William Dent

Family Overview

- Mother: Elizabeth Chapman (c.1764-1793)

- Father: John Dent (born 1767)

- Wife: Mary Bradbury (1803-1850)

- Children: Edward John Dent (1826-1893); William Henry Dent (born 1828); Orlando Philip Dent (1834-1850)

Family History

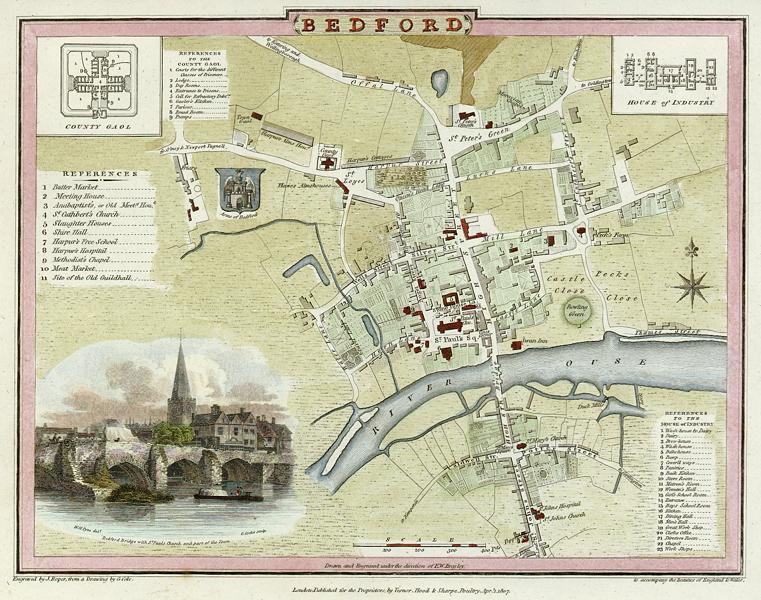

William Bradbury's first business partner and brother-in-law, William Dent, was born in the densely populated parish of St Clement Danes, London on Saturday 11 February 1792. He was the second and youngest son of John Dent (b 27 July 1767) and Elizabeth nee Chapman (1764-1793). [1] William's mother, and her extended family, were from the town of Bedford in Bedfordshire, where her father held the post of Mayor in 1772; William's father, and his extended family, were from London. His parents had married at the beautifully ornate parish church of St Paul's, Bedford on 1 October 1789, before moving to London where their first child Edward John was born on 19 August 1790.

The headstone of William's mother Elizabeth Dent (nee Chapman) in the churchyard of St Peter de Merton, Bedford. This headstone was erected in 1851 by William's brother Edward John and replaced the original headstone.

