Printers for Chapman and Hall

Chapman and Hall

The publishing house of Chapman and Hall, best remembered as Charles Dickens' publishers, was established towards the end of 1829 by William Hall (1800-1847) and Edward Chapman (1804-1880), coincidentally the same period during which Bradbury and Evans were establishing their printing partnership. The first advertisements for Chapman and Hall's publications in late 1829 carry the address of 3 Arundel Street, Strand, London. [1] This was a street built in 1678 on part of the site of Arundel House, running off the Strand practically opposite the church of St Clement. Number three Arundel Street was directly opposite the Crown and Anchor Tavern, where Dr Samuel Johnson and his friend James Boswell used to drink regularly. This property appears to have been a Chapman family home, it was also occupied by Edward Chapman's elder brother Thomas (1800-1895), a Land Agent and Surveyor who became a friend of Charles Dickens, and their three sisters Elizabeth, Ellen and Louisa. Elizabeth, known as Eliza, died at the house on 15 February 1844. Chapman and Hall only published from this building for a matter of a few months before moving around the corner to a building actually on the Strand itself, at number 186, three buildings away from the Arundel Street premises.

William Hall, born 19th October 1800, was the second of five children born to his parents John Hall, a Haberdasher, and Elizabeth (nee Magrath). The family lived above the haberdashery shop at 49 Cheapside, London, a street almost adjacent to St Paul's Cathedral; friends and neighbours described John Hall as "an honest and upright man". [2] Tragically when William had just turned ten years old his parents died within a month of each other; his mother died first in September 1810 and then horrifically the following month his father died as a result of having to have his leg amputated following an accidental fall. [3] John and Elizabeth left behind four surviving children, the youngest of whom, Emma, was just over one year old. [4] Not only did the young children have to cope with the loss of their parents but a little over a month after their father's death they lost their home and had to witness the entire contents of the haberdashery shop, which included luxury goods such as silks, linens, cashmere, lace shawls and silk handkerchiefs, ribbons, beads, feathers and flowers, being sold off at the request of his executors. Five days after that all the household furniture, goods and even John and Elizabeth Hall's clothing were also sold off. [5] Elizabeth Hall's extended Magrath family lived and worked in the surrounding area on Cheapside and Bread Street and so it is probable that the young children were taken in by one of them.

The Athenaeum Club in London in 1830. Engraved by James Tingle (1801-1858) from an original study (now in the Museum of London) by Thomas Hosmer Shepherd. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Despite their devastating loss and the huge upheaval in their lives, the young children all survived into adulthood and appear to have thrived. In 1833 William's younger brother Spencer Hall (1805-1875) was appointed Librarian of the famous Athenaeum Club situated at 107 Pall Mall; he held the position for the rest of his life. Elizabeth Hall's cousin Edward Magrath (1790-1861) was the Secretary of the Club, having succeeded his good friend the scientist Michael Faraday (1791-1867) to the role. The (at that time) male only club was established for gentlemen distinguished in Science, Literature, or the Arts; Charles Dickens was elected as a member in June 1838, and William Makepeace Thackeray was also a member.

Edward Chapman, born 13 January 1804 in the town of Richmond, Surrey, was the third of nine children born to his parents Thomas Chapman, a Solicitor and Sophia (nee Barrett). Edward Chapman had a comfortable middle class childhood, quite different from his friend and business partner William Hall, with both his parents surviving into relative old age. His older brother William, who like his father became a Solicitor, was educated privately at schools in Richmond and Isleworth, Surrey, and it is likely that Edward was similarly educated. The siblings all went on to have successful careers; two of his brothers, Thomas and George became Land Agents and Surveyors in London, his brother Frederick became a Medical Doctor in Richmond, and his brother Henry a Civil Engineer.

