "Punch" M. H. Spielmann

- ^ John Leech and the Victorian Scene (1984) Simon Houfe page 25

- ^ Mark Lemon First Editor of Punch (1966) Arthur A Adrian page 61

- ^ see essay by Sondra Miley Cooney William Somerville Orr, London Publisher and Printer: The Skeleton in W and R Chambers's Closet in Worlds of Print Edited by John Hinks and Catherine Armstrong page 136

- ^ see essay by Sondra Miley Cooney William Somerville Orr, London Publisher and Printer: The Skeleton in W and R Chambers's Closet in Worlds of Print Edited by John Hinks and Catherine Armstrong page 140

- ^ Times newspaper 15 March 1900

- ^ From The Times newspaper report of 27 October 1843, we can glean that Mrs Bidell was a widow with two children, one of whom was a baby, she had been pregnant at the time of her husband's death, and her husband had died in an accident in January 1843

- ^ 1841 England Census Class: HO107; Piece: 716; Book: 13; Civil Parish: St Mary Whitechapel; County: Middlesex; Enumeration District: 10; Folio: 51; Page: 15; Line: 4; GSU roll: 438823

- ^ see various newspaper reports e.g. Morning Advertiser 11 January 1843 and Lloyd's Weekly Newspaper 15 January 1843

- ^ London Metropolitan Archives, Whitechapel St Mary, Register of Baptism, P93/MRY1, Item 019

- ^ The Morning Chronicle : Labour and Poor, 1849-50; Henry Mayhew - Letter VI

- ^ 1871 England Census Class: RG10; Piece: 530; Folio: 20; Page: 33; GSU roll: 823387

- ^ Lloyd's Weekly Newspaper London, England 14 December 1879

- ^ The Punch Brotherhood. Table Talk and Print Culture in Mid-Victorian London (2010) Patrick Leary page 145

- ^ The Life and Remains of Douglas Jerrold Blanchard Jerrold page 236

- ^ Forty Years' Recollections of Life, Literature and Public Affairs Mackay page 286

- ^ Mark Lemon First Editor of Punch (1966) Arthur A Adrian page 36

- ^ The Letters and Private Papers of W.M.Thackeray Ed. Gordon N Ray vol ii page 358-60)

- ^ The Letters and Private Papers of W.M.Thackeray Ed. Gordon N Ray vol ii page 135

- ^ The Young George du Maurier Ed. Daphne du Maurier page 50

- ^ Shirley Brooks of Punch (1907) George Somes Layard page 147

- ^ The Punch Brotherhood. Table Talk and Print Culture in Mid-Victorian London (2010) Patrick Leary footnote page 155

- ^ Punch: The Lively Youth of a British Institution (1997) Richard D Altick page 38

- ^ 1851 and 1861 England Census for Frederick Mullett Evans