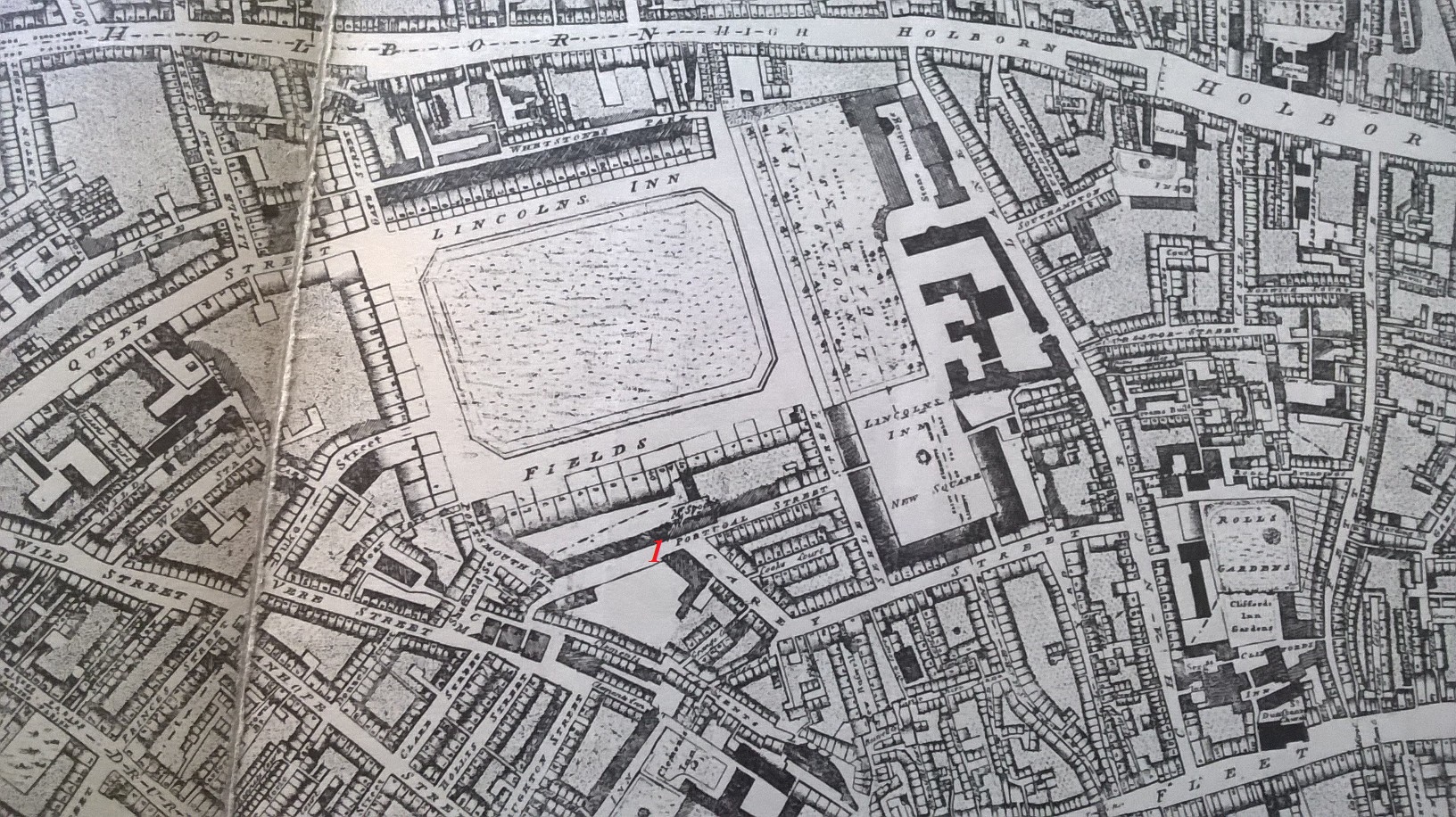

Click to enlarge. Detail from Richard Horwood's Map of London in 1799 showing Portugal Street, Lincoln's Inn Fields, marked with a red number 1. The Dent family lived on Portugal Street from 1768.

Portugal Street, Lincoln's Inn Fields, London, taken in December 2015. Nothing of the original street survives today.

John Dent son of John Wright Dent of the parish of St Clement Danes in the County of Middlesex pastry cook doth put himself apprentice to Maria Dent widow of Thomas Dent late Citizen and Clothworker of London deceased. [3]

Thomas Dent was his grandfather and Maria was Thomas' fifth wife, who, like Thomas previously, ran the King George III Coffee House at Lower Thames Street, London, adjacent to the Tower of London, which would have been frequented primarily by ship brokers, agents and merchants. [4] In order to carry out retail trade one had to be a Freeman of the City of London. This first of all meant becoming a Freeman of one of the Livery Companies of London and to this end Thomas Dent became a Freeman of the Guild of Clothworkers by paying the sum of forty-six shillings eight pence on 6 March 1765. [5] He was described at this time as a Coffee Man, and in September 1781 Maria was described as a Coffee Woman. Becoming a Freeman of a Livery Company did not mean necessarily working at that particular trade. In October 1788 when he was granted his Freedom John Dent was listed as a Coffee Man, living at 11 Portugal Street London.

Whilst undergoing his legal studies during the 1770s and early 1780s William Pitt the Younger (1759-1806), future Prime Minister, particularly enjoyed the convivial atmosphere of Serle's Coffee House which was situated close to the Dent's house, on Carey Street by New Square. It was described in 1804 [6] as having "Good soups, dinners and beds.". In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries Coffee Houses were hugely popular meeting places with people from all walks of society. The lack of alcohol made for a much calmer, less violent and more civilised atmosphere in comparison to what was often found in the local inns. For the entrance fee of just one penny the customers, who were predominantly male, would gather together with friends and acquaintances over coffee to read and hear the news, discuss politics and literature, gossip, debate and talk business. Later in the nineteenth century the popularity of the Coffee House waned somewhat, their place in society eventually being usurped by the rise of the Gentleman's Club.

Edward John and William Dent were born at 11 Portugal Street, a street which runs parallel with Lincoln's Inn Fields just off the Strand. The wider Dent family had lived on Portugal Street since at least 1768; it was the street that their paternal grandparents John Wright Dent (1738-1819) and Margaret nee Hull (d. 1775) lived on, and was where William's father John Dent grew up. In the 1780s the widowed John Wright Dent worked as a Pastry Cook on Portugal Street [7] before working as a Wax and Tallow Chandler from the early 1790s, making candles from animal fats and beeswax for use in homes and churches. In his London survey of 1720 the clergyman and historian John Strype (1643-1737) described what was to become Portugal Street as follows:

"On the Back side of Portugal Row, is a Street which runneth to Lincolns Inn Gate, which used to pass without a Name, but since the Place is encreased by the new Buildings in Little Lincolns Inn Fields, and the settling of the Play House it may have a Name given it, and not improperly, Playhouse Street."

Strype was referencing the fact that from the mid seventeenth century until the 1740s there was a theatre situated alongside Portugal Street. This theatre played host to John Gay's The Beggars Opera in January 1728 and performances by George Frederic Handel (1685-1759) between 1739 and 1741. In 1669 Nell Gwynn (1650-1687) the mistress of King Charles II had lodgings at a property by Lincoln's Inn Fields and acted in, and attended, performances at the theatre. During the Dent family's era the building was no longer used as a theatre but had several other uses, one such from 1794 to 1847 was as the pottery and china warehouse of the bone china manufacturer Josiah Spode, before finally being demolished in 1848.