Chapman and Hall began their publishing careers on 1 January 1830 by co-publishing in parts priced at one shilling A New Topographical Dictionary of Great Britain and Ireland compiled by the writer John Gorton (c1771-1834). The first part contained forty-eight quarto maps engraved on steel by the map maker and engraver Sidney Hall (c1788-1831), and was very well received. A review in the Sunday Times in February 1830 stated "....we are highly pleased with the plan and execution. The accompanying maps are correctly engraved by Mr. Sidney Hall." Sadly despite the popularity of the Topographical Dictionary, life became extremely difficult for John Gorton, culminating in his suicide on 7 December 1834 by hanging at his home in Charlotte Street, Fitzrovia, central London. He had apparently had financial difficulties for some time before his death. [6]

Another serial co-publishing venture undertaken by Chapman and Hall in June 1830 was a publication called Chat of the Week. Written by James Henry Leigh Hunt (1784-1859), this was a short lived endeavour priced at six pence which contained "the most piquant or otherwise interesting passages on ALL subjects from ALL the periodicals, with original Matter and occasional Notes throughout." [7]

Chapman and Hall also published Landscape Illustrations of the Prose and Poetical Works of Sir Walter Scott. Issued between 1832 and 1833 with buff coloured wrappers in twenty-four fortnightly parts and priced at two shillings and six pence, the printers interestingly were Manning and Co, formerly in partnership with William Bradbury and William Dent. None of their earlier publications were printed by Bradbury and Evans.

As explored in more depth in the section focusing on Bradbury and Dent the country was deeply mired in an economic crisis during the period that both Chapman and Hall and Bradbury and Evans were trying to establish themselves. Chapman and Hall appear to have weathered the financial storm by proceeding cautiously and slowly, focusing somewhat more on book selling rather than publishing and by not taking huge speculative risks.

Printers of the Novels of Dickens

"...they are not only the best and most powerful printers in London, but have in all our transactions won my affectionate esteem and regard." ~ Charles DickensIn December 1835, The Squib, a new satirical annual of "poetry, politics and personalities" was published in time for Christmas. Priced at five shillings, published by Chapman and Hall and printed by Bradbury and Evans, it contained twelve drawings by the popular illustrator and caricaturist Robert Seymour (1798-1836), described in Bell's New Messenger as "the Prince of Caricaturists". Seymour had an idea which he presented to Chapman and Hall for a subsequent publication based around a club he called the Nimrod Club. Seymour's idea was that this would comprise of a series of comic illustrations based on the humorous mishaps of a group of Cockney sportsmen, with accompanying text linking the designs. Chapman and Hall liked Seymour's proposal and it was agreed that the illustrations would be published in monthly parts, with each part containing four plates. A writer was then needed to compose the text to accompany the illustrations, and after unsuccessfully approaching several other authors, on 10 February 1836 William Hall went to talk to a young reporter and writer at his lodgings in Furnival's Inn. Charles Dickens (1812-1870) writing under the pseudonym 'Boz', had had some successes with various sketches that he had written for the Morning Chronicle and Evening Chronicle and also for Bell's Life in London, but he was at that time largely unknown to the general population. Needing the money Dickens accepted Hall's offer to write the text to accompany Seymour's illustrations. Something appears to have been lost in translation somewhat by Dickens, however, as he wrote to his future wife Catherine Hogarth that night to say that "They (Chapman & Hall) have made me an offer of £14 a month to write and edit a new publication they contemplate, entirely by myself; to be published monthly and each number to contain four wood cuts." [8] Seymour would have expected to have taken the lead role in the publication. Bradbury and Evans were selected as the printers for this new venture. Their Lombard Street premises had a huge steam-driven cylinder press and a stereotype foundry, and since the founding of their partnership in 1830 they had acquired an excellent reputation for speed and efficiency with leading publishers in both book and serial printing. Dickens and Seymour set to work, Dickens informing Chapman and Hall on 18 February that the first chapter of the new publication, now referred to as Pickwick, would be ready the following day.