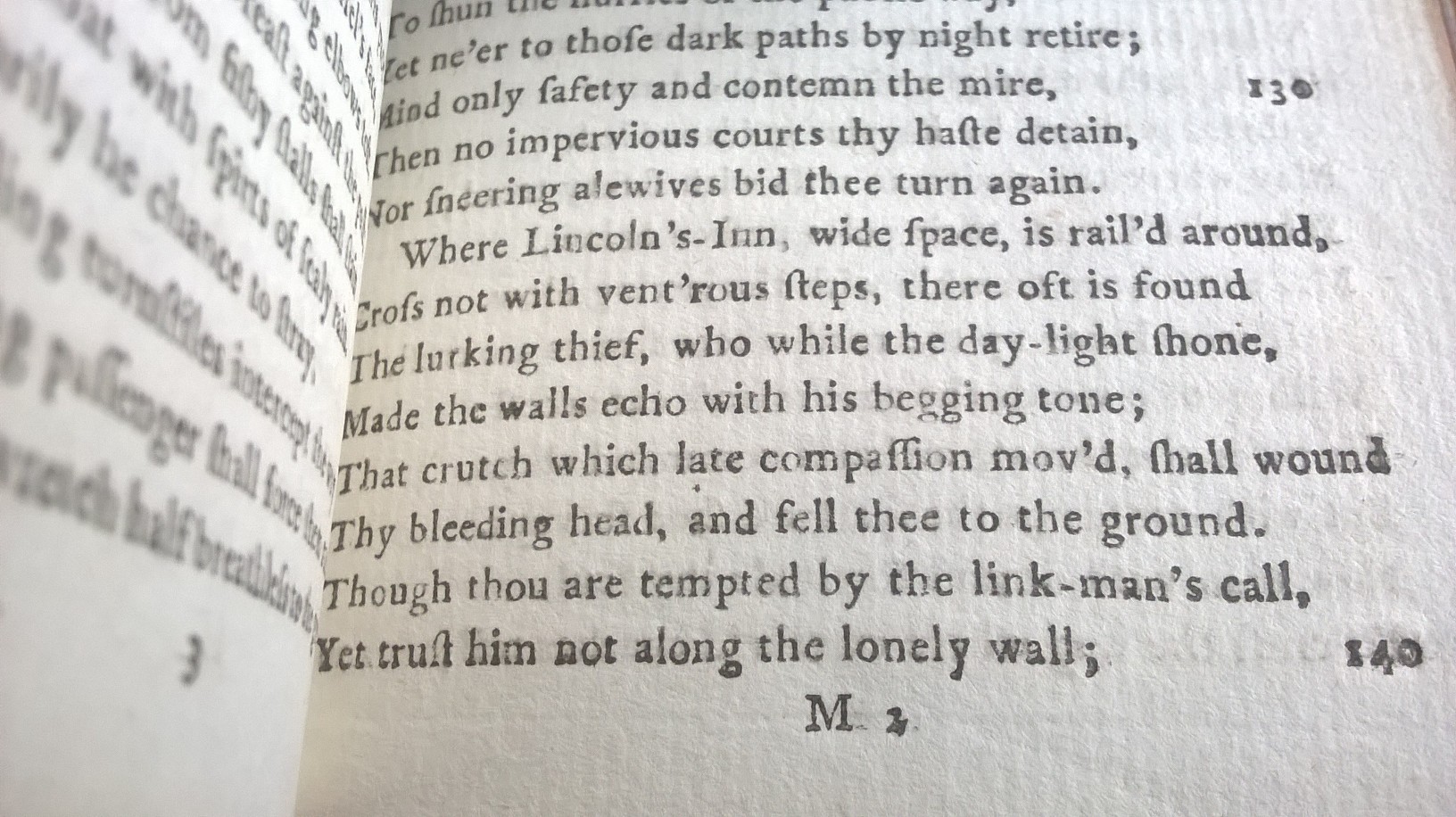

Lincoln's Inn Fields, thought to be named after Henry de Lacy, 3rd Earl of Lincoln, had been developed in the seventeenth century with large, extremely smart houses for the wealthy and local gentry. It sits alongside Lincoln's Inn, one of London's four Inns of Court but during this period the area had quite a mixed reputation. It was said to be "the largest and handsomest square, not only in London, but in Europe" but was also described as being home to beggars and vagrants in the day and thieves and robbers at night. Writing in 1716 John Gay (1685-1732) in his poem Trivia, or The Art of Walking the Streets of London spoke of the dangers of crossing Lincoln's Inn Fields at night:

"Where Lincoln's-Inn wide space is rail'd around, Cross not with vent'rous step; there oft is found The lurking thief, who, while the day-light shone, Made the walls echo with his begging tone. That crutch, which late compassion mov'd, shall wound Thy bleeding head, and fell thee to the ground. Though thou art tempted by the linkman's call, Yet trust him not along the lonely wall; In the midway he'll quench the flaming brand, And share the booty with the pilfering band."

Painting showing the pillory at Charing Cross, London c1808. Stocks and a whipping post were in place on Portugal Street, London until 1827. By Thomas Rowlandson (1756–1827) and Augustus Charles Pugin (1762–1832) (after) John Bluck (fl. 1791–1819), Joseph Constantine Stadler (fl. 1780–1812), Thomas Sutherland (1785–1838), J. Hill, and Harraden (aquatint engravers) Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The Times newspaper of Saturday 1 July 1786 spoke of a gang of pickpockets who "infested" the lanes around Lincoln's Inn Fields, who would draw out knives if they were detected. Until 1827 a pair of stocks and a whipping post, were in place practically outside the Dent's front door, at the intersection of Portugal Street with Carey Street. The use of this form of punishment meant that petty criminals would be subjected to public humiliation and deeply inhumane treatment; in November 1752 eight women accused of 'lewd acts' were tied in pairs to the whipping post on Portugal Street before being "severely whipped". We do not know just how sustained their ordeal was but sadly can imagine. The Portugal Street stocks gradually fell in to disrepair, however a newspaper report in March 1809 stated that the local Magistrates had ordered them to be repaired and that local rogues and vagabonds were to do penance in them.

On Friday 2 June 1780 Londoners became embroiled in a world of fear and tumult. William's then thirteen year old father and grandfather became reluctant eyewitnesses to the seven days of economic, political and anti-catholic rioting that occurred on their doorstep during what are now known as the 'Gordon Riots'. In the words of the poet William Cowper these riots left "a metropolis in flames and a nation in ruins". Lord George Gordon (1751-1793), head of the Protestant Association formed to protest against the Papists Act of 1778, called for people to gather on the Friday to march to parliament to present a petition to the House of Commons calling for the repeal of the Act.

Painting by John Seymour Lucas (1849-1923) depicting an incident during the Gordon Riots of June 1780. Source public domain via Wikimedia Commons.

"They waked us between 12 and 1, with noise and shouting; we got up to look, and saw a great crowd, but knew nothing of fire till this morning; as you know, the chapel is in Duke Street.....They have taken all the images and everything within the chappel that they could find, and pulled all to pieces and burnt before the door; broke the windows and burnt the frames and doors of the chappel."

Eventually soldiers arrived at the scene, thirteen of the rioters were arrested and the crowd was dispersed. That same night the Roman Catholic Chapel attached to the Bavarian Embassy in Warwick Street, Golden Square, Soho was attacked and destroyed in a similar manner, although no fire was started. A house in Little Queen's Street, Lincoln's Inn Fields belonging to a Mr Maberley, a Coach Painter, was broken into and destroyed, as was The Ship Alehouse in Duke Street, Lincoln's Inn Fields. Over the next few days outbreaks of rioting and violence spread across the City until by Wednesday 7th June London was in uproar. Bands of men carrying iron bars called at homes and demanded money from the householders. Widespread destruction in the City included the house of Justice Cox in Little Queen's Street, Lincoln's Inn Fields which was destroyed by fire alongside four houses in Great Queen's Street; at Fleet prison, King's Bench Prison, and Newgate Prison prisoners were released and the prisons torched; prisoners were set free from the Marshalsea Clink; an attack was attempted on the Bank of England; and the house and gin warehouse of Roman Catholic distiller Thomas Langdale near Fetter Lane were set on fire, culminating in a massive explosion and large loss of life. The flames could apparently be seen over thirty miles away. A printed hand-bill was distributed informing the public:

"Whereas a great Number of disorderly Persons have assembled themselves together in a riotous and tumultuous Manner, and have been guilty of many Acts of Treason and Rebellion, whereby it has become absolutely necessary to use the most effectual Methods to quiet such Disturbances, to preserve the Property of Individuals, and to restore the Peace of the Country: This public Notice is therefore given, to advise and exhort all peaceable Subjects to keep themselves quietly in their own Houses, lest they should suffer with the Guilty."

Thousands of soldiers were deployed to quell the rioters, newspaper reports at the time spoke of there being at least fifteen-thousand troops. Cowed by the military the rioters dispersed and the riots were effectively over by the evening of Thursday 8 June; however in total some two-hundred and eighty-five people had died, most at the hands of the soldiers, and twenty-five individuals were subsequently hanged for their part in the riots. We can only begin to imagine how the Dent family must have felt at this time. William's grandfather was forty-two years old and had been widowed five years previously. In June 1780 he had four children to care for, William's father, John, was the eldest aged thirteen, followed by Thomas aged nine, George aged eight and Margaret aged seven, the younger children in particular must have been so scared. Charles Dickens was later to write about the Gordon Riots in his novel of 1841 Barnaby Rudge: A Tale of the Riots of Eighty.