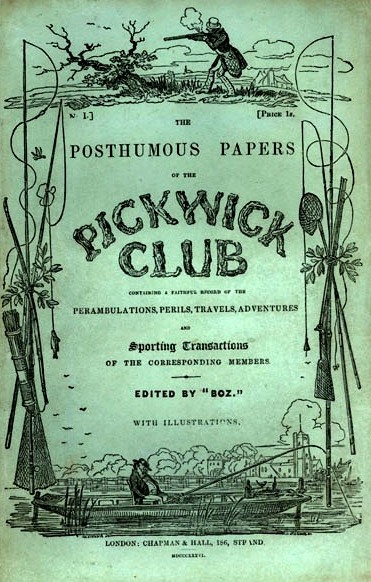

In March 1836 advertisements appeared in newspapers and journals for the first part of the new serial as, under Chapman and Hall's direction, Bradbury and Evans turned Dickens hand-written manuscript into an initial run of one thousand copies. On 31 March 1836, in distinctive green wrappers decorated with Seymour's artwork and priced at one shilling, the first part of The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club Containing a Faithful Record of the Perambulations, Perils, Travels, Adventures, and Sporting Transactions of the Corresponding Members. Edited by 'BOZ' was published.

Cover of Charles Dickens The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, published by Chapman and Hall, printed by Bradbury and Evans. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

Cover of Charles Dickens Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby, published by Chapman and Hall, printed by Bradbury and Evans. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

"Best and dearest of wives - for best of wives you have been to me - blame I charge you not anyone, it is my own weakness and infirmity, I don't think anyone has been a malicious enemy to me;" [11]

There was now a huge decision to be made as to the future direction of Pickwick. After discussion it was agreed between Chapman and Hall and Dickens that the number of illustrations should be reduced from four to two per issue and the text increased from twelve-thousand to sixteen-thousand words per month. For Issue three, illustrated by Robert William Buss (1804-1875), Bradbury and Evans were tasked to print one thousand copies. From issue four onwards Hablot Knight Browne ('Phiz') (1815-1882) took on the role of illustrator. Sales remained slow at first, gradually increasing as month by month the public became thoroughly entranced with Dickens' tale. In February 1837 Bradbury and Evans were printing fourteen-thousand copies of the Pickwick Papers, reaching a peak of forty-thousand copies at the serials end. [12]

In order to produce this huge volume of work, Bradbury and Evans had to make full use of their stereotype foundry. This use of stereotype plates enabled them to rapidly reproduce pages of type and was a technique that Bradbury and Evans fully embraced; in May 1858 they had just over 233,400 stereotype plates in stock. [13] In order to manufacture the plates workers would need to make a mould from each page of movable type by covering the surface, held fast in a frame, with plaster of Paris. Once the plaster had dried, it was carefully removed from the frame and the type face, trimmed and neatened and then baked in an oven until all moisture was removed, a process which would take about two hours. The heat of the oven would cause a contraction of the plaster with the result that a page printed from a stereotype plate would be a few millimetres smaller than a page printed from movable type. Next the hardened mould would be placed face down on a movable cast iron plate inside a box known as a casting box, and then the box cover, which had holes at each of its corners, was held in place with a screw thus holding the mould secure. The casting box was plunged into molten metal for several minutes whilst the metal ran into the mould through the holes in the box. Then, following total immersion and cooling in water, the contents of the casting box were removed. The plaster of Paris mould would be destroyed leaving behind a newly formed metal plate. The plate would then be thoroughly checked, removing any surplus lumps of metal if found from the inside of letters, and the back of the plates would be made uniform and even before the plates were mounted ready for use.