Early Life

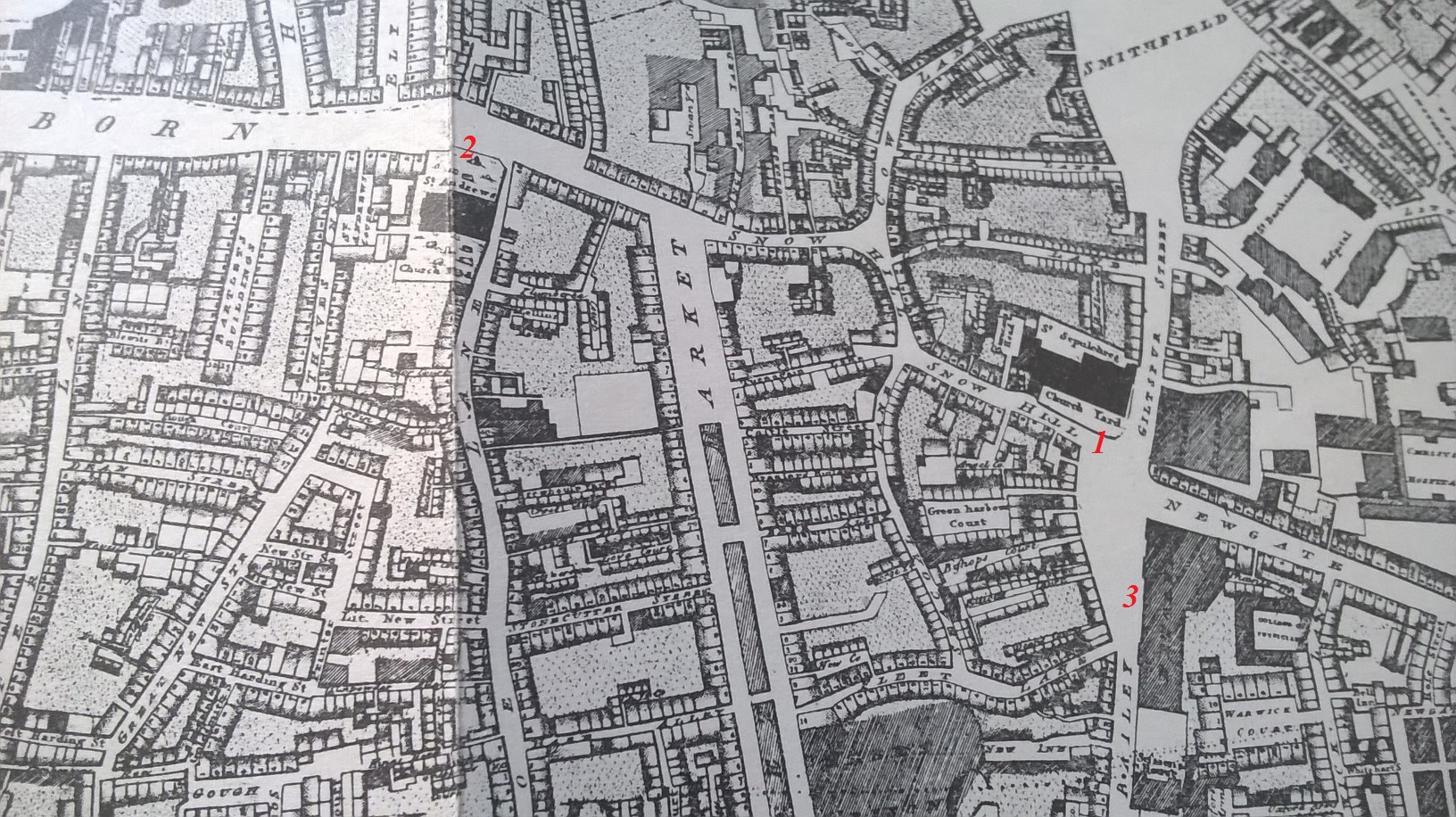

Click to enlarge picture. Detail from Richard Horwood's 1799 Map of London showing both St Sepulchre and St Andrew's churches numbered 1 and 2 respectively in red. Also numbered is Newgate Prison, numbered 3.

To briefly recap we know that William Dent was born in London on 11 February 1792 and that his mother had died before his second birthday, leaving his twenty-five year old father alone with the two young children.

Map showing the town of Bedford, Bedfordshire as it was in 1806, from an engraving by J Roper after a drawing by G Cole. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

At this time Bedford was a relatively small agricultural town but also part of a thriving lace making region. Indeed the county had been at the heart of England's lace making industry since around the middle of the sixteenth century, with farm labourers supplementing their meagre agricultural wages with money from the making of lace.

During William's ninth year in Bedford a major disaster struck the town. On Tuesday 25 May 1802 fire broke out in the parish of St Peter. It was thought to have been caused by a stray spark at the Blacksmith's forge landing upon the thatched roof. The roof quickly ignited, the fire took a hold and spread rapidly from property to property with dreadful consequences for the town's inhabitants. By the time the fire had been brought under control the area was absolutely devastated; in total some seventy-two houses had been completely destroyed, and around seven-hundred people had lost all that they owned. [9] We do not know if William's family were directly affected by the fire, but clearly the aftermath would have had a major impact upon the lives of all the townsfolk for quite some considerable time.

William's grandfather Edward Chapman died on 18 February 1806 at the age of seventy-six, a week after William's fourteenth birthday. [10] In his will Edward left William a property tenanted to a Mr Francis Norris, together with the associated buildings and land situated on Bedford's High Street. In addition he bequeathed him a silver watch that had belonged to his late son William, and bequeathed William's brother Edward John a silver watch that had belonged to his late son Thomas. Both boys were also to receive one-hundred pounds when they turned twenty-one. There was an additional bequest to William of one-hundred pounds which was to provide for his maintenance, education, clothing, apprenticing and 'bringing up' until he reached the age of twenty-one. [11] He had clearly cared deeply for William.