Example of a composing stick with letters placed upside down, left to right. By Wilhei (Own work) Creative Commons License 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

The process of turning Dickens' hand written manuscript into the printed word would have involved multiple skilled workers at Bradbury and Evans. The business occupied numbers 1-6 Lombard Street, giving them a vast space to work from. Compositors and Readers occupied the first floor, with presses and machinery on the ground floor, in 1842 there were six presses in total, with each machine requiring one man and two boys to work it, growing to twenty presses at the height of their success. [14] The usual working hours at the firm were 8.00am until 8.00pm, Monday to Saturday, although frequently employees were at work until 10.00pm, with all-night working not uncommon. Workers were allowed to take fifteen minutes for their lunch, an hour for dinner, and thirty minutes for tea. Deducting hours for meal times this would still mean that employees would be working in excess of sixty hours per week. Some of these workers were children; out of a staff of between three-hundred and four-hundred people in the 1850s there were fifty boys employed in the machine department alone and approximately one-hundred and fifty in the whole establishment, a figure which halved in the 1860s to a total of seven boys under the age of thirteen, and ninety-three between the ages of thirteen and eighteen. In the 1860s no women were employed under the age of eighteen. [15]

The manuscript would most probably have been divided out among several different Compositors in the Composing Room for typesetting. In sharp contrast to the cacophonous Machine Rooms, the Composing Room would be a quiet, orderly area with each Compositor concentrating intently on the work at hand. Standing for hour after hour each day Compositors were particularly liable to suffer from varicose veins and leg ulcers, and also to eye problems such as short sightedness from concentrating and focusing on small type for prolonged periods of time. One former Compositor who worked at Bradbury and Evans for over fifty years, Charles Cawte (1832-1907), reminisced about working from Dickens' copy: "Well I remember the thick, spluttering, blue ink, quill-penned manuscript. After getting over the first few lines the copy would not have been called 'bad'- that is, from a compositor's point of view." Often working from ink splattered pages these Compositors, who needed excellent manual dexterity skills, would pick up each individual metal letter from one of two cases, designated upper and lower, which rested on a sloping frame for ease of use. Capital letters and numbers were stored in the upper case which had ninety-eight boxes, small letters and spaces in the lower case which had between fifty-three and fifty-six boxes. The Compositors would have a frame to themselves and these frames would tend to be placed with one side against a window so that during the day the Compositors were able to take advantage of the natural light. They would then place the type upside down, working from left to right, into a composing stick. Reading from the section of the manuscript that they were responsible for, they would memorise several words at a time, spelling each one out in their heads as they went along, letter by letter. An experienced Compositor would be able to set up about two-thousand letters each hour. Lines of typeface would need to be spaced and justified into an attractive layout using blank spacing bars, and spelling and punctuation skills were essential as each Compositor had to pay for any mistakes made.

If time allowed, a galley proof would be run off on a cheaper paper and checked for mistakes in the Reading Room by Readers or 'Correctors of the Press' as they were sometimes known. Readers at Bradbury and Evans, such as Henry Vernon (b.a. 1814), were allowed to take an extra thirty minutes for their dinner if they so desired. The Readers would usually read the proof, looking for errors in the type, whilst a young boy would read aloud to them from the original copy. The galley proof was named after the tray, or galley, in which the type was placed; the proof would be on a long strip of paper with wide margins. Dickens would see, correct and revise the proofs also, he liaised frequently with Charles Hicks, the Foreman/Superintendent over these, requesting Hicks to send a boy to collect a proof from him, for instance, and speaking about receiving another proof from Hicks the following morning. These young Warehouse Boys would be used for all manner of menial jobs such as sweeping up, making up the fires, taking and receiving messages and running errands. Once the Readers and author were satisfied with the revisions and corrections to the galley proofs, these would be taken back to the Compositors who would make the necessary alterations, before making the type up into pages. The type would be carefully slid from the galley on to a large flat stone surface before a chase, or frame, was placed around it. The type was then locked into position using blocks known as quoins. Page proofs would then be printed off and a final proof would be read by the Readers and the author.

Part of Lombard Street, now Lombard Lane, off Fleet Street, London photographed in October 2015. This small street was dominated by Bradbury and Evans' printing establishment. Author's own photograph

The White Swan Public House on Fetter Lane, London, where Bradbury and Evans' employee George Gifford Beard was the Landlord. Photograph taken October 2015

The next stage was the final print. In addition to their much smaller presses, Bradbury and Evans had erected a printing machine based on a design by Augustus Applegath assisted by Thomas Middleton, an engineer from Southwark. This enormous, noisy, steam driven machine, stood approximately thirteen feet high and fourteen feet in length, and was capable of producing four-thousand two-hundred impressions an hour. This single machine had the capacity of four presses, with four places in which the Pressmen would insert paper, four cylinders to carry out the printing, and four points at which the printed sheets were delivered to the waiting men. The Superintendent in the Machine Room in the 1840s was George Gifford Beard, who interestingly was also the Landlord of the White Swan public house on Fetter Lane, London, a public house which was much frequented by printers. He was kept so busy with his work at Bradbury and Evans that his wife Mary was left to manage the pub for him! Once printed the damp sheets would be carried through to the Warehouse for processing. Warehousemen and Under Warehousemen such as Michael Fitzhenry and Robert Rowen would take the wet papers through to the heated Drying Room, and arrange the papers to dry over lines arranged around the room. Pipes in the room would be heated by steam and the pages left to dry for around twelve hours in this well-ventilated but warm environment. Once dry the work would be pressed by placing each individual sheet between glazeboards and inserting in a hydraulic press. After 'booking' or collation, done by gathering up from a table the separate pages of the work, starting with the last page and working towards the first, the work would be passed on to Book Binders, where it would be stitched and bound into the finished work. It is probable that Bradbury and Evans, at least during their early years, did not have their own Bindery. In the early 1840s copies of Chambers' Edinburgh Journal that they were printing for the publisher William Somerville Orr were sent for folding to William Thomas Bone and his father, also called William, who were working as Book Binders from 3 Broadway on Ludgate Hill, London. [14] The firm of Messrs Bone and Son moved to premises at 76 Fleet Street, the premises at which William Bradbury had had his first London printing office in 1824. [16] Bone and Son became one of the larger firms of London Book Binders, at their height employing more than eighty people; in the 1850s Chapman and Hall were using Bone and Son as their Book Binders. Bradbury and Evans were chosen by Chapman and Hall to print all of Dickens' early publications from Pickwick Papers in 1836 through to their break with him in 1844. In June 1844 Bradbury and Evans took over from Chapman and Hall as publishers for Charles Dickens, a working relationship that was to last for some fourteen years until 1858.

References

- ^ Bell's Life in London and Sporting Chronicle - London 27 December 1829

- ^ Morning Post 24 October 1810

- ^ Morning Advertiser 02 October 1810

- ^ London Metropolitan Archives, St Lawrence Jewry, Composite register: baptisms 1715 - 1787, marriages 1715 - 1754, burials 1715/16 - 1812, P69/LAW1/A/003/MS06976

- ^ Morning Advertiser - London 26 December 1810

- ^ County Chronicle, Surrey Herald and Weekly Advertiser for Kent 16 December 1834

- ^ Bells Life in London and Sporting Chronicle 30 May 1830

- ^ Dickens, Charles, Dickens: Letters (I-XII) Volume 1: 1820-1839 Pilgrim Edition, edited by Madeline House, Graham Storey, et al., Dickens letter to To MISS CATHERINE HOGARTH, 10 FEBRUARY 1836

- ^ Charles Dickens and his Original Illustrators (1980) Jane R Cohen page 43

- ^ Charles Dickens and his Publishers (1978) Robert L Patten page 65

- ^ Hertford Mercury and Reformer 26 April 1836

- ^ Charles Dickens and his Publishers (1978) Robert L Patten page 68

- ^ Printing: Its Dawn, Day and Destiny (1858) Henry Riley Bradbury

- ^^ see Old Bailey Online: WILLIAM ANDREWS, CHARLES CARTER, Theft stealing from master, Theft receiving, 4th April 1842

- ^ see Commission on the Employment of Children, Young Persons and Women in Agriculture Third Report of Commissioners 1870

- ^ Morning Advertiser 04 March 1847