Following his grandfather's death William's uncle, who was also named Edward Chapman (1763-1811), assumed responsibility for the management of William's financial affairs. The Bedfordshire Archives Offices hold an accounts book which Edward Chapman kept on behalf of William Dent. [12] The records inside start in 1806 and offer us an interesting glimpse into William's life. They show for instance that his hats were bought from Mr Gilham at a cost of ten shillings six pence; shoes were purchased approximately twice a year from William Malden and stockings bought from Mr Charwell at four shillings nine pence per pair. In March 1808 a large clothes chest was bought from Mr Bright for one pound one shilling, and in August of the same year William received four pounds for a journey to London, presumably to visit his family there. Twice a year William received an income of six pounds ten shillings from Francis Norris as payment of rent on the property that he had been left by his grandfather.

At the end of December 1806, aged fourteen, William began to learn the art of printing when his uncle apprenticed him to Mr John Barnes, a printer with a shop on Bedford's High Street. Mr Barnes had established this shop on the High Street a year previously, and advertised himself as a printer, bookseller, stationer and binder. [13] Unfortunately by October 1808 John Barnes had suffered huge financial difficulties, culminating in his bankruptcy. He assigned his estate and effects to Charles Maxey, a lawyer in London, and to William Brown an auctioneer in Bedford, for the benefit of his creditors. [14] When his stock was auctioned off it contained, amongst many other things, upwards of two-thousand books, silver pencil cases, ebony and silver plated inkstands, portable writing desks, thirty-thousand pens and quills, a large quantity of black and red sealing wax, writing and printing papers and "every article required in the stationary (sic) line of business". [15] I have not yet managed to establish where William continued his apprenticeship following John Barnes' bankruptcy. It would appear that William was still living in Bedford in 1809 as the accounts show purchases during that year of sundries such as hats and shoes etc. It may be that he continued his apprenticeship in Bedford under the printer James Webb, who also ran a circulating library in Bedford consisting of three-thousand volumes of books. Edward Chapman's records of payments on William's behalf to hatters and shoemakers cease to be detailed in the accounts after December 1810. On 24 September 1810 William received five pounds for a journey to London and it may be that he took up an apprenticeship in London around this time. Records show a William Dent being apprenticed to James Ramshaw, a printer of 33 Fetter Lane, London, in August 1810, although there is nothing to show that this is 'our' William Dent. [16]

William and Edward John's widowed father John Dent married again, the day before William's third birthday. [17] Their new stepmother, Mary Wright, was also widowed, but I do not know if she brought any children of her own into the marriage. William's father and stepmother were living in the parish of St Sepulchre without Newgate, Holborn when they married, which is just over half a mile from William's birthplace of Portugal Street, and I believe they continued to do so for sometime afterwards. St Sepulchre's church stood opposite the notorious Newgate Prison which had had to be extensively repaired following fire damage sustained in the Gordon Riots of June 1780. Three years later the place of execution for prisoners sentenced to death moved to a public site outside Newgate Prison from the original location at Tyburn near to Marble Arch. Public hangings at Newgate took place almost monthly.

Dent clock at St Pancras International Station, London. Author: Christine Matthews [CC BY-SA 2.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Towards the end of the 1780s or early in the 1790s William's paternal grandfather John Wright Dent became a Tallow Chandler. On the 17 July 1792 he married for a second time, his new wife was Mary Jacques of the parish of St George, Hanover Square, London. According to the Westminster Rate Books in 1788 Mary Jacques was living on Chandler Street, Hanover Square, and from the time of their marriage until 1806 it would appear that number 19 Chandler Street, Hanover Square was being used as business premises for John Wright Dent, trading as J W Dent Wax and Tallow Chandler [18] On 20 August 1804 William's brother Edward John was apprenticed to their grandfather John Wright for seven years to learn the craft of the Tallow Chandler. As part of the apprenticeship agreement John Wright had to provide lodgings for Edward John, and this he did at the home of a cousin Richard Rippon, who was a Watchmaker living on King Street, Westminster. Spending time with Richard Rippon and watching him at work, Edward John became captivated by the art of watchmaking, and so in February 1807 his grandfather, with the agreement of Edward's father John, transferred his apprenticeship over to the Watchmaker Edward Gaudin so that he could learn to become a Watchmaker himself. [19] This was the start of a professional life that would see Edward John Dent lauded as Watch and Chronometer Maker to Queen Victoria and Prince Albert; the explorer David Livingstone (1813-1873) purchased and used a Dent chronometer during his explorations of Africa; and Dent was awarded, amongst many other commissions, the commission to make the clock for the Palace of Westminster clock tower known as 'Big Ben' on 25 February 1852. At the time of his death in March 1853 he had properties at 61 Strand, 34 Royal Exchange and 33 Cockspur Street and left personal property worth, at the time, seventy-thousand pounds. [20] The company that he founded is still in existence and in 2006 Dent and Co were commissioned to make the station platform clock at St Pancras International Station, London.

Photographic print of the trade card of William Dent's Great Uncle Thomas Dent and his business partner John Corbould. British Museum issued under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license.

A familial link to the printing industry exists through William and Edward John's great uncle Thomas Dent (born about 1740). He was apprenticed in 1755 to the Engraver John Corbould (1726-1775) of Foster Lane, London, situated to the north-east of St Paul's Cathedral. Corbould's son John (1755-1805) and grandsons John (b 1779) and Charles (1787-1825) were also Copperplate Printers and Engravers, working from 37 Fosters Lane, London. It would appear that Thomas went into partnership with John Corbould the first; in 1766 the Public Advertiser of Tuesday 5 August carried an advertisement for a series of prints by William Hogarth (1697-1764) with commentaries commissioned by his wife, the first of which, containing A Harlot's Progress, was available from "Corbould and Dent, Engravers, in Ball-Alley, Lombard-street". At some point before June 1774 Thomas went into partnership with a William Innes. One of their trade cards advertises "Dent & Innes Engravers & Printers. N W Ball Alley, Lombard Street, London." [21] This partnership was dissolved in June 1774 and Thomas appears then to have worked on his own from the Ball Alley premises as an Engraver and Printer until being declared bankrupt in 1777. I can find nothing after this date relating to Thomas' business activities until 3 June 1801 when Benjamin Vernon, a Copperplate Printer of 8 Little Eastcheap London, was granted the Freedom of the Clothworkers Guild following a seven year apprenticeship, and Thomas Dent was listed as his Master. Little Eastcheap was just a short distance from Ball Alley, Lombard Street.

The Middle Years 1822-1829

With so much unknown about William Dent's life, it is refreshing to assert that we do know for a fact that he was in the city of Lincoln, Lincolnshire by the end of 1822. An advertisement in the Stamford Mercury of 20 December 1822 advised readers that a ball was to be held at the City Assembly Rooms on Thursday 26 December, hosted by Mr Lings a dancing master. It sounded rather a grand affair:

"The great variety of elegant dances on this evening will consist of upwards of one hundred various steps, and three hundred different figures, independently of country dances, which Mr. L. flatters himself have never been displayed in Lincoln on such an occasion."

The dancing was to commence at 9.00pm and tickets, priced at seven shillings for a double ticket, or four shillings for a single, could be obtained directly from Mr Lings, or from "BRADBURY and DENT, Printers, Cornhill".

For a detailed look at William's time in partnership with William Bradbury please see the section on Bradbury and Dent.

What drew William Dent to Lincoln is a mystery. At some point he met and fell in love with Mary Bradbury (1803-1850), sister of William Bradbury, and following Bradbury and Dent's move to London in 1824, William and Mary were married at the church, known as the Journalists' Church, of St Bride, Fleet Street on Saturday 4 June 1825. Their brothers William Bradbury and Edward John Dent were witnesses to the marriage. William and Mary took a house in the parish of St James, Clerkenwell, just under a mile to the north of where William lived in his youth, and were joined as near neighbours by William Bradbury and his wife Sarah following their marriage a year later. On Saturday 4 March 1826 Mary gave birth to their first child, a son whom they named Edward John after William's elder brother. He was joined a little over two years later on Monday 26 May 1828 by a brother whom William and Mary named William Henry. Since their arrival in London from Lincoln William Dent and his partner William Bradbury had worked hard through difficult economic times to establish themselves as a trusted and respected firm of printers. They had had an early specialism in printing law books and had also worked for leading London publishers such as Charles Knight (1791-1873) and Hurst, Chance and Co of St Paul's Churchyard. However, sometime during 1828 or 1829 William Bradbury made the acquaintance of Frederick Mullett Evans, possibly whilst Bradbury and Dent were undertaking work for Hurst, Chance and Co where Frederick Mullett Evans was employed. Bradbury clearly identified something in partnering with Evans that appealed to him more than continuing in partnership with Dent. The two brothers-in-law ended their business relationship on 31 December 1829 and William Bradbury entered into a new partnership with Frederick Mullett Evans, establishing the printing and publishing house of Bradbury and Evans.

Post Bradbury and Dent

What then became of William Dent? On Saturday 14 April 1832 the social reformer and philanthropist Robert Owen (1771-1858) launched a weekly magazine titled "The Crisis: Or The Change From Error And Misery, To Truth And Happiness", priced at one penny. Part of its remit was to "discourage religious animosities, political rancour, and individual contention: its fixed purpose being to promote real charity, kindness, and union among all classes, sects and parties." The magazine was printed from Owen's premises on Burton Street and Gray's Inn Road and the printer was a William Dent of London, I strongly suspect that this was 'our' William Dent. The magazine was published between 1832 and 1834, and William Dent appears to have been the printer until 1833. William and Mary moved house from Clerkenwell to a property south of the River Thames at 3 Gray Terrace in Southwark, and six years after their son William Henry was born Mary gave birth to a third son on Thursday 7 August 1834. They named him Orlando Philip after two of Mary's brothers. Orlando was baptised the following June at the church of St John the Evangelist in Westminster, now a concert hall. The family were living at Gray Terrace, Southwark and William was working as a Printer. I can find no trace of the family then until six years later when the 1841 Census of England and Wales shows that William, Mary and Orlando had moved back to the parish of St James, Clerkenwell and were living in a house on Clarence Place. The houses there had been built in the 1780s and 1790s and were mostly three storey buildings with basements. The Dent's near neighbours had professions such as architect, clerk, independent means, plumber, stationer, optician, and so William and Mary were living in a fairly well-to-do area. Sadly the next time I trace the Dent family it is in desperately tragic circumstances. They had moved again and were living at 16 Lower Calthorpe Street, Gray's Inn Road. On Tuesday 10 September 1850 William and Mary's youngest son Orlando died from pulmonary tuberculosis at their home aged just sixteen years old. An announcement in The Times newspaper the following day read:

"On the 10th inst., of consumption, aged 16, Orlando Philip Dent, the beloved son of Mr. William Dent, of Calthorpe-street, and nephew of Mr. Edward J. Dent, 82, Strand."

He was buried at Highgate Cemetery four days after his death. Shockingly just a month after Orlando's death, on Friday 11 October 1850 William's wife Mary died. She died at home and William was with her; she was forty-seven years old and had been suffering from bronchitis for the past eighteen months. Her death was not announced in The Times newspaper, however an announcement in the London Evening Standard on 14 October 1850 simply read:

"On the 11th inst., Mary Dent, the wife of William Dent, formerly of Bedford."

She too was buried in Highgate Cemetery, one month and one day after her youngest son.

It is impossible to imagine the effect of this tragedy on William and his two surviving sons Edward John and William Henry. They moved from the house on Lower Calthorpe Street where Mary and Orlando had died and took a house at 17 Laurie Terrace, St George's Road, Southwark. William worked as a Proof Reader for a Printer; Edward John, like his namesake Uncle, was involved in watchmaking, working as a Lever Escapement Maker; and William Henry was a Clerk to a Merchant. Interestingly when William's brother Edward John Dent first drew up his will in 1849 he left the sum of one-thousand pounds to be divided equally between his three nephews Edward John, William Henry and Orlando Philip. However before his death in 1853 he amended this will, revoking the bequest to his nephews and instead left the one-thousand pounds originally intended for them to his wife Elizabeth. I wonder if some sort of dispute occurred between William Dent and his brother Edward John as at the time of his death Edward John left personal property worth seventy-thousand pounds, a small fortune at the time, and yet absolutely nothing was bequeathed to his brother or surviving nephews. Perhaps Edward John junior had worked for Edward John senior and something had occurred there that caused a falling-out; Edward John junior did not continue in the watchmaking profession becoming instead an Insurance Clerk.

Before his death in January 1858 William moved house again to a property at 9 Hemingford Terrace, East Barnsbury Road, Islington. [19] It is interesting to note that in the newspaper announcement of the death of his wife Mary in October 1850, William (or whoever submitted the announcement) stated that he was formerly of Bedford. When his own death was announced in the Hertford Mercury and Reformer on 30 January 1858, the announcement read:

"On the 24th inst., at Barnsbury, William Dent, Esq., formerly of St. Paul's Bedford, aged 66."

William Dent ultimately inherited quite substantial land and property from his late maternal grandfather's estate in Bedford; this legacy went on to benefit not only William but subsequent generations as well in terms of education and business investments. [8]

William died from heart disease on Sunday 24 January 1858, a few days short of his sixty-sixth birthday. He had lived long enough to meet his first grandchild, a daughter Louisa born to his son Edward John and daughter-in-law Hannah on 9 February 1857. William appointed his eldest son Edward John as the executor of his estate; his personal effects amounted to three-thousand pounds.

References

- ^ Baptism Register Parish of St Clement Danes, Westminster, London

- ^ National Burial Index for England & Wales

- ^ London Metropolitan Archive; Reference Number: COL/CHD/FR/02/1101-1108 London, England, Freedom of the City Admission Papers, 1681-1925

- ^ The National Archives; Kew, England; Prerogative Court of Canterbury and Related Probate Jurisdictions: Will Registers; Class: PROB 11; Piece: 999 Will of Thomas Dent: Probate date 4 July 1774.

- ^ London Metropolitan Archive; Reference Number: COL/CHD/FR/02/0917-0-922 London, England, Freedom of the City Admission Papers, 1681-1925

- ^ The Picture of London J Feltham

- ^ UK, Poll Books and Electoral Registers, 1538-1893

- ^^ Information courtesy of a Dent family member.

- ^ Bury and Norwich Post 2 June 1802

- ^ The National Archives of the UK; Kew, Surrey, England; General Register Office: Registers of Births, Marriages and Deaths surrendered to the Non-parochial Registers Commissions of 1837 and 1857; Class Number: RG 4; Piece Number: 306

- ^ The National Archives; Kew, England; Prerogative Court of Canterbury and Related Probate Jurisdictions: Will Registers; Class: PROB 11; Piece: 1444

- ^ see Bedfordshire Archives Service Catalogue; Receipts and Payments book made by Ed. Chapman on account with Wm. Dent Reference Z155/1

- ^ Northampton Mercury 23 November 1805

- ^ Northampton Mercury 08 April 1809

- ^ Northampton Mercury 08 October 1808

- ^ Records of London's Livery Companies Online Apprentices and Freemen 1400-1900 07/08/1810

- ^ Guildhall, St Sepulchre Holborn, Register of marriages, 1786 - 1802, P69/SEP/A/01/Ms 7222/4 London, England, Marriages and Banns, 1754-1921

- ^ see Holden's Triennial Directory for London 1805

- ^^ The life and letters of Edward John Dent, Chronometer Maker, and some account of his Successors, Vaudrey Mercer

- ^ The National Archives; Kew, England; Prerogative Court of Canterbury and Related Probate Jurisdictions: Will Registers; Class: PROB 11; Piece: 2172

- ^ see British Museum: Trade card in Heal Collection.